Yesterday, my borrowed computer took me into corners of the web which I hadn't discovered before. Yes, all on its own. It shifts, usually on to an advertisment, hands-free. Mostly, this is infuriating. But this time it was a joy. So I spent many hours amongst the on-line shops, related to ebay, revelling in old programmes and ephemera. And amongst a rather good lot of stuff, and a lot of ordinary, I found some items which to me are 'little treasures'. And one which is, to me, a wonderfully delicious treasure.

So here goes. To begin with, three items which should interest Australian historians. A rare breed, but I'm sure someone out there will like these ...

This is a bill for the little opera company which would, eventually grow into Australia's first important resident company. William Saurin Lyster manager for prima donna Rosalie Durand, baritone Fred Lyster (his brother), English vocalist Georgia Hodson, of the well known Hodson family of singers and musicians, and supporting players Frank Trevor and Ada King are all already in place ... although, once the company got itself a tenor, Miss Hodson wasn't obliged to play men all the time.

A little more than a year later, the 'New Orleans' had been dropped from the bills, and the tenor had arrived. As had the genuine prima donna, needed to allow the company to expand into a broader repertoire: Henry Squires and Lucy Escott would become the backbone of the Lyster company, Georgia could relax back into being a mezzo in skirts, and Rosalie got a few nights off. The English Stephen Leach and Signor [Alfred Pierre] Roncovieri (d San Francisco 20 November 1874) were California pick-ups for the San Francisco season, and did not become permanent members of the troupe.

The following year, the company sailed for Australia, and into a proud place in the history of down-under opera, of which story has been carefully told elsewhere. I have minutely tracked the lives and careers of Mrs Escott, Mr Squires and even Mr Leach, which articles (a little large for blogging?) are safe and sound in my Dropbox with the other 900 Victorian Vocalists.

Also of 'Australian interest' is this bill from a few years later. Billy Birch's Minstrel Company at the Eureka Hall. In between the minstrel acts, proven French opera diva Fannie Simonsen sings 'Casta Diva' and her husband gives a fiddle number. Separated by 'Sally, Come Up!'. I presume they didn't take part in the 'Chaw Roast Beef' walk-round!

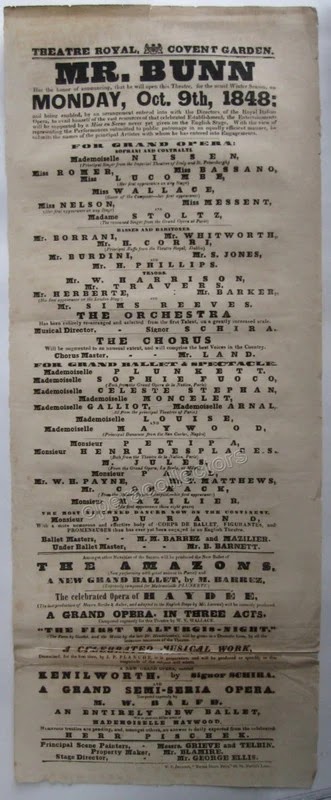

Leaving the west coast, and heading east, we come upon another, even earlier, and even more significant performance of The Bohemian Girl, given by a fledgeling company which was to become as important to Britain as the Lysters did to Australia.

This bill is from the 1855 tour of what was to become the famous Pyne and Harrison troupe -- Louisa Pyne (soprano) and William Harrison (tenor). Baritone Conrad Borrani (from Cheltenham), man-of-all-work Henry Horncastle and Louisa's sister, mezzo Susan Pyne, are there ... the rest are local 'extras' ... and the conductor is Thomas Comer, once of Bath, now of Boston. Verily, an historic playbill.

And so, back to England. A delightful programme for a private concert, given by contralto Annie Lascelles (Sarah Ann Cobb from Newark), at the home of the Marchioness of Downshire ..

The members of the Catherine Hayes concert party made up the bulk of the bill, but alas, without Miss Hayes, who had died shortly before. Mlle Guerrabella and Louisa Vinning filled the gap. I see that Annie sang ‘Di tanti palpiti’, ‘Effie’, ‘Les Souvenirs’, the Gazza ladra duet and ‘a new song’, ‘The Night Bird’ by Francesco Berger. The two ladies joined Tennant and Burdini in a rendition of the Polish National hymn to close the first part.

Thus says my biog on Miss Lascelles ... alas, the programme is so badly faded (and in pink ink!) as to be illegible.

But there is another private performance programme which excited me even more. It's not even a concert, it's family amateur dramatics in a family home. A home at an address which will mean nothing to anyone else in the world, I imagine, except me. Number 13 Hinde Street.

Hinde Street was a decidedly musical street -- Charlotte Dolby lived there -- but number 13 was the home of the Chubbs and the Messents. Who were, of course related by marriage. And Miss Sophia Messent, later to be the second wife of solicitor William Chubb (his first wife had been her sister, Emily's), was a Victorian Vocalist with a capital pair of Vs. Yes, of course, she's one of my 900, and I'm going to append my article here, for the benefit of those interested.

But first, who are all these folk above. Well, there's Sophia's brother, John Messent, who, I suspect, was the moving force behind this entertainment. He was hot for dramatics. Frank Edward and Philip Glynn are the sons of her other brother, Philip, the civil engineer, and would have been 9 and 11 years old. Amy Sophia Eliza (20), Lucy Blanche (19, 1854-1943), Emily Rose (18) and Willie Phillip St Leonards (15) are the children from William's first marriage, Charles Lyttelton Chubb (24, b 12 March 1850; d 15 April 1937) was the son of his brother, Thomas (1824-1888), and would later marry cousin Blanche, Arthur Bruce (17, 1857-1902) was another. One big happy family, from the days before television and other such passive entertainments. Lovely. That's why I like ephemera.

And here is the memorable Sophia.

MESSENT, Miss [MESSANT, Sophia Harriet] (b Haggerstone, Shoreditch, London 10 December 1823; d 47 Aldridge Road Villas, Westbourne Park, London 10 January 1903)

‘The linnet of linnets’, is how a critic described Miss Messent, at the height of her powers, in the early 1850s. One of the outstanding British sopranos of her time, she closed down a blossoming career on the operatic stage, at an early age, in favour of a voluminous and successful concert career, lasting for two decades.

Sophia Messent or Messant (the spelling seems to have varied from generation to generation) was born in London, the daughter of Phillip Messant (b Netherfield, Essex c 1792; d 13 Hinde Street 29 January 1858), a successful Soho corn chandler, and his wife Sarah Martha née Shickle (b North Walsham, Norfolk, c 1801; d 13 Hinde Street 30 January 1868), and followed her musical studies at the Royal Academy of Music, under James Bennett.

She began performing in public while still a student, making her first appearance singing a romance by Spohr, at a concert given by Mons Maggioni, at Golden Square in January 1842, alongside Bennett and Alicia Nunn. In July, she appeared in concert at the Royal Adelaide Gallery, this time in the company of fellow RAM students Charlotte Dolby and Louisa Bassano, Ernesta Grisi and … the Infant Sappho.

Miss Messent’s potential was quickly noticed. When she sang at Kennington in April 1843, alongside the Birch sisters and Miss Bassano, the critics wrote ‘another very promising aspirant for vocal honours… [she] has a clear and flexible soprano voice of considerable compass, power and sweetness ... [she] may achieve a brilliant career’.

Shortly after, Thomas Mollison Mudie gave a series of concerts, in which some of the Royal Academy’s outstanding pupils of recent years took part: once again it was the Misses Birch and Bassano, plus Marian Marshall and Sophia Messent, who sang the soprano and mezzo music. Miss Messent gave ‘Voi che sapete’ and Mudie’s own ‘Now the bright morning star’ and duetted with Miss Marshall (‘Ah! perdona’), and it was noted, even in such company, that she ‘showed indications of rapid improvement’. In early 1844, Mudie dedicated several songs and duets (‘There be none of beauty’s daughters’) to the 21 year-old soprano. ‘The lady is still a student in the profession of which she promises to become an ornament. Her voice is clear and her intonation firm and distinct’, enthused the press when she sang at Wolverhampton in March.

In early 1845, Miss Messent took part in Julius Benedict’s concert and in the premiere of a new Stabat Mater composed by Edward Fitzwilliam (15 March), and during the season she sang in an increasing number of London concerts. When she appeared at a Fête champêtre in Regents Park, alongside Julie Dorus-Gras and Eugénie Garcia, singing Sidney Nelson’s cavatina ‘The Forest Queen’, she was praised for her ‘great facility and taste’, when she repeated it at Signor Cittadini’s concert, she was voted ‘delightful’, but when she ventured an aria from Roberto Devereux at Josef Staudigl’s concert (25 June) The Musical World (no fan of Donizetti) delivered what might almost count as a gentle backhander: ‘We have heard no voice, for a long time, we think, so deliciously befitting the pathos of some of our old love songs’ .

It was a comment which, in one form or another, would follow Miss Messent around for the whole of her career. She could and did, throughout her life as a singer, sing the most florid of Italian arias with the ‘great facility and taste’ the same journal had already praised, but time and again, her greatest success would come in English music. In fact, just a few weeks after this review, she introduced an unpublished song by Linley at Master Rippon’s concert, and her performance was acclaimed as ‘the best specimen of ballad singing we have heard for a long time’.

Yet, days later, Miss Messent set out on a brief concert round teamed with Sra Brambilla and other artists from the Italian opera, in September she was singing at Mr Carte’s concert alongside Grisi and Mario, and alongside Charlotte Cushman in Guy Mannering at Manchester, in the new year she went out with another Carte party, this time led by Vincent Wallace, and featuring Sophia Schloss, during which she appeared as Margaretta in No Song, No Supper, Zerlina in Fra Diavolo and gave selections from the brand new Maritana, and, on 7 November, she made a first appearance at Exeter Hall, singing alongside Miss Rainforth in Israel in Egypt with the Sacred Harmonic Society. The following April, she partnered Susan Sunderland in Joshua, but although she appeared in oratorio, off and on, in the decades that followed, it never became a preponderant part of her work.

In May 1846, she would take also part in the final night of the venerable Concert of Ancient Music, alongside Caradori Allan, Thillon, Birch, Bassano and Pischek.

But, in 1846, she and her career largely went another way. She was engaged for the English opera season at Drury Lane, along with Anna Bishop, Emma Romer, Elizabeth Rainforth, Elizabeth Poole, and the Misses Collett and Rebecca Isaacs. The press took the liberty of assuming she had, like the last two ladies, been engaged as a ‘seconda donna’, and Miss Messent swiftly disabused them. She had been contracted as a ‘prima donna’. And she quickly proved it.

The old ballet-opera The Maid of Cashmere was remounted as a support piece to Anna Bishop’s revival of The Maid of Artois, and Miss Messent was cast in the leading role of Leila. She came through triumphantly: ‘a mezzo-soprano of delicious quality... she only requires experience to become a perfect artist’, wrote The Times. ‘A better first appearance we do not remember witnessing nor one more full of promise’, agreed the same Musical World who wanted her to sing ballads.

She went on to sing Agathe (Linda) in Der Freischütz with Stretton and King, under Mme Bishop’s Loretta, and seemed set to spend the season playing leads in supporting pieces when drama struck. Wallace’s new opera Matilda of Hungary, scheduled for production in February 1847, had to be postponed, and a fresh series of performances of Balfe’s The Bondman was hurried on to fill the gap. Although Emma Romer had created the leading role of Julie Corinne,the previous December, it was Sophia Messent who now went on opposite William Harrison, and ‘she displayed higher capabilities than any of which she had previously given evidence’.

On 5 April, Bunn produced at Drury Lane a spectacular based on Félicien David’s ‘ode-symphony’ entitled The Desert (or the Imam’s daughter), and Miss Messent was cast as the piece’s heroine the Princess Ipomayo. Alongside the spectacle, Sophia Messent was the star of the piece, with a cavatina, ‘Sweet Charity’ (‘she was very happy in the cavatine … much taste and feeling’), an aria, ‘Nearer as we approach’ (‘she was excellent in the aria…’) as well as ‘some exceedingly clever ballads by Mr Tully’, which were used as padding between the bits of Félicien David.

In April, she was cast as Elvira in Masaniello with Harrison, and when Benefit time came around at the end of the season she appeared in concert, ‘sang a Scotch ballad very tastefully’, and appeared as Rosetta in Love in a Village alongside Mr and Mrs and Mary Keeley.

In July she took a Benefit of her own, at the St James’s Theatre, and for the occasion she chose to portray Lucia di Lammermoor: ‘a marked improvement in both her acting and her singing since we saw her at Drury Lane..’On the same programme, her sister, Emily, made a debut as an actress, playing Juliana in The Honeymoon.

Alfred Bunn’s reign at Drury Lane having come temporarily to an end, the new season was being staged under the management of the conductor Jullien, who swiftly announced that he had put Miss Messent under contract and was sending her off to Paris to study with Manuel Garcia. His leading ladies for the season would be Julie Dorus-Gras, Charlott Ann Birch and Madame Leali (otherwise Susan Hobbs from Bath, who had already been given her Jullien-sponsored makeover by Garcia).

Quite how long Sophia Messent spent in Paris, and quite how long she studied with Garcia, I do not know. But I know she was back in England, although apparently sitting around Drury Lane idle while Mme Leali flopped egregiously, for on 9 February she was once again called upon to leap into a breach. The occasion was the Benefit of the new young tenor, Mr Sims Reeves, who had been the notable success of Jullien’s sometimes rather odd casting, and the opera was Lucia di Lammermoor, in which Reeves had been starring opposite Mme Dorus-Gras. But tonight the unpaid Mme Dorus-Gras couldn’t or wouldn’t play. The mezzo-soprano Helen Miran went on with the book for Act One, while Miss Messent was readied, and the young singer went on to complete the opera to dazzling effect. The following week, Lucia was repeated, with Miss Messent, this time, billed in the title-role alongside Reeves, and the press was ready. ‘Miss Messent […] who had now had the advantage of sufficient preparation, acquitted herself in a manner highly honourable to her talents and well deserved the great applause she received. Her performance, it is true, betrayed inexperience and immaturity of powers, but it gave promise, at the same time, of great future excellence. Her voice was always perfectly in tune, and beautifully pure and silvery in its tones, but was so deficient in fullness and volume, that the orchestra, when it played all forte, completely overpowered it … In the slow and sustained passages, when she had the time to form and utter her tones deliberately, they were rich and full-bodied, but this quality disappeared and the thinness and weakness returned whenever she had to execute a florid or rapid phrase… Miss Messent has refinement of style and sings with grace and feeling; she is possessed of that most essential requisite – beauty of person, an is gifted with intelligence and energy ... on the whole, Miss Messent will certainly prove a great acquisition to the musical stage.’ (Daily News)

Another week later, Jullien mounted his own Benefit. For the occasion he put up one act of The Marriage of Figaro, one act of The Maid of Honour (the season’s new opera) and finally one act of Lucia di Lammermoor with Sophia Messent in the title-role and Hector Berlioz at the baton. The whole thing was such a success (which was less than the season had been) that they played it again two nights later.

Sims Reeves, by the way, returned the favour. When Miss Messent mounted the first of what would be her many concerts over the years to come on 10 May 1848 at the Sussex Hall, she was able to bill the new tenor star banner-sized ‘Mr Sims Reeves’s first engagement in the city’ above Charlotte Dolby, Louisa Bassano, Miss Wallace, J P Goldberg and Burdini.

She appeared in concert through the season (‘Kathleen is gone’, ‘A lonely Arab maid’, Kalliwoda’s ‘Seest thou at even’, Curschmann’s ‘Maiden gay’, ‘Deh vieni’, ‘O, Maritana’) but Alfred Butt had now set up his stall at Covent Garden, and Miss Messent returned to the opera. But this time there were no incidents, and no chance for her to shine. When The Bondman was played, Emma Romer took her original role, and Miss Messent supported as Mme Jaloux (‘she sang and acted the trifling part with much care and talent’), when Miss Romer sang La Sonnambula, Miss Messent was Lisa (‘excellent’), and when Miss Emma Lucombe was given the title-role of Auber’s Haydée to play, Miss Messent was cast as Raffaela. On 6 December, Henri Laurent’s opera Quentin Durward was given its premiere, with William Harrison in its title-role, Borrani as the King, Mrs Donald King as Isabella and Miss Messent in the part of Princess Joan. She was encored in her sombre song ‘The merry dance is not for me’ on opening night, but Quentin Durward didn’t have too many other nights.

Her second operatic season with Alfred Bunn had, somehow, in spite of all her earlier success, been less satisfying than the first. Maybe she thought so, too, for Sophia Messent, after the close of the Covent Garden season of 1848-9, and a short season at Bath and Bristol with the Donald Kings – in which Mrs King sang Lucia and Zerlina, and Miss Messent No Song, No Supper, Lady Allcash and Gillian in The Quaker, billed as ‘seconda donna’ -- never again set foot on the operatic stage. But she more than compensated on the concert platform.

The list of Sophia Messent’s credits which I have accumulated – and it is, obviously, far from a comprehensive one, given that many concerts both private and public were neither advertised nor reviewed – stretches to eighteen pages. To list even a selection of them chronologically would serve no purpose, because there is no ‘development’: Miss Messent began her career as she ended it, she did not change direction, she did not branch out into new kinds of performance, she simply sang, week in week out, through twenty seasons, in the London and suburban concerts, and, less often, further afield.

By and large, she did not appear in the big ‘Italian’ concerts, in which the stars of the opera repeated their choice arias, nor did she make a speciality of sacred music – although, as I have said, she appeared at times with the Sacred Harmonic Society (Judas Maccabeus 1855) and London Sacred Harmonic Society (Messiah1854) at Exeter Hall, with the Harmonic Union in Elijah (1854), in Elijah with Jenny Lind (1855), in George Lake’s Daniel (1852), in oratorio at St Martin’s Hall (Creation with Santley’s debut, Messiah 1857, Messiah 1858), and she sang the part of Beauty in George Perry’s Benefit performance of the Handel pasticcio The Triumph of Time and Truth at Store Street Music Hall (February 1853).

Miss Messent was seen at the Hanover Square Rooms and St James’s Hall, at Exeter Hall and in the homes of the fashionable and aristocratic. She also sang in such venues as the Beaumont Institution, Whittington Club, the Sussex Hall, the Princess’s Concert Room, at the Surrey Gardens, the Crosby Hall, the Lowther Arcade, the London Tavern and in the city’s many Literary and Scientific Institutes. In fact, there can scarcely have been a London concert venue at which, during her career, Miss Messent did not sing. For she seemingly had no vanity. She would be up on the stage at the Hanover Square Rooms one day, sharing a programme with the cream of British vocalists, and the next day she would deliver the same music in some small, suburban venue alongside artists completely unknown to fame. And the fare which she delivered was that same mixture that she had delivered when she first went on the concert platform: a mixture of the classical and the operatic, and of English songs and ballads, ancient and modern.

Among the mass of her concert credits were included the first series of the Exeter Hall London Wednesday concerts in 1849 (‘Jock o’ Hazeldean’, Euryanthe quartet) in which she again took part in 1852 (‘Come out to me’, ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’) and 1853 (‘Tell me my heart’, ‘I dreamt I dwelt in marble halls’, ‘Ye spotted snakes’ with Grace Alleyne, ‘Se crudele’, ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’, ‘Softly sighs’)

She toured with various concert parties, including one with Sims Reeves and George Case in 1853 and another with Frederic Lablache, John Herberte and her pupil, Julie Mouat, then one under the Cramer and Beale management, with Clara Novello and Alexander Reichardt in 1855. She took part in the St Martin’s Hall Monday Evening concerts in 1857 and the Crystal Palace Saturday concerts (‘Tell me, my heart’, ‘Jock o’ Hazeldean’, ‘Deh vieni’, ‘We’re a nodding’, ‘Se crudele’ with Perren). She was seen at the Monday pops in 1859 and as late as 1863, and with the Vocal Association alongside Mme Lemmens Sherrington, Karl Formes, Marie Cruvelli, and Augusta Thomson.

And on top of this extremely busy schedule, Miss Messent, not only taught and gave classes at her home at 13 Hinde Street, but each year mounted a concert, and some times additional soirees of her own. That of 31 May 1849 (‘under the gracious patronage of her most gracious Majesty the Queen, His Royal Highness Prince Albert …’) included Pischek, Reeves, Mme Nissen, Burdini, Bodda, the Pyne sisters, Misses Bassano, Dolby and Wallace on its bill, and Sophia sang ‘Crudel perche’ with Reeves, the Matrimonio segreto trio, and three solos. At that of 6 June 1851 (with John Herberte) at the same venue, she featured Donizetti’s ‘Quel guardo il cavaliere’ (Don Pasquale) alongside Pischek, Miss Browne, Mlle Graumann and Miss Poole.

In 1852, on 21 April, she staged both a soiree musicale at her home, at which she introduced W H Grattan’s ‘Wearily, oh wearily’, and a matinee musicale (3l May) with Evelina Garcia, Annie Lascelles, Ursula Barclay, Reichardt, Bodda and Staudigl. In 1853 (21 June) her matinee musicale featured Sainton-Dolby, Lascelles, Gardoni, and Lefort, and Sophia duetted ‘Crudel perche' with Pischek and presented ‘Evening’ written by the Earl of Belfast. ‘[She is] now recognised as one of the most popular of our chamber vocalists’, quoth the press.

In 1854 (23 May) she returned to the Hanover Square Rooms and was welcomed by the critics: ‘None of our favourite vocalists surpass this young lady in those attractions which lend so signal an aid to vocal power – a graceful manner, and a cheerful and genial demeanour’, and repeated the following year (8 June 1855) in a joint presentation with Brinley Richards, singing a duet of his composition with Sainton-Dolby, plus the Torquato Tasso ‘Quando quell’ uom’, Linley’s ‘Laurette’ and Mori’s ‘Mind you that’. Richards and she joined together again, the next year at Willis’s Rooms (27 May 1856). This year’s new duet was ‘How beautiful is the night’ which she sang with ‘the new bass’, Mr Tillyard. Later she would sing it with another new bass: Mr Santley. ‘Miss Messent’s vocal performances were excellent and successful. She was especially happy in the scena from Ernaniwhich was most warmly applauded’ ‘One of the most agreeable of our native vocalists ...’

Vocalists of the repute of Clara Novello, Sainton Dolby, Santley, Reeves, Catherine Hayes, Gardoni and Viardot-Garcia featured in Miss Messent’s soirees and concerts (May 29 1857 soiree June 12 1857, 4 June 1858 (with Richards), 10 June 1859, 19 June 1860, 7 June 1861, 30 May 1862, 27 May 1863) always to a ‘very brilliant and fashionable audience’ ‘the room was crowded in every part’, always to splendid notices: ‘an able exponent of the Italian school [and] one of the best ballad singers we have’, ‘conspicuous for the purity of style, the feeling and the distinctness of enunciation which give her so high a place among out English ballad singers’.

The ballads weren’t quite all English, but very largely. Old and new. A small selection from those she gave in those years: J W Hobbs’s song ‘The Crier’ (‘Oh yes, oh yes, oh yes’) (‘it has been growing in favour ever since this syren adopted it at the Surrey Gardens’), Wallace’s ‘Why do I weep for thee’, Arthur Hyde Dendy’s ‘The Song of the Petrel’, Curschmann’s ‘Maiden gay’, Glover’s ‘Little Gipsy Jane’, Baker’s ‘I’ve a heart to exchange’, Linley’s ‘Kathleen is gone’, the famous ‘Tell me, my heart’, ‘They won’t let me go’, Kingsbury’s ‘The primrose is blooming again’, Gabriel’s ‘Regret thee’, Minima’s ‘O skylark’, ‘Comin’ thru the rye’, ‘My lodging is on the cold, cold ground’, ‘Kathleen Mavourneen’, Mellon’s ‘I arise from dreams of thee’, Neate’s ‘The little trout’, S W Waley’s ‘Lurline’, Mrs Carteright’s ‘A pilgrim’s rest’, ‘When sigh long suppressed’, Pelzer’s ‘Dinna forget, laddie’, ‘Come out, Lord of the castle’, ‘Fairyland’, Louise Christine’s ‘The Dreamer’s Solace’, ‘The song of the siren’, Freddie Clay’s ‘I have plighted my troth’, Lover’s ‘Jockey to the fair’ and any number of songs by Brinley Richards. Sophia and Elizabeth Poole premiered Glover’s successful duet ‘The Cousins’.

The operatic side of her repertoire included ‘Sombre forêt’ (William Tell), ‘Per pietà’, Ricci’s ‘Che dura vince’, ‘Deh vieni’, ‘Ah che morir’ (Tancredi) ‘Quando quell’ uom’ (Torquato Tasso), ‘Ernani involami’, ‘Ah! fors’è lui’, ‘Vieni, torna’ (Teseo), ‘The Power of Love’, ‘Deh per questo istante’ (Clemenza di Tito), ‘Sweet spirit, hear my prayer’(Lurline) and the duets ‘Dunque io son’ and ‘Tornami a dir’.

She was even to be heard in Jetty Treffz’s famous ‘Trab! trab!’ and duetting Fioravanti’s ‘The Singing Lesson’.

Throughout, she was received with delight. When she sang at the Westminster Institution with Miss Poole, Benson and Weiss the critic rhapsodised ‘and here is pretty Miss Messent with her cheeks full of dimples come to carry off the lion’s share of the laurels’; when she gave over her place at the Surrey Gardens to another soprano, the press sighed ‘we missed Miss Messent’s winged and dulcet notes that float on the lake like air borne sounds’.

At her 1860 concert at the Hanover Square Rooms, after her rendition of Mercadante’s ‘Ah! rammento a lui d’accanto’, of Franco Berger’s ‘Ask not why’ and ‘Twas within a mile of Edinboro’ Town’, the critic came back with a notice which was just like that of a decade earlier ‘Miss Messent sings simple ballads so prettily that it seems a pity she does not turn her attention more to them, and less to Italian bravuras which, although she masters them with sufficient ease, do not exhibit her talents to so much advantage’.

From 1864, Miss Messent appeared less on the concert bills of the nation, but when she appeared on 20 June 1866 at W T Wrighton’s concert, singing his song ‘Early Ties’, there was a difference in her billing. She was now ‘Madame Messent’. In fact, she wasn’t ‘Madame Messent’, she was Mrs Chubb.

In 1852, Sophia’s sister Emily [Sarah] Messent – who had become an actress at the Haymarket Theatre, the Queen’s Manchester et al – married William Chubb, a solicitor from Malmesbury, and a partner in the well-established law firm of Chubb, Deane and Chubb of 14 South Square, Grey’s Inn. She bore him four daughters and, finally, a son. The Chubb family lived at 13 Hinde Street (a most musical of streets, Charlotte Dolby was a neighbour), and with them, also, lived most of the members of the Messent family, including Emily’s parents, and sister Sophia.

At the age of thirty-three (27 September 1861), Emily died at Reigate, of a haemorrhage of the lungs, and two years later William Chubb married his sister-in-law, Sophia. Because of the law, then infamously current, against ‘marriage with deceased wife’s sister’, in vigour in Britain, the marriage took place in Neuchatel, Switzerland (18 July 1863).

After her marriage, Sophia only appeared a handful of times in public, and my last sighting of her on a platform is at Kennington in a Benefit concert in April 1867 with Louisa and Susan Pyne and Montem Smith. William Chubb died in 1885, his wife lived to the age of 79, and died in 1903.

As well as two sisters, Sophia Messent also had two brothers The elder, Philip, became an engineer in Tynemouth, the younger, John, became an actuary and secretary with the Briton, Medical and General Life Insurance Company, and a society gentleman. He also took part in amateur dramatics and operatics, and in 1854, he can be seen performing at the St James’s Theatre as a Macbeth witch and as Robin in The Waterman with William and Harriet Tennent.

2 comments:

I loved reading this - thank you so much for sharing. I was looking for Sophia because I could see she was listed in the 1851 census as a artist and I wondered what sort of art she had produced. Your blog gave me so much information and also information about her brother John who was the real reason I was looking at the census. I work for the archive at Aviva and his company, Briton Medical and General is one of our ancestor companies. It was great to read about the artistic side to him especially as all I knew was that he had risen to be company secretary very young and was implicated, after his death, in the loss of over £100,000 of the company's funds!

Splendid! They were quite a family ... my article on Sophia is included in my book (2017) VICTORIAN VOCALISTS ... so Aviva has a connecion to one of the best English sopranos of her era. Delighted to have filled in some background for you. Thats what I do this for :-)

Post a Comment