SHERIDAN, Amy [HUNTLY, Sarah Bellamy] (b Westminster Rd, London 10 December 1838; d 11 Broad Street, Brighton 11 November 1878)

‘Amy Sheridan’ was something of a phenomenon. When she died, in 1878, at a Brighton boarding house, aged 39, of massive heart disease, newspapers from one end of Britain to the other carried a little, or even larger, obituary. Overseas newspapers, in countries she had never even visited, noted her passing. ‘Amy Sheridan’ had become, rather like Pauline Markham in America, a symbol. ‘The most beautiful woman on the British stage’. ‘The embodiment of glorious womanhood’. Sex on a stick. And she had a short(ish) life, but apparently a decidedly gay (in the C19th sense of the word) one.

Amy (we will call her ‘Amy’, short for Bellamy) was a creature of London’s high life, high night life. And maybe more. A snide little paper called Reynolds’ Newspaper took, in the mid-1870s, to making very broad allusions to Amy’s private life, which, amazingly, no one seemed to have done before. Yes, she was seen on the arm of this gentleman or that, towering above him in her furs on many a glamorous evening – Emily Soldene pictures her thus – but there was no visible husband, no steady, no Duke, no Rothschild … well, if there were such a mention, I hadn’t found it. Until I came upon a campy piece, written near the end of her life, in the said Reynolds. The Prince of Wales needed attendants for a trip East. Mr Reynolds suggested Amy, Lardy Wilson .. ‘so appreciated by the royal family’. Not once, but several times. The Princess of Wales was visiting lordly friends in Scotland. ‘Where was Amy Sheridan?’ he questioned in print.

And Lardy Wilson. Emily Soldene and Clement Scott, in my (ex-his) annotated copy of Emily’s Recollections confirm that she was the mistress of Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, and the mother of his child. So, to speak of Amy in the same phrase clearly suggests that she was a royal mistress, too. So maybe she was.

She didn’t start off as anything royal at all. She was born Sarah Bellamy Huntly (no ‘e’) in London’s Westminster Road, where her father, Matthew Huntly (1796-1872), operated as a ‘van proprietor’ (later ‘coal dealer’ and 'carman’). Mama was Elizabeth née Bellamy, and she had three brothers, two sisters … They are all visible in the censi of 1841 and 1851 in Oakley Road, Lambeth, but, by 1861, mum and dad are alone in Waterloo Rd, the kids have flown the nest, and I can’t find the grown-up ‘Amy’ anywhere. Which is sad, because I’d like to know what a 6-foot (?) blonde of hour glass proportions did, for a job, before she broke into the theatre, at a decidedly leisurely rate, in her twenties.

One thing she apparently did was take lessons. The actress Mrs Charles Selby had set herself up as a teacher of young ladies ambitioning the stage. Many answered the call – most famously the jolly Misses ‘Pelham’ who backed and premiered the soon-to-be-celebrated Ixion– and one of those was Sarah Huntly. I imagine it was at this stage that she became ‘Amy Sheridan’. An obituary says that she made her first stage appearance at the St James’s Theatre in an amateur production of the popular comedy A Game of Romps, but this I cannot find, and I propose the 5 August 1861 as her ‘debut’. The occasion was the Benefit of Mrs Selby at the Strand Theatre and the lady took the opportunity to give some of her gals a chance, of one sort and another, on a real stage, on the same programme as such established performers as Marie Wilton, Patty Josephs, Eleanor Bufton and Walter Tilbury. ‘Miss H Henry’ got the plum: she was allowed to play Lady Teazle in two scenes from A School for Scandal, while the Misses Amy Sheridan, Stella Vivian (oh dear, Mrs Selby, couldn’t you do better than that?) and Miss G Denford got to support Mrs S and Lavvy Lavine, in the petite comedietta Married Daughters.

Mrs Selby’s strike rate was pretty feeble. None of the others were heard of again. But Amy? Six foot, gorgeous and blonde? She had to be usable for something. Still, nobody leaped. It isn’t until 15 March 1863 that I spy Amy on stage again, and, yes, this time it’s at the St James’s Theatre. Under the management of Frank Matthews.

Amy was cast in Deaf as a Post, the successful old comedietta from the Haymarket Theatre, which was played as an afterpiece to the new, and ragingly successful, drama Lady Audley’s Secret. Sam Johnson, Gaston Murray, Charles Fenton, Ada Dyas and Patty Josephs played with the beginner, until the piece was replaced by The Two Gregories, in which she also featured. In May, when Mrs Selby felt the need of another Benefit, this time at the Princess’s, Amy was promoted to Mrs Candour in The School for Scandal. ‘She has appeared several times at the St James’s Theatre and given every satisfaction’, noted the press. In March A Game of Romps became the afterpiece, and one can assume this was the obituary’s false ‘first performance’.

After Whitsun, the St James’s revived the burlesque Perdita, or the Royal Milkmaid, with Patty Josephs and Adeline Cottrell, to supplement Lady Audley, and Miss Sheridan had, seemingly, her first taste of burlesque.

Why and wherefore had Sarah chosen her nom de théâtre? Or Mrs Selby chosen it for her. There were, during her lifetime, at least two other ‘Amy Sheridan’s active in music and theatre: the first in England, a minor contralto vocalist with the National Choral Society, the other, a vaudeville player in America. Of course, our Amy eclipsed the other two (or more) right into outer darkness, but I assure you, if you see ‘Amy Sheridan’ singing Elijah at Exeter Hall it is not Sarah. To start with, our Amy was just a fair vocalist and, as one journalist commented, she had a high voice rather like a peacock or a guinea hen.

From the St James’s, Amy moved on to Horace Wigan’s Olympic Theatre where, on Whit Monday, she opened, playing the role of Charity, one of the seven daughters of ‘Sense’, in Tom Taylor’s curious ‘Morality’, Sense and Sensation. The piece was not liked, although Amy and Kate Ranoe were, as newcomers, singled out for some mention (‘the graceful winning style of Miss Sheridan made her embodiment of Charity one of the marked features of the piece’).

|

| Cupid and Psyche |

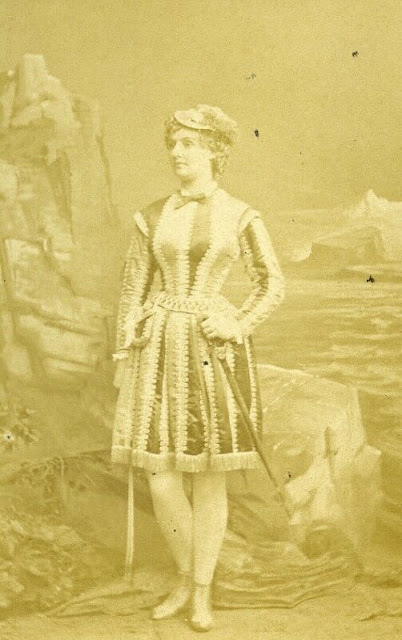

Amy was to spend three years at the Olympic, playing dashing young widows in comedy and boys in burlesque, in pieces such as The Girl I Left Behind Me, My Wife’s Bonnet, Always Intended (Mrs Mowbray), The Ticket of leave man (Emily St Evremonde), Dearest Mama, The Quiet Family, The Atrocious Criminal (Mamie van Rosen ‘the perfect realisation of a gay, young and handsome widow’), Human Nature, Fanchon the Cricket (Madelon) and the extravaganzas Cupid and Psyche (Mars), Glaucus (Proteus), Prince Camaralzaman (Queen Maimouné, later Badoura), Princess Primrose (Turfi), a hash-up of the opéra-bouffe Barbe-bleue (Prince Saphir), et ceterae. Her notices were usually short, sometime good, never really bad: she was a fair and attractive member of the Olympic company. The press was, seemingly, more interested in who, of she and Annie Collinson, was the tallest of London’s burlesque actresses.

In October, she visited the Adelphi Theatre for a rather preposterous piece entitled Maud’s Peril, before moving on to Covent Garden, where she was to play Robin Hood in the pantomime, The Babes in the Wood, and then to the mecca of burlesque, the Strand Theatre. Her first two roles were in the 1-act comedietta Sisterly Service (Rosalie de Valmont) and in the burlesque The Field of the Cloth of Gold (Duke of Suffolk ‘shows all the graces of her figure and obtains a large share of the plaudits’), starring Lydia Thompson. Both pieces had long and successful runs. Finally, at Easter 1869, The Field of the Cloth of Gold was replaced by Brough’s Joan of Arc, with Amy in another ‘darling of the ladies’ role as Lionel an esquire, then, after more Field of the Cloth of Gold, in October, by Ino (Chromos).

She appeared at Easter 1870, at the Globe Theatre, as Charles in Robert Macaire and ‘had a reception which suggestively indicated the intimacy of her relations with the public. She was charmingly attired (if that is the correct word) as Charles; wearing a bewitching hat with bewitching perkiness and carrying her hands in marvellous pockets with a swagger marvellously seductive’, and returned to the Strand once more for The Idle Prentice to a similar reaction: ‘Miss Sheridan, who always shines to most advantage when she has little else to do than to dress smartly, is a passable Sir Rowland’. She ‘looks gloriously handsome in white satin. We gallantly admit the abundance of the lady’s personal attractions but take leave to observe that, even in burlesque, the characters require more intelligent rendering than can got out of a beautiful lay figure or speeches given with a careless nonchalance, that says in dumb language “I’m to be looked at, I’m too handsome to talk properly”.’

It did rather seem that Amy had given up most of her acting ambitions in favour of being London’s number one showgirl, and of the post-theatre activity that went with that title.

But in 1871, she went further. After a turn at the Alhambra as Fogfiend in A Romantic Tale, she took an engagement at Astley’s equestrian Theatre. Mazeppa was on the bill. But Amy didn’t play Mazeppa. She apparently didn't get tied to horses. A Miss Marie Henderson took that task. Amy played the second half of the bill. The title-role of the pantomime Lady Godiva. And since this was Astley’s, yes, she did ride across the stage on a gloriously caparisoned white horse, and yes, in a semblance of nudity. The advertisements insisted it was ‘beautiful and chaste’ but the public evidently came hoping that it wasn’t too chaste. The reviews agreed she ‘looked the character well’ but also that ‘she wants voice for a singer and animation for an actress at Astley's’. Amy’s nonchalant style wasn’t really right for the vast auditorium. And more than one print was found to pout that the horse acted better than the lady.

After the pantomime was over, Amy returned to the Strand (The Last of the Barons) but, then, she made what seems like a strange decision. She signed to go to America as a replacement in the new and triumphant Lydia Thompson troupe. I suppose she thought that if her old colleague, Ada Harland, could turn herself into something of a ‘name’ over there, she might too. Maybe she just wanted a holiday. But she went. America had already heard plenty about Amy. The Clipper had been paragraphing her for years, and had nominated her ‘the woman’ of the London stage. And now she was coming.

It was a disaster. She opened in one of the company’s weakest burlesques, Robin Hood, playing Richard Coeur de Lion … ‘a very tall lady…Her bust appeared well-rounded and her waist symmetrical but her limbs, though well-turned are disproportionally long … Her face is handsome, but her reading was weak and undramatic..’

When they switched to Ixion she, of course, was Venus and was abruptly summed up as having ‘little ability’. Next they complained she was ‘not up in her lines’ in Kenilworth.

I suppose she could have ‘taken’ in America. America was the same as any other country in, just as often, preferring to look rather than listen. But what America was used to was, definitely, not ‘nonchalance’. America liked big, broad performances and Amy was big only in physique. Anyway, she got the message quickly and on 3 February 1873, when the vessel Spain docked in Liverpool, Miss Sheridan was on board.

She was soon back on the stage. And after Astley’s it was that other mausoleum of the London theatre … the Alhambra! And in which show? Why, (The) Black Crook. But London’s Black Crook was altogether a better piece of musical theatre than America’s tired hotch-potch. Its libretto was based on the famous French féerie spectacle La Biche au bois and its music was freshly composed, it was cast with excellent performers and, by Easter Monday, it had already been running healthily since Christmas. At which stage, Amy was advertised to take over as ‘the Queen of the Bells’. Since there is no role of that name in the original cast, I imagine it was fabricated and inserted to feature her. Another reference has her at one stage playing the principal boy, Prince Jonquil, a third, wholly less believable, has her succeeding to the very dramatico-sung title-role played, heretofore, by patented vocalists Cornélie d’Anka and Louise Beverley.

On first night her bodice came (dear, me!) loose, and one clenched-buttocked paper remarked ‘her first costume, charming enough in its general effect, betrayed sad evidence of bad taste in its scantiness’, but others found her perfect: ‘much admired’ ‘magnificent dresses’…

As had been her wont as the Olympic and the Strand, Amy stayed on at the Alhambra, featured behind the stars of the establishment, Rose Bell and/or Kate Santley, as Orestes in La Belle Hélène, Spalatro in Don Juan, Belfort in La Jolie Parfumeuse, Picknick in The Demon’s Bride, through till late 1874. Quite what she did, as all these musical-theatre boys, is hard to establish. She doesn’t seem to have sung much, or danced much, or even spoken an awful lot. As the reviewer had said, all those years ago, it did seem to have become a case of being looked at rather than being listened to.

It was murmured that Amy was wealthy. Maybe because of the diamonds and the furs from unnamed admirers, or just one super-wealthy admirer. But I can’t find any reference, except for those hints about the Prince of Wales, to who he, or they, might have been. Emily Soldene, in her superb memoirs, ‘outs’ all sorts of folk but concerning Amy she is (as she knew how well to be) coyly unspecific. Was that because there was no one ‘regular’, or because that ‘regular’ was too mighty to ‘out’, even for the queen of opéra-bouffe?

|

| Nonchalant, I? |

Well, she either had some money or access to someone else’s because, in November 1874, Amy Sheridan (or someone in her name) took the Opera-Comique Theatre and there produced a new version of Ixion. She brought in Richard Temple to stage the piece and play, she (or he) hired a fine cast, topped by the splendid Patti Laverne in the title-role, Louise Beverley, Temple as Pluto and lots and lots of nymphets in gauzy fragments. Amy, of course, was Venus as whom she ‘had little to do but to look handsome and commanding’.

The production apparently went rather further than before in the scantiness of the ladies’ costumes and roused a few would-be-witty paragraphs in the press, but it lacked nothing in stage design and its worst crime seems to have been a large degree of under-rehearsal. The Saturday Review lead the anti-Amys, the audiences were thin, and the whole exercise came to bits on 15 January. The moral minority cheered that it was the ‘state of undress’ that had caused the failure. I think, perhaps, more likely it was inexperienced management. Anyway, Amy ended up in court sued by the property maker for the manufacture of Venus’s car, in which Amy had made her sensational entrance. I daresay he was paid. Amy didn’t even turn up to answer the case.

And Reynolds’ Newspaper continued: ‘Disraeli wants some half dozen of his followers created peers … he has positively refused creating Amy Sheridan, Lardy Wilson and Cornélie d’Anka peeresses in their own right, notwithstanding the high favour these ladies are held in by certain members of the royal family …’. Amy first … 'the royal family'?

Amy doesn’t seem to have ventured on stage again until the pantomime season, when she appeared at Park Theatre playing the Queen of the Green Ants in Sinbad, alongside Lizzie Robson, Rose Lee and Harry Moxon. She caused a few eyes to widen when she, then, played the part of an Irish peasant woman in The Fairy Circle, but she did not take up 'acting' again.

In fact, from this time onward, her name appeared rather in the gossip columns than in the theatre ones. ‘Miss Amy Sheridan takes a dip in the Thames’. She slipped while getting into a boat. By the time the papers had finished, she had all but drowned and been saved by a gentleman from Staines, whom she subsequently married …

She didn’t. Amy never married. I don’t doubt that, if she were not Mrs Arthur Preston in law, she was de facto. But how long had he been in the picture? Was he a beard for the undefined royal, or was he a successor? We have a little, somewhat biased, picture of him which made the press (‘Miss Amy Sheridan and the stockbroker’) when he was sued for some monies owing. The picture was of a ‘brillant oisif’ who spent half his time on the river, the rest in homes in Regent’s Park and Chertsey, and who only worked when the urge came upon him. The rather strange Mr Beal of (briefly?) 46 Queen Victoria Street, City, who sued him seemed to know quite a bit about him. And about Amy. He referred to Arthur as a man ‘who could afford to keep Miss Amy Sheridan…’.

Regent’s Park? Amy’s permanent address for the last few years had been 50 Albert Street, Regent’s Park. Or Camden Town. Her house or his? In 1871 it was occupied by a Baroness Karl von Lippmann and her two infants …

He didn’t keep her for very long, it seems. In late 1878, she (or they) went to spend time at Brighton. They/she didn’t stay in a hotel, but lodged in the boarding house of a Miss Matilda Morganti, in Broad Street. And there Amy was taken with chest pains. The doctor was called but she died, as he later explained after the autopsy, from massive heart disease and internal bleeding.

Amy’s remains were buried in the Brighton Parochial Cemetery. Preston (‘husband’) led the cortège … and then vanished again into oblivion. Amy left a will. A will, at 39? She must have had a lot to leave. Her will was executed by her brother, not Preston. She left less than one hundred pounds. Odd. The contents of Albert Street were auctioned off …

Amy Sheridan was a phenomenon. The photos that remain of her range from the glorious to the what-was-all-the-fuss-about. But, of course, ideals of female beauty have changed. Today's scrawny, painted, dyed Californian beach babes wouldn’t have got a second glance in Victorian times.

But she leaves the odd question too, this striking but mildly talented lass. Was Reynolds’ Newspaper right? But would a royal concubine live in Albert Street? And just who was ‘Arthur Preston’?

Anyway, as I said. ‘A short life, but a gay one’.

No comments:

Post a Comment