.

It has been a delightful work week. I've had even more interesting queries than usual come across my desk, all sorts of different musical and theatrical topics which need a little more clarification to help clear away the incomprehensions and misunderstandings which litter 'history' as we've been lazily led to accept it. This wee article has sprung from a chat I had, a few days ago, with an American colleague, during the course of which the topic of -- guess what? -- the jolly old Black Crook came up.

No, I'm not going to pontificate about C19th America's most enduring pasticcio legshow, again, I promise. But we got on to the subject of the music which decorated the piece. Whence it had come, and how much of it, if any, was original, and how much, if any, had survived. Well, we know that Balfe's famous 'The Power of Love' (Satanella) and Lurline's 'Flow on, Silver Rhine' were used, I've told before the story of the 'Naughty Men'. The songs in a féerie were traditionally second-hand: especially in their music. But what interested me was that query that Doug raised 'had any of the dance music come from Paris'? I had always assumed, since the ballets were not credited to any composer, that they would have been, in the regular French fashion, the original work of Thomas Baker, the musical director. Well, to cut out any persiflage, after a little scouting, I still think they, very probably, were. They were certainly published (in various arrangements) under his name. But, anyway, the off-chance that anything French had been infiltrated into the pasticco, led me to delve a little into féerie things French and there I got hooked on to a slightly different topic. La Biche au bois.

La Biche au bois is one of the most famous of the great Parisian féerie spectaculars of the second Empire, when the genre and the Paris stage was at its great peak. Or one of them. Its story, taken from the Countess d'Aulnoy's amazingly inventive collection of fairytales, begins as that fairy-christening-cum-Carabosse plot which the English-speaking world knows as The Sleeping Beauty.

Then, the 'opening' having established who was who, it dissolved, more or less, into a series of songs and scenery, of choruses and of ballets, while taking care, in its libretto, always to keep its plot thread -- Prince in search of Princess -- alive. I've just re-read the libretto

https://archive.org/details/labicheauboiso00cogn/page/n3

and I reckon that it stands up really well, 170 years on. Except that, given the womanpower required, it could never be produced today. Anyway, the Prince in order to find his Princess (who hasn't fallen asleep, merely been transformed into a doe), has to fight his way in traditional fashion, through all sorts of extravagant masterpieces of scene-painters and stage-mechanic's art, against some stunning nasties, accompanied by much song and dance, and that makes up the evening's entertainment.

Well, a book could be written about the tale of 'The Hind in the Wood' and its various mutations (notably an unloved one of 1826) into all sorts of theatre pieces, but that's for another time. Doug's query was still in my head. What exactly was (as far as can be redeemed today) the music which was sung and danced in this famous spectacular when its most memorable production was first put on the stage, in 1845, at Paris's Théâtre de la Porte St Martin?

The credits tell us that the large score was 'arranged and composed by Auguste Pilati'. 'Arranged and composed', of course, always meant -- in the style best-known to Englishfok today through The Beggar's Opera -- that the songs used pre-loved tunes (known as ponts-neufs) adapted to, usually, new and sometimes even relevant lyrics. Often with their melodies briefly acknowledged in the published libretti in a partially (today) puzzling way. So preambule over: here is the score of the 1845 La Biche au bois, as far (pretty far!) as I've been able to decipher it. With illustrations not always of 1845. The show stayed around for a long, long time.

ACT I

TABLEAU ONE

Scene one: (1) Opening Chorus by Pilati

Scene two: (2) Solo King Drelindindin to the tune of the song 'Un homme pour faire un tableau', originally sung by Vertpré in the 1-act comedy Les Hasards de la guerre (Théâtre du Vaudeville 1802), written by 'citizen Maurice' and according to the critic containing 'quelques couplets heureux'. That was putting it mildly. This tune, written by the prolific Joseph-Denis Doche, became one of the most popular ponts-neufs of the times, used over and over again in musical pieces.

(3) Chorus to the music of the Clochette de la Pagode from Auber's Le Cheval de Bronze. Used also in La Poudre de Perlinpinpin and a number of other pieces.

Scene three: (4a/b) Chorus to the music of La Valse de Greenwich and the Galop des Servantes from von Flotow's ballet music for Lady Henriette, ou La servante de Greenwich

(5) BALLET: Pas des Sonnettes or Clochettes. Music uncredited, but affirmed to be by Pilati.

Scene five: (6) Chorus to music from Auber's opera Le Serment

TABLEAU TWO (THE YELLOW KINGDOM)

Scene one: (7) Solo for Fanfreluche (formerly Becafigue), the Prince's esquire. 'Il faut avoir perdu l'esprit'. This tune had already been used by the authors/producers in their féerie La Fille de l'air. I see it thus-titled, also, in a piece called La Baronne de Pichina. And if we dig up the text of La Fille de l'air, we discover that the melody is that of the highly popular song 'En verité, je vous le dis' by the chansonnier Frédéric Bérat, which had, in its unadapted form, been used in other vaudevilles (La Canaille, La Mère Gigogne which also used 'Le Trois Couleurs', Serment d'amoureux, Un vieux de la vieille roche) ... as well as having its tune reset to words by other well-known lyricists

Scene two (8a) Solo Prince Souci 'Le Point de Jour'. A not unfamiliar phrase, but almost certainly the popular piece composed by Nicolas Dalayrac and first sung by Mons Martin in his opera Gulistan, ou la Hullah de Samarcand.

Scene two (8a) Solo Prince Souci 'Le Point de Jour'. A not unfamiliar phrase, but almost certainly the popular piece composed by Nicolas Dalayrac and first sung by Mons Martin in his opera Gulistan, ou la Hullah de Samarcand.

(8b) a second solo for the Prince based on the romance 'La Peur' aka 'Ne me regardez pas ainsi' music by Albert Grisar

|

| Grisar |

|

| Gabriel as Prince Souci |

Scene three: (9) Solo Prince Souci: 'Les Trois couleurs'. A all too familiar phrase of the era upon which many a Napoleonic 'patriotic'/propaganda song was built. Vide: the famous poem of Béranger. I see one song-tune thus named used in L'Hôtel des haricots in 1837. And in Le Lion et le rat in 1840. Which maybe the one penned by Adolphe Vogel in 1830. Or not. But whichever tune is referred to, it was used and reused in vaudevilles, and elsewhere, by motivated musicians.

(10) Ensemble on music from Balfe's opera Les Puits d'amour

Scene four: (11) Chorus on air from Act I of Gulistan (Dalayrac)

Scene five: (12) ensemble: Aika, Prince and Queen Jonquille on Flotow's air as used in the second act finale of Iwan le Moujick. The only music credited to Flotow in Iwan is noted as being 'no 4 de la musique nouvelle'. The second act finale is noted as being 'from Lucia'. Which is surely Donizetti. Or Carafa. Bit puzzled by this.

|

| Louise Maigny as Jonquille (1865 revival) |

TABLEAU THREE (THE FAIRY OF THE SPRING). Otherwise Fairy Crab. Here come the baddies. Sadly, she doesn't sing.

TABLEAU FOUR (THE DARK TOWER)

Scene one: (13) Solo Desirée 'Oui, je veux voir le ciel et la montagne' to a tune by Hippolyte Monpou

(14) Ensemble Desirée and Giroflée to a melody entitled 'Roi des Hirondelles' which I have not tracked down

Scene two: (15) Ensemble: Giroflée and Pélican to the tune known as 'Prends-garde à ta marotte'. I don't know who composed this melody, nor when, but it was sung by Adèle Pernon in the title-role of a Cogniard musical comedy entitled Le Fils de Triboulet (1835). Even then, it was not new. It had ?begun life under the title 'Ou donc est, je vous en prie' in the pasticcio vaudeville Judith et Holopherne (1834, Palais Royal), where it was sung by Mlle Déjazet. Whereas all the other numbers are credited, this one is not. It was also used in Iwan le moujick, when the tune's alternative title was given as 'Prends bien garde à ton nez'.

Scene five: (16) Chorus on a piece from Donizetti's Parisina. The same piece had already been used in the Cogniard piece Les Trois Quenouilles (1839).

(17) Ensemble Desiree, Fanfreluche and chorus based on the Air de Bengali from La Planteur by Monpou. Once again, this piece had already served as a solo for Achard in La Fille de l'air.

TABLEAU FIVE (THE SYCAMORE FOREST)

ACT II

TABLEAU SIX (MOTHER GOOSE)

Scene one: (18) Mother Goose's song, to a melody by Henri Potier

Scene three: (19) Hunter's chorus to the tune of 'La Saint-Hubert' by Jullien

Scene four: (20) ensemble Mother Goose and Fanfreluche to a tune (unknown to me) 'Paris à l'eau'

Scene five: (21) Solo Giroflée. To the music of the famous romance entitled 'Les Yeux d'une mère, ou huit ans d'absence' by the popular songwriter (and specialist in 'mother' songs), Loïsa Puget, and popularised by Elisa Iweins-d'Hennin in the nation's concert rooms. Previously used, prominently, by the Cogniards in Iwan le moujick as a duet for hero and heroine.

Scene six: (22) Solo Prince to the tune of 'Ange de bonheur'. This would appear to be the ballad of that title composed by Joseph Vimeux

TABLEAU SEVEN (THE CENTRE OF THE EARTH)

Scene one (23) trio Giroflée, Fanfreluche, Prince to the tune of 'De tous les maux ici-bas' which appears to have been another hardy annual. It had been used in La Fille de l'air (1837), and it was used in 1820, in a vaudeville titled L'Ermite de Saint-Avelle, when, although the music was declared to be 'by' Guiseppe Louis Ballochi, it was attributed to J D Doche. The score of this piece is in the Sorbonne if anyone would like to check.

(24) Ensemble composed by Pilati

Scene one (25) Chorus to the same tune as (24)

(26) Ensemble Desirée, Giroflée based on an air, seemingly sung by Déjazet, in the 1824 Scribe vaudeville La Haine d'une femme, ou Le jeune homme à marier. Few of the numbers in this piece are credited, but one featured one among them that is, is the finale written by Adolphe Adam. Maybe, maybe not.

(27) Solo Prince to the tune of Gatien Marcailhou's 'Valse d'Indiana' as arranged by Pilati. This waltz was on every barrel-organ, pounded out by little girls on tuneless pianos, one of those slightly showy-sounding, heavily marked pieces which scored itself into the fabric of the age ...

Scene three (28) Ensemble Prince, Fanfreluche 'Quel est-ce bruit, cette rumeur'. A piece with Napoleonic overtones which the Cogniards reused (La Cornemuse du diable and probably etc). But who actually composed it ...?

(29) Parade of the fishes (costume parade) to music from Iwan le moujick said to be composed composed by Flotow. This one is confirmed as the 'Air de Lucia'. Lucia who? Miss Lammermoor? Flotow? Bit confused here. I presume they didn't do their fishy marching to the Mad Scene. Ah, could it be the Nozze di Lammermoor of Ballochi and Carafa (1829)?

(30) Chorus of fishes set to 'La Violette', composed (1828) by Carafa, arranged by Henri Herz, rearranged by Pilati

TABLEAU TEN (THE COTTAGE OF THE INVISIBLES)

TABLEAU ELEVEN (THE TERRIFYING ROCK)

(32) Chorus, ensemble and scene music by Pilati

ACT III

|

| Gabrielle Delval as Aika (1865 revival) |

Scene one: (33) Chorus and ballet (pas de sept) arranged by Pilati on the Pas des Almées from Friedrich Burgmüller's La Péri

Scene three: (34) ensemble, King and Pélican. The music is given here as 'Les Hussards de Léonore'. I have a feeling this title is from an old tale. But the piece probably has more likely something to do with the Cogniard drama Lénore, ou les morts vont vite (1843) for which Pilati wrote a hussars' chorus.

ACT IV

TABLEAU THIRTEEN (THE KINGDOM OF VEGETABLES)

(36) Solo: Canteloup to the 'Air de Colalto', a famous melody by Henri Darondeau, featured initially in the vaudeville Un Tour de Colalto (1809) which was used in many a pasticcio score

TABLEAU FOURTEEN (THE MERMAIDS' CAVE)

(37) Solo The Mermaid arranged by Pilati from Burgmüller's ballet La Péri

(38) Pas Seul. Pas de la Syrene. Music affirmed to be by Pilati. In fact, this dance was a quasi-pas de deux, the soloist having for partner her own shadow.

|

| Hervé? Surely the 1866 revival |

TABLEAU FIFTEEN (THE ISLAND OF DELIGHTS)

(38) Chorus uncredited

(39) Duet Prince, Fanfreluche 'to a new tune' (presumably by Pilati?)

(40) Ensemble: Prince, Gambling, Temptation to an air entitled 'Rose Pompon' which could be any one of many of that name

|

| Mme St Hilaire as La Fée Topaze |

(41) BALLET of the Temptations affirmed to be by Pilati. Pas seul by Mlle Rosette (Volupté).

(42) Ensemble Prince, Fanfreluche on a melody from Ségur's 1799 piece Le Gondolier, ou Une Soirée Venitienne, music by François Foignet fils. I imagine it is the same 'Chanson du Gondolier' used for Achard's parody of Rubini in the musical comedy Iwan le moujick.

TABLEAU SIXTEEN (FAIRYLAND)

Scene music. Parade of fairytale characters, ending with La Biche au bois and the apotheosis.

A lot of music for an evening, yes? Plus four ballets, plus 46 pages of dialogue ... the Cogniards gave their public their money's worth!

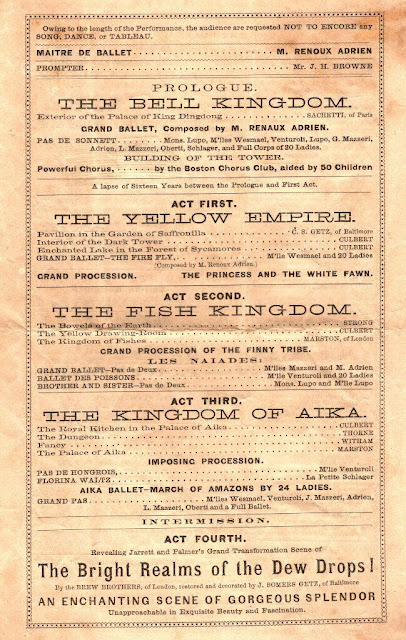

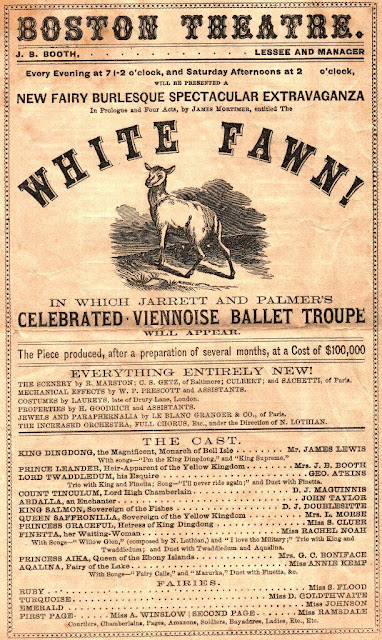

I haven't yet investigated how much of this Biche went into the making of the major revival (in 30 tableaux and 60 transformations) which was responsible for London's Black Crook, Germany's Prinzessin Hirschkuh, America's White Fawn (for which English conductor Howard Glover turfed out most of the score and popped in 'the greatest hits of Howard Glover!') and the every-increasingly vast revivals over half a century ... but I shall.

It would be fun, too, to see where the triumphant scenes -- the vegetables, the fishes, the Moorish Princess's Castle with its interpolated (later) lion act .... were used.

But for the meanwhile, I'll see how much of this music I can find in published form ... maybe the score could be at least partially reconstructed.

Ok, I'll tell you a secret. I'll tell you why I'm so fond of La Biche au bois. Many years ago, Louis Benjamin of the London Palladium mentioned, over a dinner at a famous East End restaurant, that he was thinking of staging a spectacular pantomime in the coming Christmas. Something tinkled in my brain. I remember that I said something like 'oh do make it not Aladdin or Cinderella ...'. Anyway, in the next day or two I wrote one, until the title of The Black Crook. It was, of course, a 20th century version of La Biche au Bois, with enough music and scenery and fairy costumes to break Coutts's bank ... Of course, Louis was into a run of long-running musicals and his thought of a pantomime probably didn't last more than the space of a dinner time ... but somewhere on my dwindling shelves, amongst my other attempts at playwriting, there is probably a typescript of The Black Crook ...

Well, well ... look at this .. I suppose this is what's called juvenilia ..

PS, I just found this delightful 1868 ditty composed to the stuffed 'biche' used in the production!

A la Biche empaillée qui figurait à la Porte-Saint-Martin dans La Biche au Bois

Depuis que, renonçant à vivre, La Féerie est sans picotin, Et que l'on a, comme un sot livre, Fermé la Porte-Saint-Martin, 5 On plaignit, lorsque vous partîtes, Biches et divertissement, Les choses grandes et petites Qu'abrita ce vieux monument, Les beaux trucs, les portions nues 10 De mademoiselle Delval, Frédérick marchant dans les nues Et le souvenir de Dorval, -- O théâtre que je harangue! -- Et les auteurs, que tu n'avais 15 Invités qu'à tirer la langue Devant les danses de navets!