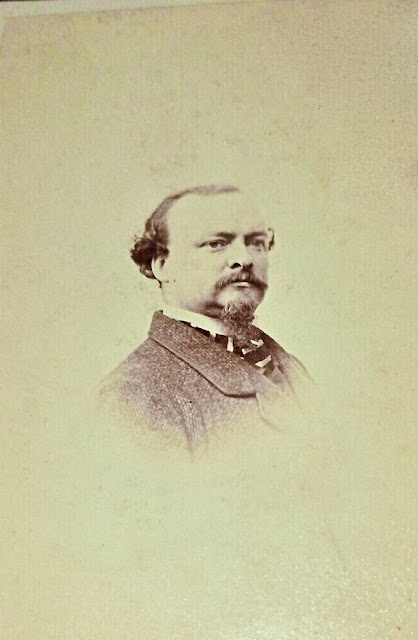

SWIFT, Joseph (b St Helen’s, Lancashire c 1827; d 3 Pall Mall, London 10 July 1869)

During the Victorian era, very few tenors from the English-speaking world made themselves a reputation in the operatic theatres of Europe. In the later part of the nineteenth century, Americans Charles Adams and William Candidus found success in Germany, but in the earlier years of Victoria’s reign only a handful of Anglophones made any sort of an impression in the world of Italian opera. There was the ‘preposterous’ Sims Reeves, of course, who cast his giant shadow over a whole era of English tenoriousness, and then … Without a doubt, and even though he made not the same name for himself either at home or away, the second place must be allowed to Joseph Swift.

So, who was Joseph Swift? ‘Mr Swift’, as he was inevitably, shortly, known in Britain, even though the Italians dubbed him ‘Giuseppe’ and the Portuguese ‘Jose’. It has been a little hard to find out, for while Sims Reeves won the repeated honour of stretch-biogs in the press, year after year, the personal background of Britain’s number two operatic tenor doesn’t ever seem to have been written about. At one concert, the press proudly acclaimed him an Irishman, which set me off on a whole false trail, for Joseph Swift wasn’t an Irishman. He was a laddie from Lancashire.

The reason that I know that, is that I have unearthed him in the two British censi of his adult life: in 1851 as a student of music in London’s Manchester Street ‘born Lancashire, aged 24’, and in 1861 in South Square, Gray’s Inn, ‘musician, 32, born St Helen’s’. On the principle that you wouldn’t say you were born in St Helen’s if you weren’t, I have dug around amongst the Swift families of Windle and Prescott and the hamlet of Handshaw (publican: Edward Swift) in the 1841 census listings, exhuming a teenaged Joseph who was a moulder, another a coal miner, another nephew (?) to a brewer, but none seemed to fit.

In January 1861, Joseph missed a Manrico at the Opera House on the grounds of ‘a most severe domestic affliction’. Sounds like a wife, but he’s supposed to have been a bachelor. A parent? That didn’t lead me to an answer either, so for a long time the background of Mr Swift remained cloudy, and he didn’t impinge on my consciousness until 1849, when he is a student at the Royal Academy of Music.

But I half-got him in the end. Joseph Swift was the son of one Richard Swift, and he wasn’t a bachelor. Just a handful of years before his death (23 October 1865) he married farmer’s daughter, Miss Elizabeth Blackhurst, back home in St Helen’s. And he seems to have been a wee bit older than he claimed… if he is the Joseph son of labourer Richard and his wife Jane born at Sutton, Prescott, St Helens in 1824. Siblings John, Ralph, Ellen, William … and, oh, another Joseph in 1832! They must have lost the first one…. So I’m not a lot nearer.

Like other young and promising tenors, Mr Swift of the RAM had the spotlight fairly quickly turned upon him, with some hopeful folk looking out for a ‘new Sims Reeves’ (the old one had plenty of mileage left however!) and others reacting equally exaggeratedly against the, at best, premature chatter. Mr Swift was, in any case, fairly clearly the most promising young man of his crop, the Academy’s other prize pupils of the time being Mary Rose, Laura Baxter, Helen Taylor and the much spotlit Catherine Browne. He, equally clearly, had a way to go. When he sang at one Academy concert, The Times reported ‘his intonation was so sharp it was painful’. And the arch pontificator of the early Victorian musical world, the rather ridiculous French Flowers, MB Oxon (‘The British School of Vocalisation’), launched at him in 1850, as part of a tirade against (other) singing teachers, a specific tirade. ‘As a specimen of an artificial voice let me instance Mr Swift who sang ‘Il mio tesoro’ at Miss Bassano’s concert. His natural voice (which is excellent) is baritone and yet he is taught to consider it a tenor by his master, notwithstanding that he has not a tenor sound in the whole range of his natural voice. In consequence of his pushing out high sounds, his voice on one occasion gave way…’

Most reactions were more measured -- ‘has a voice of good quality and exhibited intelligence’, ‘a tenor of remarkably good and even quality; he has the means, we hope he will make use of them..’ – but at this early stage of his career Mr Swift was evidently subject to vocal bloops.

During his time as a student, Swift began to make occasional appearances in professional concerts. The Louisa Bassano one, where Flowers referred to him as ‘a’ Mr Swift, seems to have been the first, but I also spot him at Miss Chandler’s do at Store Street Music Hall, at Charlotte Dolby’s at-home soirees in Hinde Street (‘Dalla sua pace’) and at the Réunion des arts, before he was brought before the wider public at the Exeter Hall London Thursday Concerts (11 December 1851) billed, in traditional style, as ‘the new tenor’. The young Louisa Pyne stole the limelight singing Rode’s Air and Variations, but Swift, praised for his ‘fine voice’, did well enough with Mendelssohn’s ‘By Celia’s Arbour’ that he was retained for the series. He also began a perfect avalanche of concert engagements: at Exeter Hall for the English Music concerts (‘The gentleman made a very respectable debut and sang ‘By Celia’s Arbour’ with great applause’), at Sussex Hall alongside Misses Pyne and Dolby and Henry Whitworth, at Crosby Hall, at St Martin’s Hall (Alexander’s Feast, Oberon and Orfeo selections &c), at John Ella’s Winter Musical Evenings and at the Exeter Hall Wednesday concerts (‘If with all your hearts’). He appeared at the entertainments given by pianist Charlotte Pearson, by Hannah Binfield, by Leslie Sloper (‘The Garland’, Gounod’s ‘Venice’), by George and Joseph Case, and at the London Tavern for Julia Bleaden, on which occasion all the praise being heaped on the young tenor got too much for one scribe who exploded: ‘There has been much talk recently about the new tenor, Mr Swift. Some have placed him but a round or two in the ladder below Mr Sims Reeves. Nonsense! There is just as much difference as between chalk and cheese… he was tame to tameness’.

If he was ‘tame’ (unshowy), Mr Swift was also ubiquitous, and as the season wound to its first height he turned out for a bevy of concerts: alongside Reeves, Manvers and another young tenor, William Fedor, at Drury Lane, at Exeter Hall for Allcroft, the City of London Institute, at the Hanover Square for the Misses McAlpine, the Ferraris, Charles Salaman, Brinley Richards (‘The Garland’ ‘sung with the utmost taste … an improving tenor’) and, when Edward Land launched his English Glee and Madrigal Union, it was Swift whom he chose as the group’s tenor, in team with Louisa Pyne, Charlotte Dolby and Frank Bodda.

In June, the new tenor was seen out almost daily: for Louisa Bassano/Wilhelm Kuhe (4 June), Otto Dresl (5 June), Allcroft at Exeter Hall (6 June), Lindsay Sloper/Miss Dolby (7 June), Charlott and Eliza Birch (9 June), and on 11 June three engagements: Emma Busby’s, Mlle Coulon’s and the Royal Society of Female Musicians concerts. He was included in the fashionable programme of Madame Anichini (‘The Garland’, ‘I Marinari’ with Ciabatta, I Puritani duet with Anichini etc), shared with Elisa Taccani the vocals at Mme Pleyel’s piano concert, visited Liverpool’s Philharmonic Hall in concert and, later, to sing Elijah with Grace Alleyne, Charlotte Eyles and Carl Formes. In London, he took part in a performance of The Creation for the Choral Fund.

London, however, was not to suffer from a surfeit of Mr Swift. Antonio Porto, the manager of Lisbon’s Teatro de Saõ Carlos (who had, it appears, a habit of popping over on the ferry, to Portsmouth, to scout the British scene for talent), had moved to hire both Mr Swift and Mr Fedor, ‘at the beginning of their careers’, for his theatre. Mr Fedor was already booked to go to Marseille, Mr Swift was available, and he went. He went in good company, for Porto had also booked the French soprano Anaide Castellan as his prima donna. Mr Swift was to be primo tenore assoluto: alongside the other primo tenore assoluto, Antonio Prudenza. Mr Swift was ‘de meio caracter’. In effect, they were to share the tenor roles of the season.

Jose Swift made his first appearance on the stage playing the role of Elvino to the La Sonnambula of Mlle Castellan and the Rodolfo of Francesco Maria Dell’Aste, and he won the plaudits of the Lisbon public (‘excellentmente recebido pelo publico’) and papers, for his ‘tenor contraltino, meliflua, muito afinada, bastante extensa…’. His style did not win total unanimity. One critic lauded his ‘vox melodiosa e delicada usandi do falsete com multa propriedade e affinacao e cana com sentimento’ but another complained that Portuguese audiences didn’t like falsetto singing and that Sr Swift should desist. I suspect that, in the terminology of the time, by ‘falsetto’ he meant head voice.

The news of the young tenor’s success made its way overseas, and Dwight in Boston reported the ‘furore’ caused by the young man who had ‘only been seen in London as a concert singer, with a very sympathetic tenor voice’.

Prudenza played in I due Foscari, Alessandro Maccaferri (‘primo tenore generico’) did Nabucco, and Swift came out again in I Puritani on 15 November, alongside Mlle Castellan, dell’Aste, and Ottavio Bartolini. He followed up as Tonio in La Fille du régiment with Ersilia Agostini and Bartolini, and in January as Gennaro to the Lucrezia Borgia of Mme Rossi-Caccia. In March 1853 he was Percy to the Anna Bolena of the same prima donna, and in April, Tebaldo with Rossi-Caccia and Agostini in I Capuleti e i Montecchi, In May he sang Polyeucte in I Martiri.

Jose (or sometimes Giuseppe) Swift was a decided success as an operatic tenor, and he was ‘re-engaged at an increased salary’ to return to Lisbon for 1853-4 and again for 1854-5. Castellan, too, returned and the pair sang La Sonnambula, La gazza ladra, and Don Pasquale together. When Otello was produced, Corrado Miraglia sang the title-role to Castellan’s Desdemona, and Swift was Rodrigo. He was also teamed as primo tenore with Amalia Angles-Fortuni in I Masnadieri and I Martiri and, with both prima donnas, as Raoul in Les Huguenots. The following season he sang the Vicomte de Sirval in Linda di Chamounix and Macduff, alongside Castellan and Bartolini, as well as repeating I Puritani, Anna Bolena, La Fille du régiment, Don Pasquale and La gazza ladra.

At the end of his three seasons at Lisbon, Swift moved on – apparently to other European theatres. His European career has come to me in fragments, often without dates or sources attached, but a reference to ‘Swift, tenore di bellissima voce , reduce or ora da Varsavia, per il corrente carnevale , al Teatro di Mantova ..’ rings a bell. He was at Warsaw 1st August-30 November 1856.

At the beginning of 1856, however, he was back in Britain. Later, it would be said that it was now that he ‘made his debut in opera at Drury Lane’ after ‘five or six years of study in Italy’. Well, as we know, he hadn’t been studying anywhere, he’d been very visibly working. And, although he’d been at one time announced to sing opera at Drury Lane, I find no evidence that he did. He was far too busy at Lisbon.

His return to London wasn’t in opera, but in some distinctly fashionable concerts. Jenny Lind and her wheeler-dealing husband set up a series of British concert appearances in London and the British provinces for the opening months of the year, and, after Alexander Reichardt had performed as the star’s support tenor for a couple of concerts, Joseph Swift took up that place for the bulk of the series. The Times spoke of the ‘beauty of his voice and the geniality of his expression’ and another critic wrote ‘This gentleman’s voice is a gift of which he should be conceited and endeavour to turn to the very best account’. However, when he shared the music of one performance of The Messiah with Charles Lockey, the inevitable comparison surfaced: ‘a very inferior reader of the magnificent recitatives in the second part when compared with Mr Sims Reeves who sang them on Monday and Wednesday nights’.

Swift moved on from his position as cavalier servant to Mme Lind to team with another prima donna, Josefina Gassier, and her husband. They sang in London concerts, and also took to the provinces where they gave performances of La Sonnambula, Don Pasquale and Il Barbiere di Siviglia, performances which seem, to me, to be Joseph Swift’s first appearances on the British operatic stage.

Through May and June, Swift was seen in concert in London (‘La mia Letitzia’, Davide Penitente, Stabat Mater at St Martin’s Hall), and again he was billed for a London opera season, this time a three-week affair at the Surrey Theatre. However, Sig Lorini seems to have sung most nights (with his wife) and I do not see Swift on the bills.

At the end of the season, he returned to Europe, cancelling a January concert tour with Mme Rudersdorff, but I do not pick up his trail again (give or take August to November at Warsaw) until January 1857 when he is announced to sing Rigoletto with prima donna Morandini at Mantua.

And, sure enough, in June a report from the Continent makes the British music press: ‘Our English tenor Swift, of whose beautiful voice artistic talent and gentlemanly manners we have great reason to be proud, after dividing the honours at the late carnival in Mantua with Barbieri Nini is taking a vacation to continue his studies under the first masters (in Milan)… he is engaged as first tenor at [the Teatro Municipale] Alessandria in Piemonte for the autumn season..’

He appeared there with Argentina Angelini in Gli ultimi giorni di Suli and La Traviata with Rosa de Ruda, and in December, the same correspondent describing Swift’s ‘continuing and increasing success’ reporting that ‘at the completion of his autumn engagement at Piemonte’s Teatro Municipale di Alessandria’, he had been taken up by Signor Merelli, Europe’s most many-tentacled operatic agent and fixer who had arranged for him to go to the Gran Teatro at Bergamo, but then shifted him to the Teatro Nazionale in Turin, when the bid was higher. Mr Swift was evidently rolling, but he was (like most tenors) still not pulling everyone’s vote. ‘If his singing was (sic) a little more refined and if he took greater pains to modulate his voice which seems to me to be as ungovernable as when he first appeared in public, I should be inclined to think he might become a good singer, but at present I cannot agree with Pirata and others who write about his lovely simpatico voice, his fine figure, his noble carriage and other innumerable qualities which as yet I cannot say that I have discovered. Of the operas in which he has sung – Traviata, Lucia and Attila – the last I think is most suited to his vigorous and energetic style…’.

I have found him singing only Attila of those operas at Turin, but I have spotted him singing La Sonnambula there, alongside Pamela Scotti and Francesco (not Federico) Monari, and also Poliuto, in the early part of 1858. From Turin, he moved on to play alongside Giulia Beltramini-Marcora and Luigia Abbadia at Rovereto (May, La Traviata, Poliuto, ‘dalla voce insinuante’), the Mauroner of Trieste (Traviata, Poliuto) and Udine, and on 11 September 1858 he made a first appearance at the Scala of Milan, cast again as Rodrigo in Otello, alongside Bettini (Otello) and Maria Lafon (Desdemona).

Still in 1858 (carnevale), he sang at the Apollo in Venice, in Don Pasquale with Albina Maray, Ernani and Poliuto with Borsi-Deleurie, and in Benedetto Zabban’s Il Conte di Stennedof alongside that most English of Italian buffos, Giuseppe Ciampi.

From there, he moved on to the Teatro di Societa at Bergamo, where I spot him in December in Rigoletto, and then – apparently no longer under the management of Merelli – to sing with his La Scala partners at the Hofoper at Vienna. Not a place where one was accustomed to hear an English tenor. Geremia Bettini, Carrion and Musiani were also engaged, but Swift sang Elisero to Carrion’s Amenofis in Mosè and Rodrigo to the Otelloof Bettini.

It seems that the Pergola Theatre at Florence followed, but before at the end of 1860, Joseph Swift returned to England, hired by Edward Tyrell Smith for his dual-headed Italian and English opera season at Her Majesty’s Theatre. It was billed as ‘his first appearance at this theatre’, and the other principal tenors engaged were Giuglini and Sims Reeves.

Mr Swift’s first appearance came rather more quickly than anticipated. Two days after the opening of the season, the already ailing Giuglini was unable to appear, and Mr Swift went on as Manrico to the Leonora of Therese Titiens. ‘A tenor voice of remarkable freshness and purity’ approved the press. Swift was also called upon to deputise for Giuglini in Lucrezia Borgia, and then more lengthily for Reeves in the title-role of the decidedly successful new Robin Hood.

On 26 December, Joseph Swift came out in his own new role, singing Raphael to the Queen Topaze of Euphrosyne Parepa in Smith’s production of Massé’s successful Parisian opera. Queen Topaze had been somewhat fiddled with (Swift, for example, sang George Linley’s ‘Light as falling snow’) and did not prove a success. The other success of the season was Vincent Wallace’s The Amber Witch in which Reeves created the lead tenor role, but Mr Swift was allowed his due, alongside the star, and appeared with Parepa in The Bohemian Girl and Il Trovatore, and in the title-role of Fra Diavolo. At the end of the Her Majesty’s season, when Smith transferred his new success, The Amber Witch, to Drury Lane for extra performances, Mr Swift took over Reeves’s original part of Rudiger.

During the operatic season, he made a number of outside concert appearances, the most unusual of which was undoubtedly an appearance, alongside his Her Majesty’s co-stars, Parepa and Charles Santley, on the programme for the opening night of London’s new and wilfully upmarket Oxford Music Hall.

In the autumn, Swift went on tour with the Her Majesty’s company. Giuglini again had the pick of the tenor roles, but Swift sang Pollio (‘the best Pollio heard upon the Dublin stage’ appreciated the Irish press) and Almaviva in Il Barbiere di Siviglia and Giuglini’s roles when required.

He followed up with a similar programme in Giulia Grisi’s ‘Farewell Tour’ of Britain, singing Norma, La Sonnambula and the rest of the Grisi repertoire when co-tenor Galvani didn’t appear.

Norma, in fact, was now becoming Mr Swift’s mascot role on the British stage. ‘A well built, good-looking Pollio with a pleasant voice’, Willert Beale remembered in his memoirs: ‘He played (Pollio) with remarkable conscientiousness and his voice resounded with that manly intonation which we have before noticed…’ nodded the Manchester press ‘few visitors to Manchester have found more favour’.

The Grisi tour ended 2 December, and Mr Swift continued on the rounds of the concert platforms. At Christmas, he returned to Manchester to sing The Messiah with Mme Rudersdorff, Fanny Huddart and Formes (‘realised fully al that we had expected of him’), and in the early part of 1862 he performed at London concerts given by Edward Land (‘Love sounds the alarm’ ‘with force and energy’), the Marchisio sisters (‘Breeze could I thy pinions borrow’ Mendelssohn and quintet with them), Howard Glover, at the Crystal Palace (‘Love sounds the alarm’, Amber Witch duet with Parepa) and with the Vocal Association where he took part in the first concert selection from Benedict’s The Lily of Killarney. He appeared briefly in opera with Jenny Baur’s company, and sang in The Messiah and Elijah with the National Choral Society at Exeter Hall, alongside Florence Lancia, Dolby and Santley (‘Both Mme Lancia and Mr Swift would probably find it advantageous to devote especial attention to the oratorio school of singing for which they are in every sense well fitted’).

|

| Carl Formes |

He was on hand again for the Italian opera season, where he again sang Lucrezia Borgia and Il Trovatore in place of Giuglini (‘Mr Swift whose fine voice and musical intelligence were always admired has made remarkable progress and may be complimented on having supplied, with as much ability and so entirely to the satisfaction of the patrons of Her Majesty’s Theatre, the place of an artist of such high standing’). In the last part of the season he replaced Armandi in Norma ‘and was a decided improvement’. The Musical World permitted itself to wonder why the Pyne and Harrison company had preferred to hire George Perren as their second leading tenor when a vocalist with the stage ease of Mr Swift was around.

In the autumn, he went on the road with Edward Land’s concert party, with Marie Cruvelli, Madame Gassier and the bass Josef Hermanns, to fine receptions and reviews (‘a powerful tenor voice and sang with great animation’) in which the word ‘energetic’ appeared regularly. So, alas, did the word ‘Reeves’: ‘next to Mr Sims Reeve (facile princeps) he is one of our most accomplished tenors’, but since Swift necessarily performed some of the same music as his contemporary it was inevitable. When the party sang at John Russell’s concert at the Hanover Square Rooms, the Musical World acclaimed ‘one of our most genuine English tenors with a voice alone which should make his fortune’, and another critic came up with the delightful encapsulation of Reeves’s megastardom over his performance of ‘The Savoyard’ and ‘The Stolen Kiss’: ‘in which Mr Swift by no means unworthily emulated his preposterous contemporary’.

Swift spent Christmas singing English opera in Ireland with Annie Tonnellier and Emma Heywood, and it seems to have been there that he introduced Balfe’s new song ‘Si tu savais’ which would become his concert battlehorse over the years to follow.

On 29 May he made his first appearance with the Sacred Harmonic Society, singing The Creation, and the Daily News proffered ‘The Sacred Harmonic Society could not find a more satisfactory substitute for Mr Sims Reeves than Mr Swift. He is not a showy demonstrative singer and may perhaps be deemed rather tame. But this we think would be a mistake. His manner is quiet and his style is pure and simple. He has a full mellow voice and possesses both taste and expression.’ So what happened to ‘energetic’?

Swift sang his way through the concert season, delivering ‘Si tu savais’ with regularity, and in the autumn he took a prominent part in Alfred Mellon’s Covent Garden Proms (‘The Savoyard’, ‘The Stolen Kiss’, ‘Si tu savais’, Balfe’s rifle song ‘The Banner of St George’) before joining the company at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. He appeared there as Auster, Spirit of the Storm in the stage version of Manfred, and in the new year as the singing a Lord in As You Like It, but in between times he returned to Her Majesty’s Theatre to replace Sims Reeves in the title-role of Faust for the final performances of the initial English-language run of the opera. He also stepped in, in his decidedly useful fashion, as temporary leading tenor for the touring Rosenthal company.

On 4 June 1864 he mounted what seems to have been his only personal concert, at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane with a grand bill of mostly English singers (Reeves, Santley, Mme Lemmens-Sherrington, the Weisses &c).

Later in June he appeared, ‘of Her Majesty’s and Drury Lane Theatres’, at Astley’s playing Tom Tug in The Waterman for E T Smith’s Benefit, and in September he joined up once more with Mapleson’s Italian Opera company. He was, as ever, Pollio, to the Norma of Titiens, but also sang Manrico, Oberon to the Huon of Italo Gardoni, and Jacquino in Fidelio.

In November, William Harrison (now without Louisa Pyne) ventured a season of opera at Her Majesty’s and Swift took part, playing Edgardo in Lucia di Lammermoor, Ottavio in Don Giovanni, Faust opposite Anna Hiles, La Sonnambula alongside the debuting Susie Galton, and creating the part of Agamemnon in Levey’s operetta Punchinello. He took time out from Her Majesty’s to dash to Dublin to replace poor Giuglini for the last time, returning to London to take the title-role in Harrison’s production of Maillart’s Lara, alongside Louisa Pyne. Lara had limited appeal.

During the concert season of 1865, Mr Swift was less in evidence, and when he again went out with the Italian opera he seems to have played only Jacquino, before joining up with Mrs Pyne Galton as the tenor for the touring company which was to showcase daughter Susie in pieces of Faust, Il Trovatore and La Sonnambula and the operettas Punchinello, Fanchette, Castle Grim, The Rival Beauties et al. ‘His voice is always heard with rapture’ wrote a critic.

If his voice were in good shape, however, something else clearly was not. Apart from occasional appearances with the Galtons, Mr Swift was conspicuously absent from the theatre and concert bills of 1866 until August of the year when he was announced to take to the road as tenor with the Rosenthal opera company…

Did he go? Every review I see speaks of William Parkinson.

If he did, it was his swansong.

At an age of not yet forty, Joseph Swift had done with the world of music.

I have a death certificate in front of me. I bought it many years ago, when ‘Mr Swift’ did not, for me, even have a christian name, and the Internet did not exist. But I found a brief announcement of his death in the press of July 1869 and I hastened me to the black books at the London Registry Office. From them, I found the only possible match: a Mr Joseph Swift, who died, aged 42, at number 3 Pall Mall on what looks like 10 July 1866. Now I know that ‘Joseph’ is correct … and the Musical World, I too late find, actually found an infime space to record tersely ‘On July 10th at his residence in the Opera Arcade...’ So, it is he. Even if the Opera Arcade and Pall Mall seem to be adjacent, rather than precisely the same thing. But on that death certificate, under profession, it says ‘confectioner’.

Is that what became of Joseph Swift in the last few years of his life? Did ill-health force him from the stage and the concert platform, and into another way of making a living. Or did he lose his voice? The youthful death would seem to point to an illness. The certificate says ‘chronic phthisis of...’ what may be ‘heart’ and ‘serious apoplexy’.

So, annoyingly, my information on the last bit of Joseph Swift’s life is almost as fuzzily uncertain as that about that on the first part.

What is not uncertain, though occasionally, maybe, a little Continentally incomplete, is the professional part in between to two fuzzy areas. Mr Swift deserves his place in the upper ranks of Britain’s Victorian tenors.

Coda: I found this piece of music as 'sung by' our Joe. Alas, I can't find him performing it. However the fashionable army man, Francis Mountjoy Martyn was only a Major in the first half of the 1850s, until his promotion to higher ranks. Copac says it was published in 1852 or 1867. I think we have to go for 1852, yes?

No comments:

Post a Comment