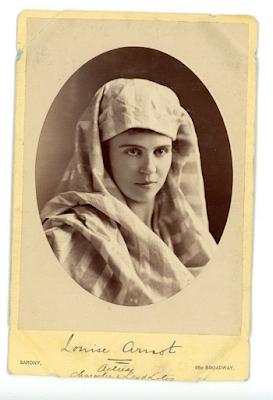

NIKITA, Mlle [NICHOLSON, Margaret Louise Putnam] (b Washington, DC 18 August 1872; d unknown)

Many Victorian singers, and particularly some of those from the left hand side of the Atlantic Ocean, suffered sadly from being ridiculously over-hyped by their entourage, their managers and, on occasion, themselves, but it is hard to think of one other who was rendered quite so foolish by such posturings, pretences and pretensions as ‘Mademoiselle Nikita’.

Unjustifiably over-publicised in her life and not lengthy career, she nevertheless survived into a number of books of reference, where the descriptions of that life and that career reek decidedly and obviously of the publicity pages. One of the most amazing of these semi-ficticious articles is that in the respected Baker’s Dictionary, where the lady is credited with a whole line of operatic performances which she never played. Otherwise, she is said to have been born in Philadelphia, or was it Virginia…?

Ah, Virginia. The Virginia story is the first and most fatally ghastly piece of all the fakery that would surround ‘Nikita’. Quite who invented it and when, I have yet to discover, but it seems to have gone with the cutesy name, which I first spot when the young lady was launched on Europe, under the aegis of Moritz Strakosch, at the age of 14 years and 8 months.

‘Mlle Nikita’, born in Virginia, got carried off by marauding Indians, at Niagara, when just a tiny tot. She was brought up by the Indians, and only returned to her mother, at the age of 10, when the tribe’s big chief, Nikita, died. Alas, her father had died, not knowing that his babe would ever come home…

Robert Joseph Nicholson, from Maryland, formerly a brass-moulder, but latterly a prison warder in Washington DC, would certainly have been surprised to hear that he was dead, also that he had not supported little Maggie (along with her brothers and sister) through her childhood without the help of a tribe of Indians.

However, someone, somewhere, was daft enough to think that this fairytale – splashed over half a column of paid advertising when the moppet first showed her little head in London – would ever be believed by any but the most gullible. One paper snorted ‘they must have a very good Conservatoire on the Niagara reservation’. Had she had no talent at all, Nikita would have been a bad joke of Florence Foster Jenkins proportions. The pity of it was, she was – at least to start with -- a competent vocalist and – of course – as a pretty child prodigy, she had her attractions. But, to those who weren’t gulled by the stories, she was dragged up as something of a silly freak show.

Once Maggie Nicholson gave up the Indian story (which would never, sadly for her, ever be forgotten), she gave a different version of the ‘facts’ of her early days which, for all that it was still pretty gushing, had a little more verisimilitude to it. But there were two things that never changed. Her age and her date of birth. They didn’t have to, for Maggie was a genuine child performer, born in 1872, and she never had to lie about her age. There she is, in the 1880 census of Washington, with her m

The new story went that Renie or Benie had been taking singing lessons from an uncle, a Mr Le Roy, and little Maggie had supplied the high note that her sister could not reach. Mr Le Roy promptly put her into training, and also into concert, taking her on the road in New England, aged twelve, as ‘The miniature Patti, Louise Marguerite the wonderful child singer and actress’.

The ultimate result was that, on 16 December 1885, with the backing of a group of New York ladies, Mrs Sarah Rebecca Nicholson and 13 year-old Maggie set sail for Europe. In Paris, Maggie was taken under the wing of Herr Moritz Strakosch, all haloed still, a quarter of a century on, with his ‘discovery’ (if not necessarily his teaching) of Adelina Patti, and now, somewhat foolishly, famed as a finder of great talent.

Strakosch introduced Maggie – now yclept ‘Nikita’ and equipped with her Indian story – at Nice, in April 1887, on the occasion of a charity concert for the sufferers by the recent earthquake. The local music critic was suitably sceptical of ‘le dernier astre découvert par M Strakosch’, and even more sceptical of the foolish publicity, but he liked Maggie, and was particularly impressed that, given the stable she came out of, she was not put up to sing lashings of roulades and coloratura, but instead gave simple renditions of ‘Connais-tu le pays’, ‘Deh vieni non tardar’, Giordani’s ‘O sanctissima vergine’ and a piece of Lohengrin (‘Wagner? We did not know the Indians were so up to date’): ‘La voix de cet enfant de 14 ans, bien que complètement formée, prendra encore de la force certainement, mais le timbre en est déjà si pur, si frais, il y a tant de charme dans sa manière de phraser, tant de hardiesse dans son expression quand elle lance sa note au publique, comme si elle le jetait un bouquet de fleurs ..’

The try-out satisfactorily accomplished, Nikita was taken to London, and there, on 20 August, she made another debut, at Arditi’s Her Majesty’s Theatre Proms. This was an occasion for the embarrassing four-paragraph advertisement referred to above (Times) and there was, of course, a nice quote from Adelina Patti to the effect ‘My child at your age I could not sing as you do…’.

It was tempting fate. Reynolds Magazine shot back, after opening night, ‘In one sense this was true. Mme Patti, we believe, to have saved her life, could not have sung as Mlle Nikita does, but if the diva meant the expression of her opinion to be flattering... The newcomer may have a very wonderful history but her voice is an ordinary one ...’

The Times referred to ‘the ridiculous cock and bull story’ it had printed and pursed that she ‘still has some of the rudiments of her art to learn’ but, behind all the fuss, noted an attractive and very youthful appearance and a small, but not disagreeable, voice ... intelligent phrasing and perfect production …’

Nikita was kept on the bills (to some expressed surprise in some quarters), braving appearances alongside such as Clarice Sinico, and featuring, alongside ‘Batti batti’, ‘The Last Rose of Summer’ and a slice of Salvator Rosa, a run of Arditi songs: ‘L’Estasi’, ‘Fior di Margherita’ (‘The Daisy’ ‘sung with great success by..’), ‘The International Song’.

From London, she continued on to Paris. Her entourage had not taken the hint about the advertisements, and brochures were issued in advance telling the tale of her life with the Indians: ‘une reclame echevelée digne du grand Barnum avait essayé de nous la presenter comme la merveille des merveilles’ ... ‘la fée de Niagara’.. ‘ As a result ‘The public came with a bit of scepticism and a bit for a joke, and was agreeably surprised ... [she is] not a huge talent but has an agreeable voice and a way of singing that is a little cute but sometimes exquisite’. ‘Il y a peut-être chez cette petite sauvage l’étoile d’une grande artiste…’.

If there were, it would soon be extinguished. And Moritz Strakosch died.

Accompanied by lashings of publicity and advertisement ‘die neueste Wundermädchen’ went next into Germany (Berlin Singakademie 12 October 1887, Hamburg, Leipzig 25 November) and, under the aegis of Alfred Fischoff, Austria. Herr Fischoff got the Red Indian tale into the press all round Europe, along with Maggie’s portrait, as ‘Moritz Strakosch’s last pupil’ delivered her ‘Elsa’s Dream’ round Europe. The publicity claimed London, Berlin, Hamburg, Lübeck, Bremen, Hannover, Magdeburg, Leipzig, Dresden, Wiesbaden, Düsseldorf, Brussels. And why not? The columnists leaped gratefully upon the Nikita-train for colourful copy, and when they referred to the ‘neuste Gesangswunder’ it was for the reader to decide whether their tongues were in their cheeks or not.

In spite of the fact that Mapleson had announced that he would be hiring the ‘Gesangswunder’ for Zerlina and Cherubino for the coming London opera season, when she turned up again in London it was for more concerts, this time at the Albert Hall. And the ‘wonder child’/’huge success’ publicity was beginning to show signs of baffling even some who ought to have known better.

On her 1 March 1888 reappearance, she was large billed – ahead of such artists as Janet Patey, Mary Davies, Edward Lloyd and James Sauvage – and her rendition of ‘Deh vieni’, ‘Home Sweet Home’ and ‘I Dreamt I dwelt in marble halls’ was ‘warmly applauded’. The Times, who decided ‘she returns to London much improved in voice and in manner of delivery’, devoted the entirety of its review to her.

She followed up – sharing the big billing with Sims Reeves, and with Patey, Sterling, Lloyd and Santley amongst the alsos – in further concerts at the Albert Hall (Eckert’s ‘Echo Song’, ‘Voi che sapete’, Braga’s Serenata, ‘Aubade française’ by de Nevers. ‘Jewel Song’, ‘Batti, batti’), and then at St James’s Hall, and in August she was featured at Freeman Thomas’s Covent Garden Proms. ‘She is singing everywhere and coining money...’ reported the papers back home.

She returned to Europe (I spot a ‘Nikita-Konzert’ in Brussels in December) and, in early 1889, the Nikita outfit headed for Russia. Reports oozed back of sensational triumphs for ‘die vielgenannte Sängerin’ in ‘her stage debut’ in opera in Moscow (Zerlina, 22 March) and in concert in Odessa. The New York Times printed a (translated?) notice of one such: ‘(March 16) dateline Odessa ‘No singer has, in my recollection, so entirely captivated the musical public of this city, which is at all times somewhat severely critical of the claims of foreign prime donne, as the youthful and gifted American singer, Mlle Nikita…’ The Musical Courier printed another and different one: ‘Nikita, the soprano singer, made a very poor impression’.

She gave Dion Giovanni another whirl at the Deutsches Theater in Prague, and apparently added Fra Diavolo and Cherubino to her operatic register, but by May, she was back in London where on the 19th of the month she presented her own concert (‘her reappearance after her triumphant success on the Continent’) at St James’s Hall. The Era found her ‘Ernani involami’ was given ‘with great command of vocal resources and with excellent tone and style. The florid passages required a little more finish, but the command of execution was great, and the general rendering gave promise of Nikita becoming ere long a more effective vocalist still’. But the Nikita bandwagon were still overdoing it. The floral tributes that crowded the stage during the evening were way over the top, ‘All ‘the flowers that bloom in the spring’ will not make a great singer, but a good voice and musical sensibility will and, as Nikita has these qualifications, there is no doubt that she will do well, and be popular with the musical public’.

The Times however, was not to be hornswoggled. When she moved on to the Albert Hall, where another youngish vocalist was currently singing, they wrote: ‘A miniature edition of the Cuzzoni-Faustina warfare is, it would appear, being waged at the Albert Hall, where the claims of two young sopranos are hotly contested at certain concerts of a not very high order. Although neither has reached maturity of style, the voice of ‘Nikita’ – the omission of the ordinary prefix is one of the young lady’s lesser affectations – shows distinct signs of wear, such are caused inevitably by the tremolo in which she indulges almost perpetually. She compares unfavourably with Miss Josephine Simon whose voice is rich, sympathetic and remarkably even throughout its compass, and whose style is entirely unaffected…’

When she sang at Otto Hengler’s October concert, the press reported ‘She sang the everlasting ‘Ernani involami’ by Verdi, most notable for her faulty Italian pronunciation and the way in which she took her breaths’.

But it wasn’t just the British press. The Musikalisches Wochenblatt devoted half a column by its Odessa correspondence deprecating ‘die Trompetenfanfaren der Reclame’ around the singer. ‘After such publicity’ it ended ‘we expected a second Patti, and Fräulein Nikita certainly isn’t that!’.

But she continued her rounds: Leipzig, New Deutsches Theater in Prague (‘Ernani Involami’, Echo song, Roméo et Juliette waltz song), 16 November at Brauns Hotel, Lemberg, Dresden, 21 November 1889, at Vienna’s Bösendorfer Salon, Olmütz, in the company of pianist Arthur Friedheim and the cellist Eduard Rosé.

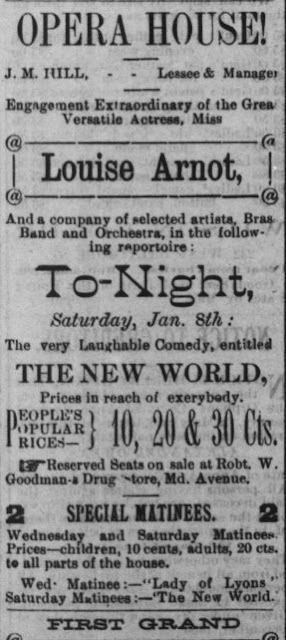

Much of the next year or two were spent ‘touring in Russia’, with time out to appear as Juliet in Roméo et Juliette at Warsaw and in 1890 she went to Coburg after which she began advertising herself as ‘Court Singer to the Duke of Coburg-Gotha’. She played a short tour in the British provinces – the

Belfast Philharmonic Society announced her coming in vast lettering (equal to Patti and above Patey and Titiens) as ‘the prima donna whose career has been one of the most extraordinary series of triumphs ever known’ -- and the Duke was shoved off her posters by the announcement that she was to be married to Prince Mirza Riza Khan, aide de camp to the Shah of Persia. Unfortunately, there were only two gentlemen of that name current in Persian court circles and both were married. The French press promptly pointed this out. Perhaps she was intending to point to Prince Malcom Khan of Holland Park, but he was married too.

During 1890 she travelled round Germany with the pianist Georg Liebling, giving her Ernani and Roméo and Juliette arias to cities and towns and spas on the usual bursts of publicity. Which didn’t stop the less susceptible critics from noticing ‘die Incorrectheit des Trillers und eine kleine Unebenheiten in der Colorature’. Back in Britain, the Nikita interviews and the Nikita quotes turned up regularly: ‘having completed her Continental tournée she has gone to Paris to meet M Gounod to study Marguerite and Juliette for her debut at the Paris opera next spring…’ and hey ho.

In December 1891 she is in Moscow, in April 1892 I spot her in Amsterdam, in December 1892 she advertised in the London Times that she was singing in Faust at Kiev. Russia, Chicago, Manchester… but not the Paris Opéra.

In fact, she got her greatest publicity when, having accepted an engagement to appear at the Trocadero in Chicago, for Dr Ziegfeld, according to the press, for the nice round sum of $50,000, she and her mother caused such trouble and put on such airs about ‘singing in a beer hall’, that the manager told her some home truths. Miss Nicholson loudly sued him for impugnations of intemperance and for suggesting that she had ever ‘sung in a beer hall’. Ziegfeld assured the press that it was all publicity, but she didn’t sing.

She headed back to Russia and central Europe, now billed as ‘Die amerikanische Nachtigall’, fulfilled a concert tour with the pianist Harold Bauer and – the Persian Prince having been exploded – again began being ‘cantatrice de la cour du Duc de Saxe-Gotha’. The press had a good laugh at that one. But, alas, good singer or not – and Russia seemed to like her - ads in the Times informed Britain that she was singing Romeo and Juliette, Mignon and Faust at Warsaw – that was what Nikita had become. A good laugh. She could be nothing else. Alas, her next claim was that she was ‘a direct descendant of Daniel Boone’.

Ultimately, in 1894, at the end of the indentures which she had signed with Strakosch and his heirs, Maggie Nikita did get to the Parisian stage. It was not, however, the Paris Opéra, nor indeed the Italiens, but the Opéra-Comique. Allegedly, she was signed for three years, and she hastened into print with a long list of the leading roles she was going to play. She didn’t. She also hastened into print with a paragraph telling how Ambroise Thomas said she was the only singer who could correctly deliver the finale of his Mignon.

It was, in fact, as Mignon that Mlle Nikita (‘a direct descendant of Daniel Boone’ ‘$200,000 of diamonds’, 104 concerts at the Word’s Fair’, ‘déjà célèbre dans les deux mondes…’) made her appearance at the Opéra-Comique on 15 October 1894, alongside Mons Féraud. The earth didn’t end. Or open. Le Ménestral said she was pretty, that her upper voice was good if peculiar, and the middle fair. But that she approached all her notes from underneath which was deeply unpleasant. All in all, she was just another soprano, with no special qualities. Noel and Stoullig, the ultimate chroniqueurs of the Parisian theatre, referred to her as ‘une jeune et brune Américaine qui a désiré faire consacrer par les Parisiens une réputation ...’

At the same time, the American press reported ‘They think they have found a phenomenal tenor in the brother of Miss Nikita, the young woman whose brief America tour accomplished more circus than the tour of a regular prima donna. All the advertising about her being stolen by Indians and Turks and having champagne sent to her rooms and fighting with her managers did not give her the prestige to which she might seem to be entitled, and now she has discovered a brother…’.

Mr M Le Roy (‘35 Avenue Macmahon, Paris’ ‘successor of Maurice Strakosch’), who had resumed the control of the Nikita operation once the Strakosches were out of the picture, led her off to Russia. She would return, he said, to play Lakmé in the new season. Well, she played Lakmé all right, but not in Paris. She played in it Riga. And Mignon at Mannheim. But she was back at the Opéra-Comique in 1895, and the Paris music press was not impressed: ‘Mlle Charlotte Wynn se voit sacrifiée à une Polonaise vaguement Allemande de mérite indécouvrable, de valeur pour tous mysterieuse, et denommé Mlle Nikita…’, ‘Les journaux annnocaient la rentrée de Mlle Nikita dans Mignon. Et en effet Mlle Nikita est rentrée. Faut-il s’en feliciter? Mlle Nikita nous a à peine paru supportable’.

Ouch.

But the announcements continued to come ‘Ambroise Thomas’s ideal Mignon’, it was reported, was being coached by the susceptible Massenet in the role of Anita in La Navarraise ... he was begging her to sing his Manon… she was to star at Mapleson’s new London opera house …

She didn’t. She did visit Britain and, there, joined Mr Harrison of Birmingham for a concert tour. Birmingham apparently hadn’t heard her before. Just, like the whole world, heard ‘of’ her. On her first appearance, she shared the platform with Margaret McIntyre – Miss McIntyre was met with ‘acclaim’, Nikita with ‘disappointment was felt in the direction of voice quality’.

But on it went. ‘Mlle Nikita speaks and writes no less than seven languages; is an excellent portrait painter, a talented pianist, a regular contributor to the literary page of the (undecipherable) of Vienna, a first-rate billiard-player, and a daring bicyclist. She has never tasted champagne nor smoked a cigarette …’ More Kings, more Daniel Boone … ‘far superior to Melba ….’

Maggie Nicholson was now 24 years of age. Her career (give or take Russia?) does not appear to have been the success expected and announced. You can’t fool all of the people. But it seems here and now to have ended. It is not that she disappears, far from it. She just doesn’t seem to sing any more.

One website which I have passed by says that she damaged her throat in a bicycling accident. That sounds a bit like the Red Indian saga, but who knows? Maybe it is true. I still see her, in 1898, proposing a tour of the German spa towns with Moritz Mayer-Mahr (piano).

Did mother die? No, she didn’t. Did Mr Le Roy die? Who knows? What I know did happen, is that Maggie Nicholson got married. But I don’t believe for a moment that that marriage ended her career. She didn’t marry a Prince or a Czar or an Indian chief, she married a gentleman by name James O’Hara Murray (d 1 February 1943), an engineer as young as she, who hailed from Demerera, Georgetown, in the West Indies. The marriage, which took place in London in 1898, was apparently a short-lived one. Which was foolish of Maggie, because Mr Murray went on to be a very successful businessman (J O’Hara Murray and Company, contracting engineers, Hatton Garden), with another wife (née Hylda Constance Blendel), and a truly top-class tennis player. He lived latterly in my favourite little village of Niton, Isle of Wight.

Where Nikita lived, I can’t be sure. She remained an American citizen, so thanks to the US passport office we can follow her around a bit. In 1897, when she’s supposed to be bicycling (‘a bicycling accident in 1897 crushed her throat and ended her career’), she is in Paris. In 1899 she is ‘living in Berlin’ and comes to America to visit her dying stepfather. Good heavens, Sarah Rebecca was getting through husbands fast. In 1900 it is still Berlin, and still in the company of Mr Murray (‘Mrs Nikita-Murray’), but – surprise – in 1915, she bills herself as of 80 West 40th Street, NYC. When she applied for a passport in 1918 she chopped five years off her age. You would think they could have checked, even in the pre-computer age. In 1921, she says that she has lived in France since 1895. Yet previously she had admitted only 1912-1918. And her reason for going to France in 1919 was to ‘marry a Frenchman’. Perhaps she wasn’t meaning a specific Frenchman, just any one… but she did. In the pages of the Brooklyn Eagle for 18 April 1923 I find the announcement of her marriage to Georges Masdusheil (?) de Colange ‘a French manufacturer belonging to an ancient Norman family’. Of course. ‘About thirty years ago [she] had a brilliant career in grand opera in Paris, Berlin, St Petersburg and Vienna’. And the American papers parroted ‘A Frenchman named Georges Masdusheil de Colange has married an American girl who is a direct descendant of Daniel Boone’. Sigh.

I’d find the story of ‘Nikita’ Nicholson rather sad, were it not that it seems that she was, at least, more than partly to blame for her own ridiculous image. But at least it seems that she had a happy ending. M et Mme George de Colange can been seen on the social pages of the 1920s (‘M le Roi de Suède honorait de sa présence, à Monte-Carlo, un grand déjeuner donné par Mme Georges de Colange’), and I imagine that’s them in Cisai-St-Aubin in the ‘thirties, breeding prize cattle and pekinese dogs. And, heavens, there she is in 1944 suing the US Customs for charging her duty on her late husband’s diamond (!) ring ‘worn by his widow since his death’. And again, 1950, Louise de Colange of 62 West 58th Street, sailing out of New York on the Queen Elizabeth …

And, so … could she sing?

Well, she has left to posterity a cylinder recording of the Mad Scene from Lucia di Lammermoor ... it seems it’s not bad. But it has probably got a purple label with sequins on it.

Just for the record, she was apparently claimed as a sometime pupil by Clarice Ziska of Paris.

Another record is found in Grove: ‘studied in Paris, won renown in Germany and in 1894 became a leading singer at the Opéra in Paris’. Oh dear, if you tell lies long and loud enough, like the frog-prince, they metamorphose into ‘fact’. Shame on you, Mr Grove.