Just weeks later, the English Opera House put up another new show, and scored another success. This was an English version of Cosi fan tutte adapted under the title of Tit for Tat, or the Tables Turn’d, and alongside Joseph Wood, Thorne, Abigail Betts and Elizabeth Feron, Mary Cawse was cast in the role of -- was it the first English Dorabella? The critics complained again that ‘Miss Cawse wants expression’, but the audience didn’t seem to think so, and she was encored in her ‘A playful serpent gliding’. |

| Fiordiligi and Dorabella |

After The Bottle Imp and Tit for Tat, the season was a little less forthcoming in worthwhile novelties. Both the Misses Cawse were cast, in their usual ingénue/soubrette combination in a so-called ballad opera Not for Me (23 August, Der neue Paris) with music by Ludwig Maurer (Mary contributed ‘Ah how unsure doth beauty seem’ and Harriet ‘True it is that beauty goes’), and Mary played the ingénue disguised as a sailor in the less than effective The Pirate of Genoa (5 September, music: Joseph Weigl) and Juliette in an afterpiece Military Tactics, as well as Elizabeth, Frankenstein’s sister, in a revival of Peake’s Presumption.

The three months in the Strand finished at the beginning of October, and the Cawse girls returned to Covent Garden, where Harriet was seen as Hymen in As You Like It, and Mary as Lavinia in Native Land, Bertha in the house version of Der Freischütz, Lucinda in Love in a Village (‘more than ordinarily successful’ singing ‘Together then we’ll fondly stray’), as well as in more performances of Carron Side and The Bottle Imp where Harriet, too, repeated her original role.

In October, The Merry Wives of Windsor was presented, with Mary playing Ann Page ('Miss Cawse was all curls and giggles; a combination she appears to deem indispensable as an actress. She will discover her mistake in time’) singing duets with Wood as Fenton (‘Love like a shadow flies) and Vestris (‘I know a bank’), and she also appeared in Rosina (Phoebe), The Duenna (Louisa) and, with Harriet, in more performances of Il Seraglio. Harriet, less in view for the moment, was ‘first peasant with a song’ in a Thomas Wade drama, Woman’s Love.

Harriet took the larger share of the work when the oratorios season came round, whilst Mary came out as Estelle de Ponthieu in yet another new opera The Nymph of the Grotto. She was also called in to replace Mrs Knyvett in Acis and Galatea in the concerts, and when Comus was mounted, she took the very vocal part of Sabrina, whilst Harriet was ‘second spirit’. In The Castle of Andalusia, Harriet – still, of course only seventeen years of age and tiny -- played the boy, Philippo.

When the pair returned for the 1829 season at the English Opera House, however, Harriet came a little more into prominence. She introduced an ingénue role, as Julia in Hudson and Sidney Nelson’s The Middle Temple (‘Maidens try and keep your hearts’), and then appeared opposite Miss Kelly as the juvenile of the drama The Sister of Charity. Her performance, and her song ‘I won’t be a nun’ (‘played with great judgement’ ‘sang a song with such intelligent innocence as to secure an encore’) went far to help the play to a decided success.

Mary played alongside Sapio and Miss Betts in The Robber’s Bride (15 July) and took the role of Amaranthe in The Springlock (18 August, music by Rodwell), the second of which proved popular as an adjunct to The Sister of Charity and, later, to other pieces, and the two sisters came together again in the other major hit of the English Opera House season, an English version of Marschner’s opera The Vampire (25 August). Alongside Henry Phillips, as the vampire of the title, Mary was the Greek ingenue, Ianthe, the vampire’s first love, and Harriet was the soubrette, Liska, the vampire’s last sought victim. ‘Her first song was sung with a feeling and expression that called forth an immediate encore’ reported the Morning Chronicle going on to quote the whole words of ‘From the ruin’s topmost tower’. The Examiner wrote ‘The two Misses Cawse both played and sang with excellence and attention. We are the better pleased to offer this tribute to the elder lady because we have lately exhibited a different impression .. The younger of the sisters above named perfectly charmed us with her general deportment, as well as the exquisite style and correct intonation with which she sang the two sweet airs allotted to her’.

The Vampire gave Arnold, the two Misses Cawse and all concerned, a sizeable hit. Their final new piece of the season was a little operetta Sold for a Song (5 September, Alexander Lee/Haynes Bayley) in which they played alongside Mr Wood, in a triple role.

Back at Covent Garden, there were more successes to come. If Shakespeare’s Early Days (20 October, with Harriet as Titania), The Night Before the Wedding and the Wedding Night (Les Deux Nuits, 17 November) with music by Boieldieu and Bishop (Harriet sang ‘The butterfly borne on a zephyr’), and The Royal Fugitive (with Mary in the role of Flora Macdonald ‘singing some pretty Scotch airs with taste and feeling’) came and went, and a reprise of The Waterman with Wood and Mary served largely to provoke the publication of an engraving which, in this century, libraries the world round have convinced one another is Harriet. It is not.

However, each sister was to have her hit. Mary was cast in the role of Lodine in a version of Robert the Devil, Duke of Normandy which turned out a grand success, and in which her song ‘The Little Blind Boy’ (music: John Barnett) was one of the musical hits.

Harriet (or ‘little Cawse’ as the press still dubbed her) was given another boy’s part: the newest remake of Pippo of La gazza ladra as ‘Petit Jacques’ opposite the Ninetta of Miss Paton in the Henry Bishop version of Rossini’s opera as Ninetta or The Maid of Palaiseau. ‘Miss H Cawse played the slender youth very modestly and sung as she always does in excellent taste...’ the press reported. Mary later took over the supporting role of Madelon in this piece.

Mary played the role of Louisa Grant in the sufficiently successful Fenimore Cooper spectacular The Wigwam, but both girls found roles which they would play over and over again in the seasons to come, as Clorinda and the Fairy Queen in the Rophino Lacy version of Cinderella.

Before the 1829-30 season ended at Covent Garden, Harriet appeared in the title-role of Black Eyed-Susan (‘Harriet Cawse made a nice genuine little girl, such as any man or sailor might have loved and was delicate enough not to mince the matter or shrink back when the honest tar took her in his arms..’) and Mary alongside Misses Paton and Forde in The Maid of Judah, and both were – at eighteen and twenty-two respectively, thoroughly established as principal players in the patent theatre.

During the off season, Harriet returned to Arnold’s management, this time at the Adelphi Theatre, where she played in repeats of The Sister of Charity, The Vampire, The Middle Temple, The Bottle Imp, Midas (Nysa) and in her sister’s role in The Springlock, and introduced Constance in The Skeleton Lover (‘sang a little romance [‘A tear will tell him all’], alongside the Keeleys, with that quiet elegance that she gave to the story in The Vampire), Lady Julia in The Irish Girl, Sentry the maid in the Barnett operetta The Deuce is in her (‘Oh men, what silly things you are’) and Therese in The Foster Brothers (‘Miss Cawse united acting with singing and in a very promising way too. She has feminine manners, a highly agreeable and cordial smile, and knows how to unite delicacy with emotion’).

Mary, on the other hand, joined Malibran and Mrs Knyvett as a soloist at the decidedly high-class Three Choirs Festival in Worcester.

Once more, the pair returned to Covent Garden, where in the first part of the season Mary—apart from the role of Cecilia in The Pilot -- mostly repeated her former roles, including at Christmas the inevitable Cinderella, and Harriet played parts in the musical play The Carnival of Naples (Zoranthe, 'Sweet as fond the wild bee sips'), The Stranger (Annette), As You Like It (Phoebe), sang in Romeo and Juliet and joined Mary, as Leola and Ninetta, in performances of Clari.The new year, however, brought new successes. Harriet got the top song in the role of Karoline Klaffen in The Romance of a Day (‘The Marriage of the rose’), and both sisters were cast alongside Miss Inverarity and Wilson in Azor and Zémire. Harriet played Lesbia and Mary, Fatima. At the same time, Harriet took part in the venerable Philharmonic concerts where she was seen on their programmes on a number of occasions in mostly ensemble work.

Mary found the public eye in a slightly different way: ‘A rumour is very prevalent at the West End of the town that a noble Earl with a musical cognomen has had good cause shown to him to espouse a certain fair vocalist’. The vocalist was Mary, the nobleman was the Earl of Fife, and whatever else he did, he didn’t marry her.

Harriet again spent the off-season at the Adelphi Theatre, where Arnold brought back his successful repertoire of previous season (The Sister of Charity, The Bottle Imp, The Springlock, The Irish Girl, The Middle Temple, Midas etc), he also brought out a number of new works, the most ambitious of which was a piece written by Fitzball and composed by Ferdinand Ries under the title The Sorceress (4 August 1831). This was a blatant attempt to recreate the successful formula of The Vampire, and a large central role was written up for Harriet as a maid who disguises herself as a witch and tracks down the murderer (Phillips) of her father. The parallel went so far as to call the character again by the name of Liska. She was well supplied with music – the ballad ‘Too brave for such dishonour’, the ‘wild chant’ ‘On the wings of the wind’, the trios ‘Tomorrow we keep carnival’ and ‘These women, these troublesome women’ – but the score failed to impress: ‘Miss H Cawse has a ballad – and few can sings ballads like her – but it is not so good as her ballad in The Vampire’ ‘[she sings] a malediction on the murderer of her father … This is rather in a higher strain of lyrical tragedy than we should expect in a ballad written purposely for Miss H Cawse who expresses all the gentler passions with such deep and true feeling’.

The Sorceress – in spite of Harriet and Phillips – was at best a half success.

Less pretentious, and more successful, was another Fitzball piece, a comedy melodrama with a Greek setting, and music by Rodwell, entitled The Evil Eye, and featuring ‘Miss Poole the little and Miss H Cawse the lovely’. Harriet had ‘a pretty little character in which she sings with even more than her usual simplicity and pathos’ as Phrosina (‘Gird up thy sabre, gallant Greek’), and The Evil Eye joined the oft-revivable repertoire.

A little operetta entitled Old Regimentals in which Harriet played the role of Eva, and a new Peake piece, Comfortable Lodgings, in which she was Antoinette, made up the total of the season’s original offerings.

During the season (31 July) Harriet also played an outside engagement when she was summoned to take part with Mrs Knyvett, Miss Masson and Horncastle in a State Concert.

The first part of the new Covent Garden season saw both Mary and Harriet cast in a good role apiece. Harriet took the title-role in a revival of Artaxerxes, mounted for the debut of the young Jane Shirreff (‘Miss H Cawse in lovelocks made the Persian prince as effeminate as possible but her singing, especially ‘In Infancy’, made some compensation for the defect’) and Mary was given the part of Lady Allcash in Rophino Lacy’s adaptation of Fra Diavolo to the English stage. She and George Penson made ‘the very pink of a noble fop and the fine lady’ in a production which went on to become a classic.

The season held nothing else equivalent – Harriet sang Agatha in Brother and Sister, Mary was Lucinda in Love in a Village and Wilhelmina in The Waterman with Braham, they fulfilled their parts in more Cinderellas and played the two juvenile ladies in a piece called Born to Good Luck, or an Irishman’s Fortune, put together by Mr Power to star himself as the Irishman in Naples of the subtitle. Harriet sang in The Messiah at the oratorios (‘O thou that tellest’ and ‘He was despised’ 'in correct and musician like style',) and Mary was Barbarina alongside Misses Shirreff, Inverarity and Taylor, in The Marriage of Figaro for Kemble’s Benefit. She also took over Miss Forde’s role of Sophia in Romance of a Day, and appeared as Cepherenza, Princess of Honana in the spectacle, The Tartar Witch and the Pedler Boy.

With their contracts at Covent Garden now at an end, the two sisters now went separate ways. Harriet returned to Arnold, now retrenched at the Olympic Theatre, after losing money at the undersized Adelphi, for another season in which she added the roles of Rebecca Buzzard, the villain's wife, in Peake’s highly successful The Climbing Boy, or the Little Sweep (in which she made a particular success with Hawes’s ‘Poor Mary’) and Henriette, the maid, alongside Miss Kelly in T F Millar's 'operatic drama' The Conscript’s Sister (‘Miss Cawse had one very pretty song which was loudly encored’ ‘[she] did more for her music than the music did for her’).

Mary, in her turn, was engaged for the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane and she opened there on 23 September 1832 (‘warmly received on her entry on a new scene’) playing Daphne in Midas alongside the Nysa of Miss Betts and the Apollo of Miss Ferguson. Apparently, the respective heights of the two ‘sisters’ provided some unexpected comedy in the Quarrelling Duet ‘which they sang well’. And apparently Mary made it obvious that the part was a bit lighter than she might have wished. There were few Fra Diavolos this season, however, not till the very end. Mary went on to play as cast in Der Freischütz (Agathe/Rose), Mr and Mrs Pringle (Clarissa Robinson), Guy Mannering (Julia to Miss Betts’s Lucy), Bluebeard (Irene), The Clandestine Marriage (Chambermaid), the new Pocock/Bishop opera The Doom Kiss (Christine, ‘sang with much ability’), The Maid of Cashmere (Zilla to the Leila of Miss Betts), The Agreeable Surprise (Fringe), The Lord of the Manor and, finally, came the big one. But not for Mary. The first English La Sonnambula starred Maria Malibran, Abby Betts got the role of Lisa, and Miss Cawse was cast as the Teresa. Needless to say, the beautiful Miss Cawse ‘hardly looked sufficiently matronly for Amina’s mother’.

Harriet, in the meantime, returned to Covent Garden. In the early season, she appeared in the drama His First Campaign (1 October 1832), playing ‘a little Flemish sutler, Gertrude, with Miss Poole as an even smaller English drummer boy’ in a piece voted ‘the best laugh since The Invincibles', and singing ‘O'er the snow’ by Mori and Lavenu, and then in an adaptation of Adolphe Adam as Zanettte in The Dark Diamond (5 November, 1832, ‘Miss Shirreff and Miss H Cawse as Zanette had nothing earthly to do but to look pretty and sing beautifully and we readily compliment them on their complete success’, (‘Sang very delightfully the music which was allotted to them’), as well as repeating Cinderella, Artaxerxes (‘appeared to great advantage’) and other regulars, and in November she played the part of Anneli in a version of William Tell.

In February and March 1833, she sang the role of Elizene in the Rossini/Handel pot-pourri The Israelites in Egypt and a thoughtful critic wrote; ‘there is something so unpretending in her excellence that she is sometimes in danger of being passed over without just notice. Let other singers be where they will, she is always in tune and often brings them back from their wanderings…’

Now, however, after nine seasons at Covent Garden, Harriet Cawse, finally out of her teens, moved on. And she moved, to some surprise, to the King’s Theatre. To London’s Italian opera. She was initially announced to play Pippo in La Gazza ladra, alongside Rubini and Mme De Méric, but, for reasons unannounced, was replaced by the indifferent Mme Castelli. The press was unhappy: ‘if there is no impediment from language she would be a great acquisition to this stage which has suffered severely of late by the want of precisely such a combination of person, voice and action as are found in her’.Instead, Harriet was brought out 2 May 1833 as Smeaton, alongside the Anna Bolena of Pasta, Rubini, Tamburini and Mme de Méric. ‘A very able representative’ wrote The Court Journal ‘she sang the music of the part in a manner which gives promise of future excellence. The aria ‘Deh, non voler’ was given with good taste and expression. The same will apply to the recitative ‘E ‘sgombro il loco’ and the following aria ‘Ah! parca’. Miss Cawse will be found an acquisition to the theatre’. Others however were less sanguine: 'very pretty .. but her voice is not bold enough for so large a building. You may hear her in the stalls but not far beyond them’ (Times), ‘pretty Miss Cawse .. shines but as a star of very inferior magnitude in the sphere of the Italian opera’.

The management obviously agreed, for Smeaton was Harriet’s only role at the King’s Theatre.

Mary, similarly, played only the one season at Drury Lane, but she moved on, directly, to her third major London stage, at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket. There between June and November 1833, she played a vast series of roles in the theatre’s repertoire pieces – Mattie in Rob Roy, Louison in Henri Quatre, Julia Mannering in Guy Mannering, Louisa in The Duenna, Lucinda in Love in a Village, Susan in Sweethearts and Wives, Christine in The Young Quaker, Laura in Lock and Key, Harriet Steady in All’s Right, Stella Clifton in The Slave, Ninetta in Clari, Semira in Artaxerxes, Isabel in The English Fleet – almost always as second or third lady to Miss Turpin or Eliza Paton. Miss Cawse had, it seemed, become securely a supporting rather than a leading player, and the reason was not far to find. She was still getting the same kind of review that she had at her debuts: ‘Miss Cawse executes very well but she seems totally deficient in sentiment’.

Mary, however, did not stay with the situation. She preferred to be a big fish in a smaller pool, and so she quit London and took an engagement as prima donna at the Theatre Royal, Hull. On the 2 December 1833, Miss Cawse made her first appearance in Hull, singing Susanna in The Marriage of Figaro ‘an efficient prima donna and a lady of considerable personal attractions’, and she became immediately a local star. The theatre’s advertisements in the months that followed billed the names of the pieces to be played, and the role that Miss Cawse would play. And that was all. Not a mention of anyone else in the company, even when Miss Cawse’s role was not the most important. The list of roles – in opera, musical comedy, drama and comedy -- was, in the way of stock houses, impressive in its rate of turnover – The Barber of Seville (Rosina), The Irish Tutor (Mary, with songs), Charles the Second, Guy Mannering (Julia), The Marriage of Figaro (Susanna), The Padlock (Leonora), The Waterman Wilhelmina), Paul and Virginia (Virginia), His First Champagne (Harriet Bygrove), Love in a Village (Rosetta), John of Paris (Princess of Navarre), A Roland for an Oliver (Maria Darlington), The Beggar’s Opera (Polly Peachum), The Quaker (Gillian), Midas (Daphne), The Wedding Gown (Margaret), The Lord of the Manor (Annette), Town and Country (Taffline), The Chimney Piece (Mary), The Housekeeper (Sophy), Inkle and Yarico (Wowski), Mogul Tale (Fanny), Gustavus of Sweden ..

She also sang at the Hull Phiharmonic concerts and the Hull Choral Society concerts and was hailed as ‘a lady of transcendant ability as a vocalist’.

In fact, Miss Cawse’s unbilled partner at the theatre, and also in some of the concerts, was a Worcestershire tenor, a‘pupil of Liverati’, by name of Edmund Edmunds. And on 1 March 1834 at Holy Trinity Church, Hull, Mary Cawse became Mrs Edmunds.

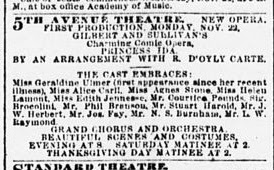

|

| Edmunds in fine comapny in Edinburgh |

The couple played out their contracts at York, Liverpool and Manchester during 1834, and then they retired to Edinburgh, where they became teachers of singing, and Mary bore six children before her death from bronchitis in 1850. ‘The deceased was an accomplished musician and will be long remembered (in conjunction with her husband) by the attenders of the late Choral and Philharmonic Societies and the Theatre Royal of this place about 15 years ago as a singer of a very superior order’ regretted the Hull press. Mr Edmunds (b Worcester 22 July 1809) lived on to a long and successful career as one of Scotland’s senior singing coaches, a second wife and many more children before his own death in 1892.

In an effective career of just eight years, Mary Cawse truly did play, as many other claimed, at ‘the principal theatres of London’, but she found her greatest success in the final theatre of her career, where she achieved the stardom that was not to be hers around such as the Misses Inverarity, Shirreff and Paton.

At her sister's retirement, Harriet Cawse was but twenty-two years of age, and she had still a good many years of career left to her.

After her experience at the King’s Theatre, she went on to sing at the 1833 Norwich Festival, and then joined the company at Drury Lane, where she was cast as the heroine of a 'grand melo-dramtic romance' entitled Prince Lee Boo which featured Mme Celeste in its title-role and T P Cooke as yet another sailor, as Lethe in the pantomime St George and the Dragon, as Maggie Lauder in the play Anster Fair, and then as Madame Girot in a version of Pré aux clercs entitled The Challenge (1 April 1834). In the role of the innkeeper’s wife, she sang ‘Time is flying’ and joined in a duet with Seguin, as her husband. She was also heard during the season in John of Paris (Rosa), The Pet of the Petticoats, The Cabinet (Leonora) et al, and between times sang in the Royal Musical Festival at Westminster Abbey where she gave ‘Thou shallt bring them in’ in ‘a very simple and chaste manner’.

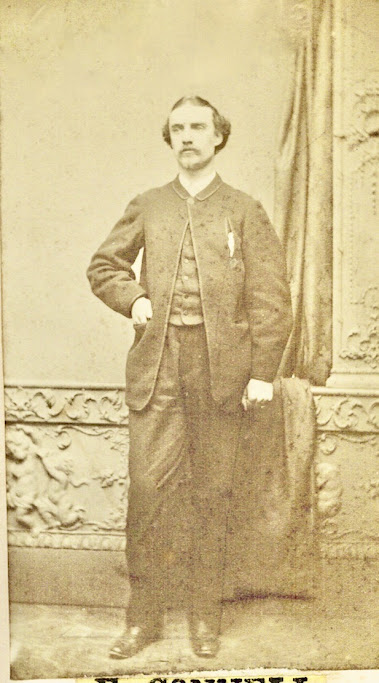

|

| This seems to date from c1834 |

When the 1834-5 season opened at the patent theatres, Harriet began at Drury Lane (John of Paris, Midas, Pizzaro, Urgana a minstrel in King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table), but she also doubled in performances at Covent Garden (Rose in Der Freischütz, Manfred, Smeaton to the Anna Bolena of Grisi in a Benefit, Catherine in Lestocq), on occasion playing one piece at each theatre.

And then, on 16 April 1835, at Old Church, St Pancras, Harriet got married. Her husband was by name John Fiddes and he gave as his profession ‘wholesale tea dealer’. He seems to have been a slippery sort of a fellow, and of little use as a husband or a businessman. However, he fathered two daughters on Harriet, [Harriet] Frederica Giovanna Fiddes (b 21 Beaufoy Crescent, 13 March 1837; d 1921) and Josephine Mariann Fiddes (b 1839; d 1923?), and appeared on a number of occasions in court on theft charges, before dying and getting out of her life.

Many a biographical note on Harriet claims that she retired at her marriage. She did nothing of the sort, even though she did take extended periods out to have her children. She returned after her marriage to Drury Lane, where in the early part of 1836 she was seen as Taolin in The Bronze Horse (‘Miss H Cawse exhibited her never-failing talent in a trifling comic part’) and as Ritta in a version of Zampa entitled The Corsair, in 1837 she returned to play Mistress Page in The Merry Wives of Windsor, Jessica in The Merchant of Venice and to deliver one of the solos in the National Anthem on Queen Victoria’s first visit to the national theatres. At the beginning of 1838, Alfred Bunn ‘loaned’ Miss Cawse to Mitchell of the Opera Buffa at the Lyceum, where she played a few performances as Cherubino to the Figaro of Bellini and the Countess of Mme Eckerlin, (‘the most perfectly sustained character in the piece was the Cherubino of Miss H Cawse. Her full liquid voice, correct intonation and arch liveliness of manner left nothing to be desired’). ‘Voi che sapete’ had been, as was traditional, borrowed by the singer playing Susanna.

Back at Drury Lane, Harriet took the role of second boy (with Miss Poole and Mrs Anderson) in the English-language premiere of The Magic Flute, played in the drama The Meltonians and created the role of Bertha in The Gipsy’s Warning (19 April 1838) and on 7 June she took a Benefit on which occasion she produced a rather feeble opera by the title of Domenica (7 June 1838). Miss Rainforth played the heroine, and Harriet teamed with Mr Compton in the soubrette role.

Domenica and The Benefit marked the end of Harriet’s career at Covent Garden, but not of her career as such. In 1839, she was announced to join the company at the St James’s Theatre, but when she reappeared it was on the concert platform. During the season she sang in the Concert of Ancient Music, with the Choral Harmonists, at the Covent Garden Fund concert, and at various personal concerts, and in the latter part of the year she went out with a Richard Carte sponsored concert party tour, alongside Charlott Ann Birch and the tenor Hobbs, during which she purveyed anything from Parry’s ‘The Inchcape Bell’ (‘with much pathos and feeling ... a fine contralto’) to a performance of The Creation. She continued to make concert appearance in 1841, and in 1842 and 1845 (16 May) she mounted further concerts of her own, but now she settled largely into teaching singing from her home at 2 Radnor Place in Gloucester Park, and at Mrs F Young’s Establishment for Young Ladies.

However, it was not over. In 1851 she made what was ridiculously claimed as ‘her first appearance on the stage for sixteen years’ when she appeared at the Haymarket, alongside Louisa Pyne in performances of The Crown Diamonds, in the comedy Goodnight Sir, Pleasant Dreams and as Fatima in The Cadi. ’A very popular singer and considered an actress of no mean pretensions in her day ... [she] appeared to be last night in full possession of her capabilities...’

Harriet did not again take up a career in the London theatre. In 1852 she left Britain, with her daughters, and made her way to Melbourne: ‘Mrs Fiddes formerly Miss H Cawse of the theatres Royal Drury Lane and Covent Garden, the Italian Opera House and Opera Buffa, the Philharmonic and Ancient Concerts and likewise one of the choir of the Foundling Hospital begs to announce that she has just arrived from London and intends taking up residence in Melbourne for the purpose of giving lessons in singing, pianoforte, guitar and harp’

She continued, in 1853, to San Francisco, where she returned once again to the stage, singing with Anna Bishop, and toured California with a dramatic troupe, until on 6 June 1855 the three women set sail on the ship the Fanny Major, direction Australia, as part of a company of twelve under the direction of the dancer known as Lola Montes.

They performed en route at the Sandwich Islands, and arrived in Australia in September 1855, but Miss Montes’s troupe fell quickly to pieces, and Harriet and her colleagues ended up in the Australian courts suing for their unpaid wages.

Harriet and her daughters stayed some years in Australia, working in various theatres ... I spot Harriet as the colony’s first Lazarillo in Maritana (13 September 1856), playing the Nurse in Romeo and Juliet to Josephine’s Juliet … but, at some stage, she and Frederica returned to Britain, for the 1861 census sees them living in retirement in Putney.

Josephine went on to a colourful career as an actress and a writer, and to a partnership and eventual marriage (Liverpool 7 March 1863) with the actor known as Dominic Murray (otherwise Morogh, divorced 1877).

Frederica married a Mr Shaw in 1866, and Harriet lived thereafter alone in Hampstead and later in lodgings. She died in Yorkshire, where the Shaws had established themselves, in 1889 at the age of 77.

The papers noted in 1833 the presence of ‘a third Miss Cawse’ in concert at Richmond. This was the youngest Miss Cawse, Fanny Rebecca (b 4 May 1825; d 1901) who was for a while a member of the Adelphi Theatre chorus.

Another sister, Clarissa Sabina, followed her father’s profession and became a miniature artist.

Apart from the many songs which she rendered well-known in her stage performances, Harriet Cawse introduced many ballads which bore her name in publication. Amongst them, I can list such as ‘My love sails o’er the [dark] blue water (Alexander Lee/Miss Fitzroy), ‘I stood amid the glittering throng’ (Bishop/Bayley), ‘My own! O that’s the name for thee’ (Lee/T Haynes Bayley), ‘The Sea Maiden’s Song’ (G F Harris), ‘Sly Cupid’ (T Latour/Augustine Wade), ‘The Motherless’ (G A Hodson), ‘Under the walnut tree’ (George Linley), ‘The Rosebud (Burns/J Lodge), Sterne’s Maria (V Novello) , “We met’ and ‘We parted’ (T H Severn/Haynes Bayley), &c.