One of the forgotten pioneers of American primadonnadom ...

VAN ZANDT, Jennie (aka VANZINI) [née BLITZ, Jane Newcombe Amelia] (b Brooklyn, 1 January 1836; d Paris 25 September 1913)

Jennie van Zandt from Brooklyn was one of the avant garde little group of American sopranos who made a significant international (in other words, at least partly European) career in the world of Italian opera the middle years of the nineteenth century.

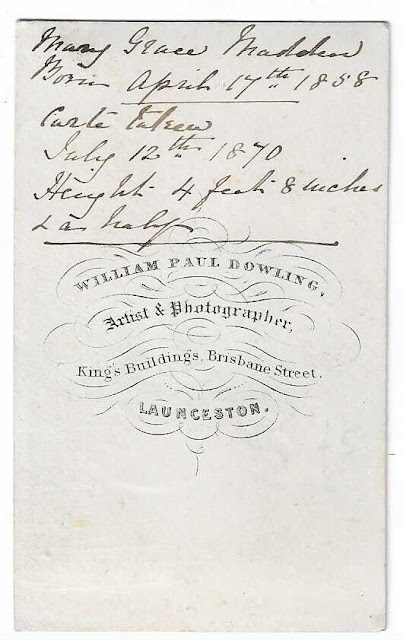

Jennie was apparently born in 1836 (‘definitive’ dates ranging up to 1845 have been given, and on her passport application she says ‘1839’), the third of the seven children of Antonio Blitz (b Deal, Kent, 21 June 1810; d Philadelphia, 28 January 1877), an English Jew, and his first wife, Maria Georgina Morris (m Lanarkshire, 27 November 1831), an Irish Scotswoman.

Antonio Blitz was something of a celebrity, one of the best known of contemporary magicians and ventriloquists (and not to be confused with those other professionals who took and traded on his name), initially in Britain but, from 1834, definitively in America. ‘Signor Blitz invented many of the famous tricks which still delight and surprise audiences at shows of legerdemain’ wrote an obituarist ‘The sphinx, the sack of eggs and the wonderful automaton trumpets were creatures of his inventive skill’.

The family is listed in Brooklyn in the 1850 census of America, where Blitz gives his age correctly but his birthplace as Germany, and his children as John (17), William (16), Jane (14), Ada (12), Arthur (7), Theodore (4) and Maria (2). Jane is also listed at a school in Jamaica, NY, where she is said to be 15. So it’s patently evident that she was not born in 1845 or 1839.

Blitz’s autobiography is published under the title Fifty Years in the Magic Circle.

Jennie began her professional career a little later than some, and not until she was already a married woman and a mother. Her husband was James Rose van Zandt (b Westchester, 1 October 1835; d Muhlenberg Hospital, Plainfield, NJ, December 1907) ‘cousin of ex-governor van Zandt of Rhode Island’, son of the worthy Robert Benson van Zandt (d Flushing, 3 August 1844) and his wife Mary Lawrence née Hicks, and a descendant of Wynant van Zandt, of Flushing and Douglastown, NY, the historic epicentre of the family of van Zandt. The couple were apparently wed in New York on 12 June 1855.

There would be four children born of the marriage: one son, Dudley A[ntonio] who gave his birthdate as 1 January 1858, and three daughters: Amelia ‘born 1855’, Catherine A (b 1863?), and Marie or Maria, who filled in her passport application ‘b Brooklyn 8 October 1863’, and is quoted in learned volumes as born on the same day in 1858 (which fits awkwardly with Dudley’s date), in Foyers et coulisses as 1861, but is listed alongside 13 year-old Amelia, in the 1871 census of Britain (as pupils at Duke House School, Leamington) as nine years of age.

Jennie van Zandt comes before my eyes for the first time as a vocalist on 27 May 1862, on the occasion of a concert given by the pupils of Antonio Barili’s newly-established Academy of Music (4 December 1861) at Dodsworth’s Hall. She took part in a piano trio, and then she sang. ‘Her first effort was the cavatina ‘Mi la sola’ from Beatrice di Tenda, her execution of which satisfied us that, if not yet an artist, there was in her nature the makings of a fine artist. She has a voice of rare beauty, pure and singularly sympathetic in its quality, and of that elasticity which renders execution facile without effort. Combined with this, she displays an earnestness and depth of passion but seldom seen ... and capable of the highest degree of cultivation. There was but little of the amateur to be observed in her singing ... one of the most promising vocalists we have heard for some time’.

Mr van Zandt, who was also to have sung, had a hoarse throat and scratched. We do not again hear of him as a vocalist.

On 22 Dec 1862, Jennie lined up again with Barili’s other prize pupils -- Mrs Charles Farnham, Mrs Eisenwein and the Misses Schwarzwälder -- but in the next exhibition (in which the future reciter and opera contralto Louisa Myers was included) it was Mrs Farnham who got to sing ‘Qui la voce’ and grabbed the notices!

Jennie made her debut as a concert singer in the late part of 1863, in Brooklyn. The first occasion I have exhumed (and it is referred to as ‘her first appearance before the public’ or later ‘a Brooklyn audience’) is ‘Her First Grand Concert’ given on 4 November at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, under her own auspices as Mrs van Zandt, ‘daughter of Signor Blitz’. The big name on he bill is that of Elena Angri, the celebrated wife of her new singing teacher, Pedro Abella, and the young William Castle also sang. Abella conducted, S B Mills played piano and a Signor Yppolito was the baritone de service. Tickets one dollar.

The Brooklyn Eagle reported the next day ‘a great triumph’ ‘The programme included a choice selection of operatic gems, admirably rendered throughout, especially the part assigned to the bright-eyed debutante of the evening...’. Jennie began with the duo from I Masnadieri with William Castle ‘the reception of the lady being such as to afford her hearty satisfaction’ ‘She not only delighted her audience but astonished them with the volume and sweetness as well as the brilliancy and purity of her voice. Especially was this noticeable in her truly artistic rendition of the popular scena from Traviata and the charming aria called forth by the enthusiastic encore she received. In the duo with Mme d’Angri, too, which was likewise encored, she charmed all with her admirable vocalism … In every way she justified the predictions of her most enthusiastic friends ..’

She was swiftly taken up by concert givers. On 29 December I spot her with d’Angri and Abella at a Regimental Band concert at the Academy of Music, and in January she appeared with the Brooklyn Philharmonic Society (‘Oh! mie fedeli’ Beatrice di Tenda, ‘Quanto amore’ with Centemiri): ‘It would be difficult to listen to the singing of this lady unmoved to admiration .. Brooklyn will never blush for having given birth to so fair and so accomplished a daughter’ sighed Brooklyn’s press.

In February she took part with Castle and Sher Campbell in a ‘Grand Promenade Concert’ at the Academy of Music and I also spot her, billed simply as ‘Mrs van Zandt’, singing at New York’s Dodsworth’s Hall (8 February 1864, ‘the lady sang with considerable brilliancy Bellini’s ‘Qui la voce’, the Venzano waltz and a plaintive local composition by [Alfred H] Pease’).

Operatic impresario Max Maretzek had been quick to move, and before the end of the year he had added the new Brooklyn soprano to his ranks, alongside the impressive Carlotta Carozzi Zucchi and his other American prima donna, Clara Louise Kellogg. As the time for her debut loomed, a New York paper wrote ‘The opera has had emphatically a week of triumphs. Carrozzi Zucchi has achieved a success that will not be soon forgotten in Poliuto ... through the week we are to have Don Giovanni with Miss Kellogg and Mrs Jennie van Zandt, a new candidate for operatic honours as Gilda in Rigoletto…’

It was 4 November 1864, a year almost to the day since that concert debut in Brooklyn, that Jennie stepped on to the operatic stage for the first time, and soon the word went round the papers of the country: ‘Miss Jennie van Zandt, for some time a successful choir and concert singer in New York, made her debut in Italian opera at the [New York] Academy of Music on Friday night in Rigoletto, the same part taken by Miss Kellogg on her first appearance. Mrs van Zandt made a very favourable impression on the audience and her voice is described as a clear soprano of good compass. She has been preparing for opera for the past fourteen months...’

On 19 November, Maretzek took his troupe up to Brooklyn, and Jennie repeated her Rigoletto alongside Massimiliani, Bellini and Kate Morensi, and Brooklyn’s music writer whispered a secret: ‘the circumstances under which this lady was induced to adopt the musical profession and turn her fine natural abilities to account have awakened a sympathetic interest in her behalf…’. Was it true? Mr van Zandt was, it seems, not a ball of fire, so maybe the family was indeed in need of money. But this excuse for the ‘unladylike’ pursuance of an artistic career was too frequent a tune in Victorian years to be readily believed.

In Brooklyn, ‘it was Mrs van Zandt, rather than the opera, that was the attraction’ and she did not let her home town down. ‘A more effective and agreeable performance could not be desired ... she aroused a tempest of applause’.

Back in town she was the soloist at Theodore Thomas's Second Symphonic Soirée (7 January 1865) as the Maretzek season at the Academy of Music ran on, and Jennie gave her first Lucia di Lammermoor, with Massimiliani and Bellini ('she sang better than we have ever before heard her').

On 19 January 1865, Mrs van Zandt made her first operatic appearance in Boston, playing Lucia di Lammermoor. The local critic echoed his New York brethren: 'Her person is petite, and her roles will naturally lie in the lighter operas. Her voice is sweet, sure and extensive in compass, taking middle C with fullness and touching the fancy notes in alt clearly and delicately. It is not strong, but has considerable solidity and much sympathy of tone. Her execution is very free and distinct and her trill exceedingly well defined. Her style is simple but of good method and she sustains evenly and without any tremolando. In action she shows the novice and at times her evident anxiety to sustain herself through the ordeal of the opera detracted from her singing which became constrained as she became too self-conscious. But she pleased the people and satisfied the expectations of the cognoscenti and she may be assured that having made a good beginning she has but to follow it up faithfully to be a favourite in Boston...’

Mrs van Zandt would soon go on to be a favourite well beyond Boston.

Having been slow to start her career, Jennie van Zandt now moved forward with considerable speed, soon challenging the younger Clara Louise Kellogg, already well established as an operatic prima donna, at the forefront of America sopranos, before setting out across the Atlantic to take on larger challenges.

In October 1865, Jennie left Brooklyn for Europe to ‘study with Lamperti’. Evidently, a lengthy period of study was not needed for, in months, Francesco Lamperti had done what he was best at and had placed Mrs van Zandt firmly in the tentacles of the most powerful operatic agent and casting director of the time, Bartolomeo Merelli.

Within weeks, Jennie was booked for her European debut at the Copenhagen Opera House,

Copenhagen wrote to the Parisian paper La Comédie: ‘C’est de l’Amérique que nous arrive Mlle Vanzini et Mlle Morensi, deux bijoux appelés bientôt a briller d’un radieux éclat sur les grandes scenes de l’Europe. Mlle Vanzini est une jeune et jolie personne, possedante un organe sympathétrique et passionnée, vocalisante avec une facilité étonannte, ce qui ne l’empêche pas de lier les sons en les détachant avec pureté lorsqu’elle atteint les notes les plus hardies de la gamme vocale. Admirable dans Rigoletto, la Vanzini s’est surpassé dans Lucie, qu’elle a chanté non en débutante mais en artiste de la vraie et grande école Italienne’.

The papers reported that Giovannina Vanzini had played Rigoletto before the King of Denmark and his court, that she had signed a six months contract for Milan, and that she was performing as prima donna in the Polish capital alongside established stars of the size of Zélie Trebelli, Bettini, Ciampi and Rota.

|

| Kate Morensi |

She moved on to Berlin, and to Paris and London where she sang only in private, and then to Warsaw (5 November 1866) ‘Mrs van Zandt has opened the opera season in Lucia di Lammermoor. she will sing there the rest of the winter’ ran the reports ‘She has been engaged by the Russian government for six months’, ‘applaudie à outrance’ recorded Paris press, ‘le théâtre égorgeait d’applaudissements’ at her Faust ('un nouveau triomphe'). Her Marguerite de Valois in Les Huguenots, alongside Bettini, Trebelli and the Valentine of Giovanoni, her Susanna in Les Noces de Figaro and her Martha were similarly lauded. Amsterdam and Stockholm followed.

‘Miss Laura Harris and Mme Vanzini (Mrs van Zandt) appear to be creditably sustaining the reputation of American singers’ the papers back home bridled, as the news of Jenny’s successes filtered back home: ‘Her success in Warsaw is the more decided, as the company there is composed of the best artistes from Her Majesty’s and Covent Garden, London’. ‘She is engaged to sing in Vienna in the month of May’.

I’m not sure about Vienna, but in October Jenny Vanzini turned up in Glasgow, singing ‘Il Bacio’, ‘Charlie is my darling’ and the ‘Last Rose of Summer’ at the Saturday Evening concerts.

However, she was not long absent from the stage. On 30 November 1867, Madame Vanzini opened the new season at the La Scala of Milan, singing Mathilde in Guglielmo Tell alongside Carlo Lefranc, Davide Squarcia, Marcel Junca: ‘Milanese papers speak in high terms of the singing of Mrs Jenny van Zandt at La Scala. On the opening night the royal family were in their box’.

‘The continued performances of William Tell have only increased the success of Mme Vanzini at la Scala. This young and charming singer has won, from the moment of her first appearance, all hearts, and deservedly the public favour’ wrote Le Comédie, following up with a ream of press notices acclaiming the young singer. On 26 December, she followed up as Oscar in Ballo in maschera with Sra Berini and Tiberini. The production was so successful that it was given 29 times in the season. Masaniello was scheduled to follow, and when Mélanie Reboux fell ill, Jenny was pro tem handed the role of Juliet in Roméo et Giulietta.

From Milan, Jennie progressed to London and an engagement at the Covent Garden opera. She arrived too late to take her intended place as Gilda in Rigoletto, but made her debut instead on 9 April as Oscar in Ballo in maschera: ‘This lady has a light, flexible soprano voice of brilliant quality and considerable power, with execution and style sufficient to give unusual importance to a part which has frequently been filled by far inferior singers … Mlle Vanzini’s clear, bright quality of voice and good phrasing in the incidental passages allotted to the page seemed to evidence a capability for parts of more prominent importance’ (Daily News)

|

| Therese Titiens |

Those parts were quick to come.

She followed up as Marguerite in Faust with great success ‘une Marguerite sans rivales’ cheered those watching from across the channel, then as Mathilde, and then took up the part of Gilda, alongside Chelli, Graziani, Grossi and Tagliafico. ‘Mlle Vanzini gave the music of Gilda with real expression and good taste and her acting was effective and always to the purpose. The melodious ‘Caro nome' was artistically sung and Mlle Vanzini’s dramatic rendering of the character of Gilda is full of earnest meaning and intention..’

Since, in the same season, Clara Louise Kellogg was singing at Her Majesty’s Theatre, and memories of the startling Laura Harris were still fresh, the species American prima donna was on display in London to greater advantage than ever before, and Jenny Vanzini was second to none.

|

| Laura Harris |

However, there were as ever the naysayers. The London correspondent of a paper entitled The New York Musical Gazette wrote snootily ‘‘A Mme Vanzini (proper name van Zandt I believe) has also been singing at Covent Garden. Though not a ‘star’ she is a fair artist, able to stop a gap very acceptably, and has done Mr Gye good service pending the arrival of Patti and Lucca, she has appeared in Rossini’s William Tell which was produced a week ago for the first time these three years…’

Another star-struck magazine, sighing over Patti and Lucca, allowed of Vanzini ‘a pleasant voice and sings reasonably well’.

At the end of the opera season, Jenny Vanzini went north and appeared in concert, opera and oratorio in northern England and in Scotland over the winter, returning to London in March for a fresh series of operatic performances. This year, with the combination of managers Mapleson and Gye and their forces, the stock of available prime donne – topped by Titiens and Patti – was unprecedented. But Jenny Vanzini was still there, playing Gilda to the Duke of Mongini and the Rigoletto of Charles Santley – when Ilma di Murska wasn’t doing it. ‘[She is] as good a Gilda as needs be and the way in which she warbles the delicious aria ‘Caro nome’ is as pleasant to hear as the most exacting musical ear might wish for’ ‘Her voice appears to have gained in power and her style to have progressed un finish and refinement ... the bright clear quality of voice the neat and brilliants execution and genuine earnestness of Mlle Vanzini drew forth special manifestations of approval, Her command of the higher notes (extending to the C sharp in alto), her close and prolonged shake and the general merits of her performance .. gained a success beyond that hitherto achieved here by this artist.’

The overstock of stars proved a mirage, when Titiens and Lucca both fell ill, and Jenny Vanzini ended up going on to play Leonora in Il Trovatore as well as Urbain in Les Huguenots. But somehow it didn’t work. ‘Though full of ability’, mused a perspicacious paper, ‘she has never attained the position of a leading favourite’.

She sang at the Crystal Palace Concerts, at St James’s Hall, took part in Benedict’s annual fashionable, and played further opera at Liverpool and at Covent Garden in November, when she appeared as Zerlina to the Donna Anna of Titiens and the Elvira of Sinico in Don Giovanni. She also took the soprano part in the first London performances of Sullivan’s The Prodigal Son (11 December 1869) alongside Perren, Santley and Janet Patey at the Crystal Palace.

In the early part of 1870, she went out with a concert party including Sofia Scalchi, Stockhausen, Tagliafico and della Rocca, but with the operatic ‘wars’ still ranging, the opera companies were quickly back on the road. Vanzini went with the Mapleson team, alongside Titiens and Scalchi, and found herself cast in all the most brilliant roles -- Marguerite (‘her voice is still gaining in volume and strength’), Amina, the Queen of the Night (‘we were not prepared for as fine a piece of vocalism as she displayed’), Susanna to Titiens’s Countess, Gilda – as the company made its way through Scotland, heading back to town.

During this season she sang Marguerite de Valois, Mathilde, Oscar in Ballo in maschera, Inez in L'Africaine, and since Patti was on hand to sing Zerlina, she was Donna Elvira when Don Giovanni was given. Initially advertised also to play Prascovia in L’Etoile du nord and Marcellina in Fidelio she saw those roles given instead to the newcomer Fanny Madigan, and similarly Dirce in Medea handed to Mathilde Bauermeister.

On 25 November, she made an appearance with the Sacred Harmonic Society, singing the soprano music in Judas Maccabeus, and in the same month she replaced Helen Lemmens-Sherrington in Barnett's Paradise and the Peri at Birmingham Town Hall. She also sang ‘Loreley’. She returned to Birmingham for The Messiah on Boxing Day, visited Manchester for the Halle Concerts (Jewel song, ‘truthful intonation and dramatic verve’) and when the Paradise and the Peri was given at St James’s Hall (14 February 1871) , she again took the soprano role.

She sang in provincial concerts (‘Rose softly blooming’, Jewel song, ‘Ah rammento’, ‘Voi che sapete’, Sullivan’s Lullaby), revisited the Crystal Palace, and finally returned once more to the Covent Garden Italian opera, where she repeated her Oscar and, in July, took the part of Ersilia in the production of Le Astuzie femminili with Mlle Sessi, Sofia Scalchi, Bettini, Cotogni and Ciampi.

Her next operatic engagement, however, was to travel. To travel back to her home country as co-prima donna with a new English language opera company under the management of Mr Carl Rosa, with his wife Euphrosyne Parepa Rosa featured alongside a combination of British and American artists.

And so it was that on 9 October 1871, at the New York Academy of Music, ‘Mrs Jerome van Zandt’ made her first appearance in America since her original departure for Europe, singing the title-role of Satanella, a work, till now, never performed in America, alongside Americans William Castle and Sher Campbell, and English singers Clara Doria, Harriet Aynsley Cook, Tom Whiffen and Edward Seguin. The New York Times reported ‘Mme van Zandt, the foremost attraction of the evening, demands attention at once as an artist of singular ability and as a lady of native birth. In the lyric world, some command admiration from the first, some conquer it by sheer stress of merit, and some by injudicious partiality have it unduly forced upon them. We incline, with present lights, to place Mrs van Zandt in the second category and to believe that her acknowledged European position has been honourably earned. Although well received last night the audience certainly treated her in a rather cool and tentative fashion for some time after her appearance. It was not until the close of the act that, in the very taking aria ‘The Power of Love', the unforced beauty, flexibility and range of Mm van Zandt’s voice were heard to advantage; and then the lady undoubtedly took the house by storm. An organ like this. of the true sfogato class, highly trained, extended by accurate methods to uncommon register, fairly endowed with sympathetic qualities, achieving with a certain refreshing and graceful ease difficulties given to marvelous few to compass, is rarely heard indeed…’

In a way, it posed the same question as had been posed in Britain. Mrs van Zandt alias Mme Vanzini seemingly had it all. Why was she not a ‘star’?

Two nights later, Jennie appeared at the Academy of Music as Maritana, and during the company’s voyage to the main centres, she went on to play The Maid and the Magpie, Zerlina in Fra Diavolo (‘introducing an aria from Le Serment') , Oscar in Un ballo in maschera, Zerlina in Don Giovanni, Marguerite in Faust, and when Charles Santley made his debut on the American stage at the Academy of Music as Zampa (12 February 1872), during a return season in New York, it was Jennie van Zandt who played opposite him as Camilla.

When, at the end of the tour, Euphrosyne Parepa and her husband returned to Britain, Jennie van Zandt soon followed. But she was back by the autumn and, after a turn through concert and oratorio performances (Messiah Steinway Hall, 25 December 1872), at the turn of the year she again appeared in opera, first with a new English combination (Chicago 6 January 1873), and then – in spite, apparently, of an offer to join Parepa’s company in Britain, with Clara Louise Kellogg’s company, under the management of Grau and Hess.

It didn’t take long before somebody said it: ‘Her voice is naturally better than Kellogg’s ... equally as pure a soprano, much stronger and clearer and reaches high notes with greater ease...’ The same old question. Why was it not she who was the top-billed star? But Jennie van Zandt appeared to be without vanity. She had sung a virtual second to Parepa, now she would for several seasons, whilst always playing leading roles, play a virtual second to another determined ‘star’ to whom she was arguably superior in talent.

|

| Clara Kellogg |

After the first tour of some three months, Jennie left the company, and her place to Isabella McCullough-Brignoli, but she returned at some stage, early in 1874 (Fra Diavolo, Martha), before again leaving and heading to London, 9 May 1874, en route for St Petersburg. It seems, however, that the Kellogg company made her an offer she did not refuse, and instead of going on to her engagements overseas, she retraced her steps to join Miss Kellogg and her company for yet another tour. She sang Maritana, Filina when Kellogg played Mignon, she played Elvira in Ernani, the Countess to Kellogg’s Susanna (‘a genuine triumph’, 'all the qualities of a genuine artist, a full and well-developed organ, an excellent method and considerable dramatic talent’), Marguerite, and Donna Anna to Kellogg’s Zerlina. When Les Huguenots was added to the repertoire Jennie van Zandt sang the role of ... Valentine!

On 11 October 1875, the company played a New York season at Booth’s Theatre. and Jennie shared the prima donna roles with Miss Kellogg and with the company’s third, but in no way inferior soprano, the lady who called herself Annie or Ada Beaumont and who was in reality the London Gaiety Theatre soprano Annie Tremaine.

|

| 'Ada Beaumont' |

After New York, the company headed again for the touring circuits. By now, Jenny was no longer the dazzling star of Warsaw or Copenhagen. She had, either from personal limitations or lack of ambition, allowed herself to become exactly what the Chicago press labelled her on the occasion of her Benefit ‘the accomplished seconda donna of the Kellogg Opera Troupe’. ‘There is not a more conscientious, painstaking and thorough artist on the operatic stage’ continued the review ‘Her talents deserve the heartiest recognition and the house should have been filled from pit to dome’. It wasn’t.

Now, however, things changed seriously in Jennie van Zandt’s family and career. Her daughter, Marie, had followed her mother into the world of music, and was showing signs of becoming an outstanding performer. So, Jennie quite simply put aside her own career and travelled to Italy where Marie, in her turn, studied with Lamperti. In 1878 it was announced that she, again following in her mother’s footsteps, had been engaged by Mapleson, along with her mother, for Her Majesty’s Theatre, London.

However, as it happened, Jennie made it back to the stage a little before her daughter. She, who had nearly a decade earlier been part of the early Parepa Rosa company in America, was hired for the now thoroughly established British Carol Rosa Opera Company.

In September 1878, she joined Rosa at Liverpool, singing Maritana alongside Maas, Celli, Josephine Yorke and G H Snazelle and was ‘warmly welcomed as a new gitana of rare vocal ability and much histrionic talent’. Britain got to see just how her talent had developed when the company produced Les Huguenots. The young Georgina Burns was cast in the role of Marguerite de Valois, and Jennie – who had in her time played both the Queen and Urbain -- this time played the decidedly more demanding role of Valentine, which she had first essayed with Kellogg, alongside the Raoul of Joseph Maas.

She also sang Leonora to the Trovatore of Maas, and took the title-role in a revival of Lurline. Out of the shadow of the great Italian stars, and of the pressing Miss Kellogg, Jennie van Zandt was now prima donna assoluta.

|

| Joseph Maas |

On 27 January 1879 the Carl Rosa Opera Company moved its activities to London’s Her Majesty’s Theatre, and Mme Vanzini entered on what would be her last British operatic season, playing Adriano alongside in Rosa’s English-language premiere of Wagner’s Rienzi.

Now the press referred to her as ‘[Mme Vanzini] who a few years since was one of the favorite prime donne of the Royal Italian opera’ and hailed her as ‘a great acquisition to the company, her voice being pure and powerful while her acting has plenty of animation and energy’ and summing up ‘There could be no question as to Madame Vanzini’s success’

She also played Les Huguenots ‘with great energy and excellent voice’…

On 7 May 1879 Marie van Zandt made her debut on the same stage, with the Italian opera company, singing Zerlina in Don Giovanni. She was an unequivocal success. The American press reported ‘Unusual interest attached to the debut, owing to Marie’s mother being so well known in English and Italian opera as well as the fact that rumour spoke of her in the highest terms… [She has a] charming presence, unaffected acting, and sweet sympathetic voice. London critics, as a rule, are chary of their praise of young American singers but, in this case, they have expressed extreme delight and prophesied for Mlle van Zandt a brilliant career’.

A few days later, the young singer deputised for Etelka Gerster in La Sonnambula and her success was confirmed.

My last sighting of Jennie van Zandt on the British concert platform is on 30 May 1879, when she sang in Richard Drummond’s concert at the home of Mrs Freake. My last possible sighting is at the Teatro Regio in Turin, later the same year, in Don Giovanni.

It seems, thereafter, that she devoted herself entirely to her daughter and her career, as Marie moved on to the Paris Opéra-Comique and to a long and mostly brilliant career as a prima donna.

Perhaps it is partly because Marie succeeded so eminently, and with exactly the kind of flair and public appeal that her mother apparently lacked, that Jennie is somewhat forgotten. Her daughter (after chucking the temporary ‘Marie Vanza’) somewhat cornered the musical fame of the ‘van Zandt’ name. It is perhaps also partly because she seemingly did not seek publicity, did not push herself forward – as witness her willingness to stand, for so long, half in the shadow of Parepa and Kellogg—and never, like those ladies and others, had her name billed large at the head of her own opera company. Perhaps, yet again, it is because she started her career later than might have been expected, and finished it earlier than might have been expected, at the age of 43, admittedly, but after barely 15 years as a public vocalist.

But Jennie van Zandt, Madame Vanzini as was, was and is thoroughly worthy to stand amongst that group of mid-Victorian sopranos – Escott, Harris, Kellogg, de Wilhorst, Durand -- who first and firmly established the worth of the American prima donna on European operatic stages.

Her career over, Jennie vanished so completely into the shadow of her celebrated daughter that I have been able to discover little of her later life and indeed of her death. In 1880, she divorced James van Zandt on the grounds of failure to provide. It does in fact seem that all he had ever provided her with was children. He died in Plainfield, NJ 27 December 1907, and his New York Times obituary related that he had ‘until recently [been] prominent in Boston banking circles’. Elsewhere I have picked up the odd tale rather less complimentary to his financial activities.

Jennie died in Paris in 1913.

|

| Marie as Lakmé |

Marie van Zandt (b Brooklyn, 8 October 1858, d Cannes, 31 December 1919) is said to have made her debut as a performer at the Teatro Reggio, Turin. Following her performances in London, she went on to Paris where she established herself 1858 at the Opéra-Comique (Mignon, La Chanson de Fortunio, Dinorah etc) , and sealed her fame in 1883 with the creation of the title-role in Delibes’s Lakmé. After a series of non-artistic incidents, she left the Salle Favart and made her way to other European houses, notably the Imperial Theatre at St Petersburg where her mother had been so successful, and for one season to America. She ended her career when she married the Russian medical diagnostician Professor Mikhail Petrovitch Tscherinoff of the University of Moscow (27 April 1898) and spent her later years in Russia and in France.

Of Jennie’s other children, Amelia van Zandt, who became Mrs Alexander Frederick Meyer(s), also spent her later life in France, while Dudley (b New York, 1 January 1858; d 29 San Francisco, April 1941) remained in America where he pursued a career as a theatrical manager. Of Catherine, I know absolutely nothing.