To say precisely who were the first English dancers to perform the cancan in the English-language theatre is pretty impossible. We know that top dancers of the 1860s, such as the Morgan sisters and Esther Austin, had danced versions of it on the Continent, or at least danced in shows where the dance was on the programme. Lord knows whether Mdlle Fanchette was from Paris or Paddington. Julia Mathews was London-born, but brought up in Australia. Over in America, Lucille Tostée gave the Grande-Duchesse version (now advertised as ‘à la Mabille’) and was followed quickly by the Worrell sisters with a ‘burlesque’ version, and by Tony Pastor’s ballet ‘The Grand Cancan, or Soirée au Jardin Mabille’ which proffered a ‘polite’ version danced by Pastor and Miss Addie Le Brun. Mlle Aline Le Fevre and Johnny Manning introduced it to St Louis and one Erminie Venturole to Philadelphia. Back in Britain, J H Ryley and Marie Barnum put a particularly lively routine of the cancannish variety into their Dancing Quakers act, Esther Austin joined the Carle family in a quartet at the Canterbury Hall … and so forth and so forth. And, meanwhile, troupes of ‘French’ dancers from Huddersfield and Hartlepool began to proliferate. Australia banned a 'Mlle Thérèse' from performing her version of the cancan at Melbourne’s Variétés.

But amongst all this flurry of, often, fairly approximate cancanning, some genuine quality performances emerged. The group on which I am going to focus was acclaimedly the best of them. It was not made up of pretty ladies who really couldn’t really dance -- for the male element had slipped away, now we had four girls, two dressed as men – but made up of genuinely skilled principal dancers. Three of the English ladies from this team, the Colonna Troupe became, arguably, England’s outstanding performers in the style: Amelia Newman dite Colonna, Sarah Wright dite Mdlle Sara, and ### dite Jenny Mills. And here are their stories. Or as much of them as I have been able, after several efforts, to exhume.

AMELIA NEWHAM aka COLONNA (NEWMAN, Amelia Augusta) (b St John’s Wood, 31 December 1844; d Islington 1927).

Amelia was born into a theatrical family which would leave its traces on both sides of the Atlantic. Father, William Hill Newham (b 1 April 1815; d 15 April 1870) was an actor – at the Albert Saloon, briefly as actor-manager at the Woolwich Theatre, and then, from 1853, as a member of the company at Sara Lane’s Britannia Theatre. He remained a pillar stock actor there – his specialty being Pantaloon in the annual pantomime -- for over a quarter of a century up to his death. Mother, Maria Louisa née Brown (d 24 January 1883), followed the same profession and was long a character lady at the Britannia.

|

Father at the Britannia

|

The Newhams had nine children, nearly all of whom would make a career as dancers, pantomimists, actor, music-hall artists; no less than five of them with remarkable success. Amelia’s time in the sun may have been briefer that that of her brothers and sisters, but on her the sun shone brightest.

I spot Amelia first at Christmas 1863, dancing Columbine in the Harlequinade of E T Smith’s Astley’s Theatre pantomime,

Harlequin and Friar Bacon. She then moved to Leicester Square’s Imperial Music Hall, initially sharing the dancing duties with Celeste, alongside such dubious creatures as Mme Rudderforth from Vienna and Signor Mordini, as well as the more verifiable Cecilia Jolly, Frank Elmore and Sailor Williams. By May, she was topping the bill in the ballet

The Sultana. She was next engaged for John Douglass’s Standard Theatre, where she ‘looked and danced charmingly as the Fairy Queen in T

he Forty Thieves’. The role of Morgiana was played (‘her first appearance’) by Miss Clara Newham. Clara? Well, it could be Adela Maria (b 1843) or it could be Caroline Ann (b 1848). But I don’t see Clara when, at Christmas, Amelia is ‘a most graceful and pretty’ Columbine in

Dame Durden and her five serving maids as well as the pantomime’s choreographer. With the parents playing at the Britannia and 14 year-old brother a small acrobatic part at the Strand, the Newhams were doing nicely. But there was better to come.

|

Fred at the Strand

|

She repeated her dancing/choreographing duties in the 1865 Standard panto,

Pat a Cake, Pat a Cake, Baker’s Man, and then seemingly migrated to the Surrey. Both Miss Newham and Miss C Newham (!) can be seen playing small parts in the production of

East Lynne, behind Avonia Jones. But no! It is Adela and Caroline. Miss A Newham is still at the Standard. So it's Adela at the Surrey in

Leah (Roset), presumably as Elfie Earl in

The Jolly Dogs of London at the Britannia and with Fechter at the Lyceum at Christmas in

Rouge et noir. Young Fred played in panto at the Surrey. And Amelia? Well, she’s not at the Standard this year. It had burned down. Wherever she was, and it may very well have been Europe, she was in a state of transformation, for Miss A Newham would not be seen again. She had mutated into Mademoiselle Emilie Colonna.

Actually, I have a fair idea where she was. In the early part of 1867, Amelia produced a daughter, Amelia Sarah, and in mid-1868 a son, James Barge R. The progenitor involved was one Mr James Barge Rogers (b Southampton Place, Camberwell 6 December 1840; d St Saviour 1883), son of an independent minister, who worked as an assistant to E T Smith. The couple got round to marrying 28 February 1873.

|

Finette (Joséphine Durwend)

|

It seems to me that Mr Rogers might have been behind the mutation but, anyway, in 1867, ‘Miss Emilie Colonna’ (the name joyously taken from Disraeli’s

Lothair ‘Thou must see Colonna’) turned up as Columbine in the pantomime at the Surrey,

The Fair One with the Golden Locks, with the enigmatic Augusta Thomson in the title-role. Apparently just as Columbine. No quadrille. But that was soon changed. ‘Madame Colona’ (sic) and her troupe of French Dancers turned up next round in the pantomime,

Aladdin, at the East London Theatre, supporting no less than Emily Soldene! And as soon as that was over, they headed for the provinces with an act entitled

Les Folies des Grisettes. Theatres, music-halls, the ‘renowned French dancers’ (I don’t believe a single one of them was!) caused delicious tremors as they featured alongside Augusta Thompson in the burlesque

Cinderella at the Liverpool Prince of Wales, added

The Judgement of Venus,with Amelia as that lady,‘decidedly eclipsing Madlle Finette’ until by 1870 the

Era could describe her as ‘première danseuse characteristique of the world, with her celebrated troupe of French dancers, now at Brighton. Acknowledged by managers, press and public as the best and only dancers of the real Parisian Quadrille, ‘Le Can-Can’, that have appeared on the English stage’. ‘The dancing of this troupe is very graceful, devoid of all vulgarity and wonderfully clever’. Alas, no one chooses to tell us who the other three quadrillers were at this time, but the Misses Mills and Wright were seemingly there.

‘Among the exponents of the quaint ‘Parisian Quadrille’ Madlle Colonna’s troupe stands pre-eminent’ proclaimed the press, ‘a more lively and suggestive exhibition of the rollicking dance in which the once merry but now unhappy France was wont to delight has probably never been witnessed’, in their engagement at the Alhambra in the ballet of

Les Nations. But that engagement provoked a crisis. A cartoon of the girls performing was published in a disreputable sheet, and used as artillery by interested parties to have the Alhambra divested of its licence for dancing.

But, if the troupe, its reputation now even more sensational than before, no longer performed at the Alhambra, there were plenty other houses longing to take them in. Miss Alleyne hired them for the Globe Theatre, where they performed a ‘Gipsy Dance’ in Spanish costumes (the cancan, it was said, was descended from the Spanish cachuca), and then in the Christmas piece

The White Cat. Next, Charles Morton and Emily Soldene took them to the Philharmonic in Islington where they danced the

Grande-Duchesse finale in Soldene’s potted opéra-bouffe, and a

Chilpéric Quadrille in her short version of that piece. Paris reported ‘J’avais vu Mme Colonna et ses petites amis danser leur celèbre quadrille … Ce n’était pas de l’enthousiasme, c’etait du délire.’

They did their act at the Britannia in

The Last Night and the Last Morning and

Three Masked Men, at the Royal Alfred in

The Corsican Brothers, Deadman’s Point and

The Police of Paris, and visited Liverpool where a penny-a-liner took it on himself to risk a description of the girls as being ‘without a shred of reputation’ and accused them of ‘having the green room open till 4am, drinking and flirting’. Amelia sued for libel and won. And left for Glasgow with her team to perform the

Chilpéric Quadrille, in

Harlequin and the White Fawn.

|

Rigolboche

|

And then the troupe—now six in number -- crossed the channel to play the Folies Bergère. ‘The female Clodoches’. Paris wasn’t sure.

La Vie Parisienne mused: ‘On ne peut pas appeler ça de la danse. L’orchestre attaque le quadrille d’

Orphée aux enfers, le rideau se lève, six anglaises, peu vetûs, se precipite sur la scene et là sont aussitôt prises d’une veritable attaque de folie. La danse de Mademoiselle Rigolboche était une danse correcte et classique a côté de cette chose sans nom … C’est un fouilli de bras et de jambes ..’. Folk loved it or loathed it. ‘They had been well received but their triumph was a stormy one and, during their last nights, their lively quadrille created a perfect tumult’. Amelia stirred the fires by writing to the

Figaro.The dance had caused no problems all round England, she claimed, and blamed a cabal. And they promptly got hired for the Palais-Royal, where they did the good old

Chilpéric quadrille as part of a spectacle coupé with Chivot and Duru’s

Les Filles de Barazin, to their ‘usual stormy reception’. Next came the Pavillon de l’Horloge … while the opposition advertised ‘Mdlle Olonna’. They visited Marseille, Le Mans, played the Château d’Eau with their

Boudoir de Vénus, the Nouveautés, the Menus-Plaisirs, the Alcazar before floating home, after 231 performances, to appear at the good old Britannia in the pantomime

Tommy and Harry.

But at not yet thirty, it seems Amelia’s time in the sun was over. Maybe the cancan was no longer a novelty. Maybe she went back to Europe. I have looked and looked, but from Sheffield and Sunderland in mid-1875, onwards, I find no trace of ‘Colonna’, nor her two daughters. I find only the registration of a son, Isaac Henry born in Paris 13 December 1876, and then James Rogers’ death in 1883. In London. She apparently died in Islington aged 85 or 90.

I followed up the rest of the family. Hoping to find her. And found all sorts of other theatrical things. There is Mama Maria Louisa in the 1881 census, with her three youngest children. Adela (1843-?) and Caroline have retired from the stage, but Caroline (1848-1932) took a souvenir with her. She married corpulent comedian ‘Jovial’ Joseph Edward Colverd and gave birth to several theatricals from among her half dozen children followed by multiple grandchildren. Albert (1863-?) eschewed the stage. So did his brother Philip [Augustus] (1854-1914). But the remaining two brothers and two sisters all made a name as entertainers. Frederick [James) (1850-?) who had begun as a juvenile went on to become a pantomime clown and music-hall sketch artist. In 1909, I see him playing in a comedy troupe including one Charles Chaplin. Fred married Louise (ka Louie) Anson, who acted alongside him when not producing children.

George didn’t marry. He worked and lived all his adult life with his partner, Fred Latimar, as ‘comic and sensational duettists’, ‘the modern drawing room Belle and Swell’ (George was the Belle) and in the 20th century they made a specialty of playing Ugly Sisters in

Cinderella.

Sisters Julia (b 1857) and Rose (b 1860) found fame in America. Both as cancannish dancers. Julia had decided to call herself Violet, and the Misses Newham can be seen playing panto in Liverpool in 1877. 'Violet Newham' is the solo dancer in

The Forty Thieves at Greenwich in 1888. The pair of them crossed the Atlantic in 1889 (‘English skirt dancer and sensational high kicker’) with the unfortunate party engaged by leg-show merchant M B Leavitt. They went largely separate ways, but in the same line of girlie-show business. ‘Rose Newham’ (‘while full of grace and really remarkable, was not refined’) appeared in a number of theatre shows as a featured dancer (

Henrik Hudson, The Sea King, The Spider and the Fly, Penelope and

Columbus with Lydia Thompson,

Fantasma with the Hanlons), Violet, after a stint in the touring musical comedy

A Stuffed Dog, re-re-christened herself ‘Violet Mascotte’ and went out as the star of the farce comedy

The Corker, and of her own ‘British Burlesque Co’. Violet Mascotte’s Merry Maids or Bungalow Beauties were still on the road, playing Leavitt-type shows, under titles such as

Lady Godiva and

Cupid, in 1918, from 235 Washington Street, Braintree, Mass. She married one ‘Wilfred Chasemore’, her company manager, just as Amelia had done with hers, but I have no idea what happened to him. Rose became Mrs A M Stuart and died in New York 8 April 1905. None of them seemed to do censi or other official documents. But they all kicked!

So, lots of Newman-Newnham ends still to tie up. But we are getting there. If anyone knows what happened to Colonna (who the record seemingly show to have died in Islington in 1927, at the age of 90 (wot!), which would make her the 68 year-old 'domestic' in Brixton in 1911?), her children, ‘Violet Mascotte’ …?

SARA [WRIGHT, Sarah Jane] (b North Street, Lambeth, x 3 September 1854; d Kingston-upon-Thames 6 July 1902)

I’ve written a lot about ‘Sara’ before, because she was, for much of her eccentric career the solo dancer with and a great feature of Emily Soldene’s company. Other people have written about her too, but mostly only about her extravagantly high kicking and the resultant brushes with the licensing authorities.

Sara came from a rather different ‘showbiz’ background to that of Amelia. Her father, George Wright, was a waiter at the Canterbury Music Hall, and the child Sarah was, from a young age, a dancer in the troupe organized there by Madame Louise. ‘A wispy slip of a girl’. Alas, Amelia didn’t advertise the names of her co-dancers, so I don’t know when Sarah joined up, but she was a 16-year-old part of the Colonna troupe at the Alhambra in 1870 when the house’s license was withdrawn, and it was her high kicking which has gone down in history as the reason – or the excuse.

In 1871, Sara ‘late of the Colonna Troupe’ joined Charles Morton and Emily Soldene at the Philharmonic Theatre, Islington. Madame Soldene gave her her new name, and teamed her with the skilled Lily Wilford, Charlotte White (formerly of the Living Marionette child show) and Laura Gerrish to make up a ‘quadrille’ team, to dance the Chilpéric Quadrille in the potted version of that show, and a ballet Les Gardes de Cupidon. Sara became a feature of the Soldene shows at the Phil, notably dancing in the hit run of Geneviève de Brabant and performing in the supporting ballet. Soldene reported in her memoirs that it was possible for the risqué cancan to be performed in Islington because the Phil came under the jurisdiction of the Lord Chamberlain not, as the Alhambra did, the Middlesex Magistrates! And so ‘all London’ came to Islington to hear Soldene and see Sara … and Tubby Righton actually did a burlesque imitation of Sarah and her kicking in Gilbert a' Beckett's Christabel at the Court Theatre.

After two years in the safety of the suburbs with Soldene and Morton, Sara (‘the sensation of the past two London seasons’) was headhunted for central London. She was hired to star-dance in

La Belle Hélène at … the Alhambra! When Christmas came the programme was changed to the burlesque

Don Juan and the ballet

Flick and Flock. ‘… in all the ballets of the nations, superior to Russia, Vienna and Rome, comes out the ever popular Mdlle Sara who, if possible, bounds about with a more perfect precision and knowledge of time than ever. Doctors may differ concerning the dancing of Mlle Sara, but her spirits are of inestimable advantage, and her precision is inimitable.’ However, when T

he Demon's Bride was produced once more the cries of ‘indecent dancing’ were raised and Sara pleaded indisposition and dropped out of the show. When she returned for

Le Roi Carotte she and her girls did a ‘modified’ version of their routine.

She was going to America, she was joining Lydia Thompson, she was coining it in Russia …where was she? Well, on 22 May 1875 she was at St Paul’s, Covent Garden, with Lily Wilford and Alhambra comedian Harry Paulton, becoming the wife of ‘long Jack Jarvis’, actor, singer, director, manager, agent and a regular in the Alhambra’s opéras-bouffes.

But in October 1875, she was back on the stage, back with Soldene in a season at the Park Theatre, at the Opera Comique, the Standard, the Surrey, in America, Australia … and Jack left his job at the Alhambra and joined the company for the Down Under trip. The trip was a triumph, but something was awry. Sara was frequently ‘off’, and when the contract was up, and most of the rest of the company extended for more Down Under triumphs, Sara and Jack took the

Whampoa back north. Soon, it was reported, that she had retired from the stage. Aged 23.

Perhaps she should have. Things didn’t go wonderfully henceforth. She appeared for a bit in Philadelphia and in 1881 (14 February) she appeared, billed huge, at Tony Pastor’s ‘Mdlle Sara the original, the wonderful, the great Mdlle Sara, the London sensation dancer …’. After a few nights, she was ‘off’. She appeared in various variety houses, first in America, then in England, she appeared in a tryout of a Harry Paulton play, but when it came to town she wasn’t with it, she did her routine at the Soldene benefit and was hissed, she was arrested and fined 5s for being ‘drunk and riotous’ … and then, 22 July 1887, long Jack died, at the age of 42.

Sara joined up again with Soldene, playing in variety in America, but soon came the news that she was ‘resting in Chicago’. 16 March 1889 she sailed for the last time across the Atlantic and, a few months later, she became Mrs Charles Begbie Slater, wife of a London engineer. They can be seen in the 1901 census at 5 Beaufort Villas, Kingston upon Thames, where Sara died the following year.

A short life, a shorter career, but many years after her triumphs she was still being recalled as ‘the only Sara’.

If Amelia and, especially Sara, had had brilliant but short careers, what to say about Jenny Mills? I first spot her -- ‘a very pleasing operatic and characteristic danseuse’—in 1869. In 1870-1, she was (so she says) with the Colonna Troupe.

And I believe her. Because when she left, she went on the halls with a song ‘Oh, what shall I do when Sarah Wright Leaves?’. Forty years later she is still on the halls …

MILLS, Jenny

No dates, no name, nothing. I’ve looked, my police have looked, and all we have found out is that she was married, or ‘married’ to a comic singer who went by the name of Gus Westbrook. He seemingly told the Brixton electoral officers, between 1898 and 1906, that his name was Augustus Westbrook, I don’t know what he told them the rest of the time. But we’re still trying. Jenny, I suspect, took her well-known name from a popular racehorse.

If the couple are elusive as people, they show up far and wide as performers. I see Gus first at London’s Trevor Music Hall in 1868, I see a Miss Jenny Mills (soprano vocalist) at Maidstone with a Mr Bob Mills (blackface) and at Worcester (13 September 1869) billed as 'danseuse' then at Norwich's Angel Gardens.

I spot the two of them together in May1871 at Wolverhampton and then at Liverpool’s Star Music Hall, Newcastle, Thornton's Varieties ('a triumphant success as serio-comic-dancer'), Hull Varieties et al. At some stage in 1872, they crossed to the Continent, and I spy them at the Wiener Orpheum doing a ‘Medlei duet and English Hornpipe’. Gus does a comic British soldier and Jenny does the Cancan.

I notice they popped back to England for 'a severe domestic afflication' in early 1874. Somebody's mother?

Over the years that follow, I catch up with them at the Walhalla, Berlin, Bischoff’s Odeon in Vienna, the Union, Hannover, 'thirty interior towns in Prussia in 30 days', the Tivoli Copenhagen, in Breslau, Dresden, Warsaw, Stockholm, at the Folies Marseillaises, the Folies Bordelaises, Bordeaux, the Casino in Lyon, the Folies Bergère, Toulouse, the Minden Theatre of Gottenburg … for nine months in Holland .. 945th night in Paris ..

In 1879 and 1880, they are home, appearing at the Holborn, the Sun and Collins’ Music Hall, Jenny 'wore striking and splendid dresses and was very vivacious'; but soon they headed for Europe again. Jenny starred at the Ambassadeurs (

Balaboum XIX) and at the Alcazar d’hiver. In 1884, I see her in Nice and at the Concert Parisien.

Jenny had been cancanning and singing for a dozen years. The Niçois press murmured that there wasn’t that much voice left now, but although Gus had retired from performing in favour of a little management, Jenny had a new trick up her sleeve. How to be a star dancer with limited means. But lots of colour and movement. After some years spent as a single act, all round France, she returned in what seems to have been January of 1893 for her biggest success to date. 'Plus qu'un succès, un triomphe'.

The skirt dance had been made popular, notably by Miss Letty Lind of London, in recent years and a Miss Loie Fuller, sometime understudy to Nellie Farren at the Gaiety, had hit gold by dressing the dance up in a coloured light show. It was a novelty hit, as interpolated into several musicals in New York and London, and in the last part of 1892 ‘La Loie’ got a spot at the Folies-Bergère. And her routine caused a veritable furor in fashionable and esoteric circles. Within weeks, the rival Eldorado came out with its own version of the Danse Serpentine and its limelights, as a part of its annual revue Dans cent ans. And here the ‘dancer’ was Jenny Mills. Some eight years on from her last Parisian successes. And Paris went mad all over again. In the early months of 1893, the two performers played to bulging houses as they searched for new technical and luminescent tricks to dolly up their dances. There was one little not insignificant difference between the two ladies, however. Jenny was a trained dancer of wide experience … ‘L’incomparable Jenny Mills innovera aujourd ‘hui à l’Eldorado deux nouvelles transformations multicolores: qui ajoutera un attrait de plus à la Danse Lumineuse au 20ème siècle’ ... ‘cette incomparable danseuse serpentine’ ‘immense succès’ …

Loie had got in first, if only by a couple of Parisian months, but Jenny had the athletic technique. Some preferred one, some the other. But there was plenty of Paris to keep the tills ringing wildly at the Folies and the Eldorado. And ring they did. 1893 was Jenny’s big year, twenty years after she had cancanned across the Alhambra stage. But it was far from her last. She took her electrical dance show back to Britain -- the ‘Danse Lumineuse’, ‘The Mystique Dream’, ‘her famous Fire Dance’, ‘her Butterfly Dance’, the ‘dance with the spider web’, the water-dance ‘La Cascade’ with 'a display of prismatic colours', the burning of ‘Joan of Arc’ at the stake, 'Les Insectes', 'Les Reptiles', 'Sprites of the Foam', 'the originator of the fire dance', her serpentine and her classical dances, and she appeared over the next two decades in pantomime (1894, Robinson Crusoe at Leeds, Birmingham, Liverpool &c), music-hall, in the theatre in Frivolity with the Leopolds, at the Crystal Palace … to undiminishing enthusiasm. And money (£70 a week in Dundee!).

I see 'la danseuse illuminée' doing her act in pantomime in Bristol in 1899 and at the Empire Theatre of Varieties and Clapham in 1901 and 1904 .. and is that she at Hackney in 1905? Back in France in 1907!

'The world famous fire, serpentine and classical dancer in 1910. And 'Miss Jenny Mills with her company of charming girls in enchanting and bewildering dances' at Folkestone in 1911? I imagine that, forty years and more into her career, Jenny was, like Loie, doing little more than posing in the lighting plot.

Today, it is Loie who gets the credit not only for the electrical dances but, most unfairly, even for Letty Lind’s development of the basic routine. And Jenny, arguably the better dancer and undoubtedly the inventor of some of the ‘luminous’ variations, is well and truly forgotten. But that’s how showbiz‘history’ is made. I wonder how many of the books and articles deifying Miss Fuller even speak of Jenny. Or a Mdlle Diana, whoever she may have been, who was said to have been the best electrically-decorated of them all.

Ah, well, maybe we’ll discover one day who Jenny and Gus were, and what became of them … this is the first stage in the quest …

|

still going ...

|

I should dearly love to know, too, who the other girls in the Colonna troupe were. But these three didn’t put up a bad show for the team. These photographs survive. Sometimes one or the other is labelled as the Colonna troupe. Other times as Mdlle Sara and troupe.

Well, we have photos of Sara and of Amelia … I’m not a physiognomist, but …

And the world has kept on kicking ....

Truthfully, I liked the cancan better as what it started out as: a simple, crazy quadrille for four mad dancers ...

|

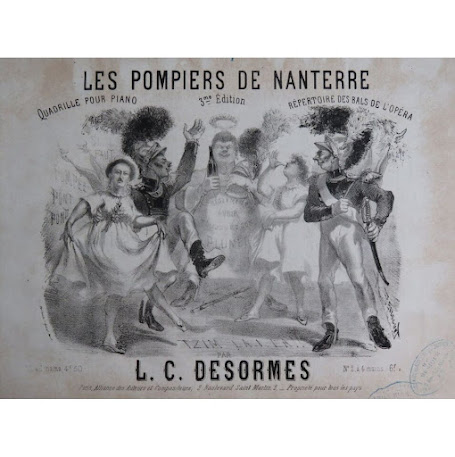

| 1868. The cancan (?) gone posh |