CAMPBELL, S C [COAN, [Abra(ha)m] Sherwood] (b New Guildford, Conn 15 May 1829; d Chicago 25 November 1874)

One of the most notable American baritone singers of his time, ‘Sher’ Campbell had a career cast in two halves – the first in minstrelsy and the second in opera.

This makes it all the more odd that even some of the better American reference works get his name wrong. His surname was Coan. He was the son of Abr(ah)am Coan and his wife Eunice née Cooke (d New Haven 28 May 1859) of New Guildford, Conn. He was not ‘Sherman Cohen’, or anything Cohen, and he was not born ‘Sherry Campbell’.

The ‘Campbell’ came about when, aged nineteen, he stopped being a coach-trimmer, and became a professional vocalist. Now, tracking down members of early minstrel troupes, in the 1840s, is not easy. The troupes changed members frequently, and often the names of the players aren’t even mentioned. However, several diligent researchers of the past have more or less successfully collated the personnel of the rightly-named ‘only American theatrical genus’, under titles such as Burnt Corks and Tambourines, Monarchs of Minstrelsy et al. And in ‘Sher’s case, he was the subject of a very long and detailed obituary in the Clipper newspaper (reprinted in Britain’s Era) which gives every appearance of exactitude. Though, of course, they don’t quite agree, and they skate over certain parts … Still, the Clipper is, I think, pretty correct in its storyline, even if not in its dates.

So, to summarise: Sher was an amateur teenaged singer. One night, he attended a concert by the group known as George A Kimberly’s Campbell Minstrels and went, with his friends, afterwards to ‘serenade’ the singers. An audition for an audition. He was duly noticed by J A Herman, the tenor of the group, auditioned the next day and offered a job. Which his mother wouldn’t let him take. Why his mother, I don’t know: his father was very much alive in 1848, but an 1847 directory shows that Mrs Coan was running 109 State, their home, as a boarding house and father has no job. An invalid, maybe? He can be seen, again, with wife and four children but still no job, in the 1850 census. When Sher is still listed as a carriage-maker. Well, he was certainly, by this time, only a part-time carriage-maker, at best. Mother, says the Clipper, reversed her decision when a New York season was mooted and, in 1849, Sher joined up.

I don’t know precisely when Mr Kimberly started up his troupe. At one stage he claimed that it was 4 July 1840, and that it was the oldest group of its kind. Well, Campbell’s Minstrels ‘one of the oldest …’, run by Mr A Kemball, was going earlier … but at another stage, in 1854, Kimberly claimed he’d been touring six years. Which is pretty surely right. I spot him in Newark in March 1848. And my friend Betsy has dug up an advertisement in the New London Weekly Chronicle (Conn) for Campbell's Minstrels giving a performance at Washington Hall on June 14 1848. Part of it reads, ‘The Manager respectfully announces that since his last visit to New London, he has made several important changes in the company, and at a great expense, has added Messrs S C Campbell, I Howard, and S A Wells, formerly connected with the [J A] Dumbolton Serenaders, and more recently with the celebrated Christy's Minstrels, making the company complete in every particular...’.

The New York season, at Barnum's American Museum, 348 Broadway, began 31 July 1848 and they ran at various venues till the end of October … so I guess this is the season the Clipper means, and it seems Sher had been four months a member of the troupe by then, along with Bob White, Luke West, Matt Peel, J A Herman, A H Barry, Lewis Burdett, Jacob Burdett, Charles Abbott and L H V Crosby.

Subsequently, in 1850, West and Peel (‘the nucleus and main attraction of the original Campbell Minstrels’), occasionally with Joe Murphy, put together a new troupe, and S C Campbell went with them. In 1852 Abbott’s song ‘The Colored Orphan Boy’ was published ‘sung by S C Campbell of Campbell’s Minstrels’.

There is a tale told that Catherine Hayes heard Sher, and invited him to sing at one of her concerts. His ‘Dermot Asthore’ encouraged her to urge him to train for the opera. Well, Miss Hayes was playing Melbourne while the Minstrels were at Coppin's Olympic, and it is recorded that she did go to a Backus show, their 'Farewell Concert' at the Royal Victoria Theatre in Hobart, on 28 January 1856. She would have heard Sher give ‘Melinda May’, ‘Down the River’, and his imitations of a cornet. And she did give a concert the next night, performing the entire Lucia di Lammermoor mad scene. And the next night the Minstrels played their last night. Sher sang ‘Ben Bolt’, ‘Poor Old Jeff’, ‘We come from the hills’ (the Tyrolean Echo Song) and a bit of La Sonnambula. Miss Hayes’s concert was reviewed in minute detail: the support vocalists were reported as being John Gregg and Charles Lyall. So … did he or didn’t he?

The next few years were spent in and out of San Francisco, and ‘the favourite ballad singer and musical director’ of the San Francisco Minstrel troupe had the good fortune not to embark with others of the troupe on the Central America for New York in 1856. The ship sank, but Billy Birch and Sam Wells were saved. In 1859, he joined up with George Christy and R M Hooley, and, when those two dissolved partnership, he took over Christy’s share of the management for the nonce. His final engagement in the world of burnt cork was with Dan Bryant.

In 1862-3, he appeared in concert at Lafayette Harrison’s Irving Hall, where he shared a platform with Elena d’Angri, Gustavus Geary and with another transfuge from the minstrel world, best friend William Castle (aka J C Reeves). The two men also sang in Gottschalk’s concerts under Pedro de Abella (Mr d’Angri). Castle was Abella’s pupil. I imagine that Campbell was too.

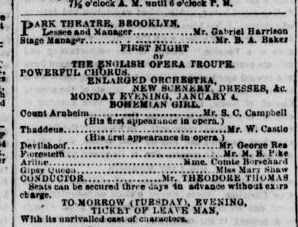

4 January 1864 marked the beginning of Campbell’s operatic career. Gabriel Harrison of Brooklyn’s Park Theatre (and brother to Lafayette of Irving Hall) who had been giving matinées musicales with some success, mounted The Bohemian Girl at his Brooklyn headquarters. The experienced Marie Comte-Borchardt took the role of Arline, Castle was Thaddeus and Campbell played Arnheim. George Rea and Mary Shaw of the stock company supported. The production transferred to Niblo’s Gardens, as ‘the New York English Opera Company’ and there ‘subsisted for two months on The Bohemian Girl and Maritana … a motley but very pleasant crew’. The Gipsy Queen was now played by ‘Miss [Louisa] Myers, the poetry reader’. And the Devilshoof died.

Lafayette Harrison (‘the Harrison English Opera Troupe’) took the company on the road, with an improved personnel -- Edward Seguin as the new Devilshoof and Jenny Twitchell Kempson sometimes, now, as the Queen – with the two operas, and on 4 May at Philadelphia produced a third: J B Fry’s Notre Dame de Paris. Campbell played Frollo, Seguin was Quasimodo and Mme Borchardt the gipsy. Slowly, the company began to grow. Fra Diavolo was added to the repertoire, and 4 July a new New York season was opened at the Olympic Theatre, where The Rose of Castille was included in the programme for the first time. Campbell played Don Pedro. But the enterprise ended in financial failure.

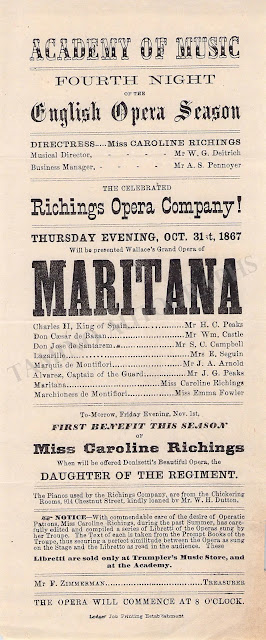

Our baritone and tenor, however, took up the reins themselves, and soon after the closure, they put out a company of their own with Fannie Stockton, Walter Birch [eig Smith], Georgie Fowler, John Clark (‘Brocolini’ to be), William Skaats and Warren White, and musical director Anton Reiff, playing Faust, Lurline, The Lily of Killarney, The Bohemian Girl, La Sonnambula and The Rose of Castille.

|

| Fannie Stockton |

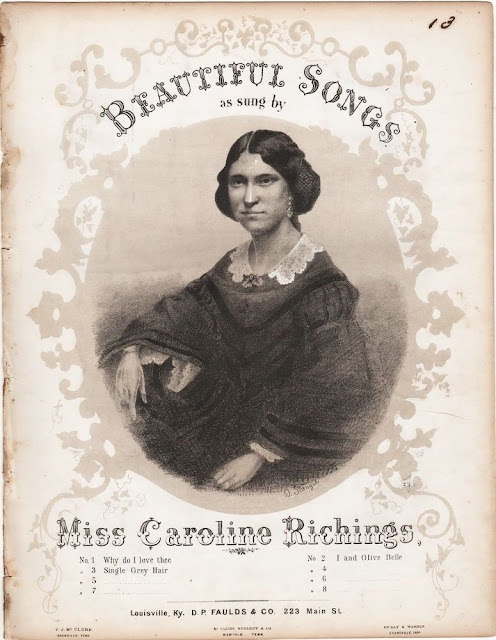

Life was easier with the Rosa company. Madame Rosa brought with her a baritone of her own, the highly capable, English ‘Alberto Laurence’. And ‘Alberto’ would stay in America, to share and, indeed, take the place of Campbell as the English opera’s most skilled baritone, before becoming one of New York’s top singing teachers. They shared the baritone roles in the Rosa repertoire for two seasons, and when Mme Rosa was not there, Caroline Richings came back on the scene to keep things going. Later, Tom Aynsley Cook was part of the company, and even Charles Santley played some performances, so baritone of class were not lacking.

Among the roles which Sher Campbell played with the Rosa company, and its temporary remake as C D Hess’s troupe, were Colonel Wolf in The Puritan’s Daughter (with Laurence as Clifford), Arimanes in Satanella, Figaro in The Marriage of Figaro (Laurence was Almaviva), the title-role in Don Giovanni, Caspar in Der Freischütz, Plunkett in Martha, Arnheim in The Bohemian Girl and Beppo in Fra Diavolo into which he interpolated a solo ‘Let all obey’ manufactured from a piece of Poliuto and usually popped into The Enchantress. Laurence, however, was clearly considered the senior, and Cook and Henri Drayton took their share of the spoils.

Dwight’s Journal of Music summed up in 1870, after praises of Laurence: ‘Campbell, too, has improved, using his beautiful voice with very little of the unpleasant nasal element of which I complained last year, He also shows more ease of action, although I will adhere to my opinion that nature intended him for a Presbyterian preacher…’. Another paper found Laurence ‘too English’ and much preferred Campbell.

When Rosa and his wife returned to Britain, with the project of launching their opera company there, Mr Campbell and Mr Castle went too. They sailed for Europe 9 July 1872, allegedly going to Milan. I don’t know whether they went. At one stage, they were to be seen in Egypt, with Parepa, ‘for their health’. I think the health problems were, probably, both Parepa’s and Campbell’s … they each had little time to live.

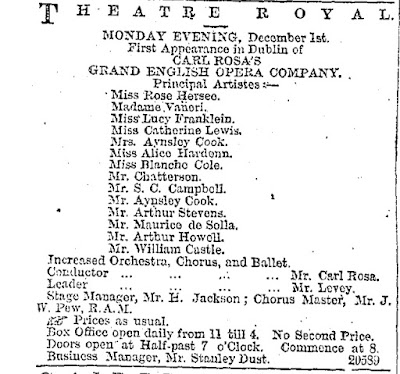

Parepa was too unwell to play with the company bearing her name when it opened in Manchester on 2 September 1873, but Campbell was there, along with Aynsley Cook and the young Arthur Stevens (bass). However, Sher was still in his second bass-baritone spot. Rosa had hired a certain Francesco Mottino, a veritable Italian with good English, to replace Alberto Laurence in the main roles. However, the said Signor Mottino was in no way the equal of Alberto Laurence, and soon he was gone, leaving Campbell and Cook to share the bass-baritone roles. Campbell was Figaro, Don Giovanni, Arnheim, Mephistopheles, Rodolfo, Beppo (still with his extra song), Don Pedro … through Bradford, Sheffield, Bristol, Bath, Dublin, Cork, Limerick … the bulk of the initial tour of what would become England’s longest-lived English opera company.

His last performance was as Mephistopheles, on 31 January 1874, after which the company closed down. Madame Rosa had died some weeks before.

On 25 May 1874 the two men arrived back in America, together, on the ship Spain. Sher was engaged for the forthcoming tour of Clara Louise Kellogg’s company. He made it to the rehearsal venue, in Chicago … but he was ‘failing with chronic bronchitis’, caught a cold, and died there of ‘dropsy and a liver complaint’. The press reported 'His voice was fine, and his face expressive, but as for his figure, it was faultless'. A veritable barihunk.