This delightful photograph of three small part girls from the 1869 Strand Theatre production of the burlesque of Joan of Arc surfaced the other day. Just my period! And I have a playbill, too ...

Here we have Isabella Goodall (b Liverpool 10 August 1847) daughter of John and Elizabeth Goodall and a member of a decidely musical, theatrical and ill-fated family. She married in 1871 one Edward Rowland Fryer, wine merchant, whom she left in 1876 and divorced in 1880 for serial adultery notably with actress Nellie Vane ka La Feuillade. Musician father, John, vocalist-actress Annie, and brother Tom all died before their time, but Bella made it to her forties and died 3 February 1884. Her theatrical career began at the Theatre Royal in her native Liverpool before, in 1865 she joined the Bancrofts at the Prince of Wales, played principal girl in panto at the Surrey, in Black-Eyed Susan et al at the Royalty whence she moved to the Strand, where we (and Mr Fryer) find her. She guested at several provincial houses (Birmingham, Nottingham, Leeds &c), succeeded Kate Santley in The Black Crook (1872) at the Alhambra, appeared in Amy Sheridan's 'unclothed' Ixion (1874) and remained on the stage until her mother's last illness (1883). She died a few months after her parent.

I don't know much about Louise Claire. I doubt it were her real name, which makes things tough. I spot her first at Margate (1863). then at Doncaster with Nye Chart, Birmingham, Leicester (Maria in School for Scandal) before 27 September 1868 she joins the Strand company. 16 April 1870 she moved to the Vaudeville, but she soon returned to the Strand .. after 1871 I spy her no more. Although there are a Miss Georgie Claire, and a Miss Rose Claire ...

Amelia ('Milly') Newton (x July 1859; d 18 April 1884) was born Amelia Smith, the daughter of Richard Smith, joiner and scenemaker, and his wife Alice Robinson. She played small parts at the Strand and the Vaudeville and married star comedian and manager Thomas Thorne. They had a daughter, Milly Hammond Thorne (19 October 1872, Mrs Strangways), and separated.

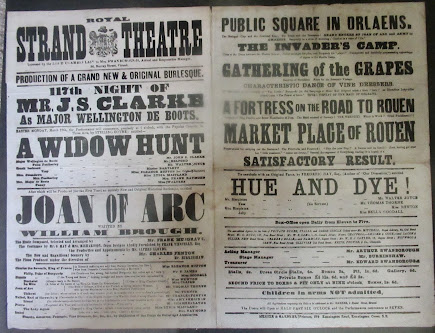

JOAN OF ARC

Versions of the historical tragedy of Jeanne d'Arc have been the subject of a number of serious stage pieces, including Schiller's 1801 play (Die Jungfrau von Orleans), the operas of Hovens and Volkert which were based on it, a Drury Lane opera of 1837 (30 November) with a score by Balfe, and more recently Verdi's Giovanna d'Arco and Honegger's well-known Jeanne d'Arc au bûcher (1938/1950). G B Shaw's Saint Joan drew some humour from the tale, but even the play of this most promising of musical comedy librettists has never seemed likely source material for the musical theatre.

Nevertheless, Joan has served as the subject of a handful of musical shows, of which the first, and the nearest to successful, were burlesques: an early Olympic Theatre piece Joan of Arc, or the Maid of all Hell'uns by Thomas Mildenhall (5 April 1847), a William Brough Joan of Arc staged at the Strand Theatre (29 March 1869) in which Thomas Thorne starred as Joan at the head of an Amazon ballet of soldiers.

|

| Bella Goodall (Dunois), Louise Claire (La Hire), Amelia Newton (Duchâtel) |

Another Joan of Arc was produced by George Edwardes at the Opera Comique (17 January 1891).

Authored by the new-found writing team of Adrian Ross and composer F Osmond Carr in collaboration with the comedian John L Shine, this last piece had a Joan (Emma Chambers) from the village of Do-ré-mi pursued by the King (Shine) to use her talent for visions to find a winning system for him to use at the Monte Carlo roulette tables. Joan and her boyfriend de Richemont (Arthur Roberts) go off to war equipped with the great sword of Charlemagne, but Joan is captured and condemned to the stake only to be saved when the British troops succumb to their national malady and go on strike. The coster number `Round the Town' performed by Roberts and Charles Danby as Joan's father, and Roberts's burlesque of a solar-topeed Stanley, describing how `I Went to Find Emin', were high spots of the evening. Neither of them, of course, had anything more to do with Joan of Arc than did an episode in which the whole French court crept up on the English, disguised in blackface, to sing a coon chorus `De Mountains ob de Moon', but all three songs became hits. The show enjoyed some scandalous moments, firstly when the `strike' part of the plot ‘offended’ some loud (and allegedly planted) members of the first-night audience, and then through the fact that shapely Alma Stanley wore no trunks over her tights. Politics proved more powerful than propriety. The tights stayed, the strikes were cut, and the show became a jolly, anodine and successful entertainment until the `new edition' alterations went in. This time it was Roberts's new hit song `Randy, Pandy O' which was seen as being offensive -- to Randolph Churchill (which it was undoubtedly intended to be). The words were changed to `Jack the Dandy, O' and no one was fooled. The show had a fine run at the Opera Comique (181 performances) and subsequently moved to the Gaiety Theatre for another 101 nights, prior to a strong career in the provinces and in the colonies.

|

| Emma Chambers |

After this rather undignified treatment, Joan was left alone by the musical theatre for a good, long time, but she surfaced on Broadway, in 1975, as the heroine of what seemed to be a new burlesque, Goodtime Charley (Palace Theater 3 March), in which Joan was portrayed by the leggy, glamorous dancer Ann Reinking and the Dauphin by Joel Grey, and then again, in the era of `serious' musical plays, in both Ireland and in England. Graínne Renihan was Ireland's Joan to `the witness' of Colm Wilkinson in the musical Visions (T C Doherty, Olympia Theatre, Dublin 24 May 1984), whilst first Siobhan McCarthy, and then Rebecca Storm, went to the stake along with England's unfortunate Jeanne (Shirlie Roden, Birmingham Repertory Theatre 16 September 1985, Sadler's Wells Theatre, 22 February 1986). And if France left its serious heroine seriously alone, French-speaking Canada did not. A Jeanne la Pucelle (Peter Sipos/Vincent de Tourdonnet) was mounted at Montreal’s Place des Arts in 1997 (7 February). Denmark followed suit in 1998 with what assuredly and sadly will not be the last attempt to foist a singing Maid of Orléans on to musical-theatregoers.

|

| Geraldine Farrar had a go at Joan |

And this version of the drama popped a popular ditty into the proceedings!