.

It’s the two-hundredth birthday of composer Jacques Offenbach this week, and, all round the globe, lovers of his wonderfully sparkling music have been marking the occasion with productions of his stage works, large and small. The event has also provided those whose world is the written page, rather than the performing stage, with the opportunity to wade into print with lucubrations, equally large and small. I’ve seen only a few of these, and I think that the stage productions (which, alas, have not reached New Zealand) have probably got it all over them. Well, they ought to have. You can listen to Ba-ta-clan or Orphée aux enfers or their confrères a hundred times, and never tire of them. But after the first really well-researched and knowledgeable books and articles on the musician and his works had been published, well, what more was there to say and write? As a result, the same material has, largely, been repeated or copied, over and over again. Errors sometimes included! Of course, this is the twenty-first century, where footnotes are considered more important that facts; the heyday of ‘theorising’ rather than fact-finding … but I’m ‘of an earlier age’, I like my first-hand facts, so, when the theses are flying, I keep my head down. And, thus, I haven’t clambered on to the Offenbach bandwagon of 2019. What could I say, that Jean-Claude Yon, for example, couldn’t say better?

My contribution to the bicentenary took the form of sponsoring a grave marker, in the wilds of Sydney, Australia, for the unmarked tomb of Johnny Wallace, one of the most important of nineteenth-century British directors and players of opéra-bouffe. But these things have a way of catching up with you. I got asked for the use of some of my research work on the great performers of the Offenbachiade, which led to my penning a wee piece on its unduly neglected star lady, Lise Tautin, who, in the popular memory, has languished far too long in the shadow cast by her colourful successor, Hortense Schneider. Which led me to further diggings into the personnel of the earliest days of Mons Offenbach’s career as a producer, at the Bouffes-Parisiens.

There is nothing much left to say about the great comic players of the first years of the Bouffes company ... Desiré, Berthelier, Léonce, Pradeau … but the surprising thing is the comparative lack of interest that has been shown in the much smaller, but equally important, group of ladies of the troupe. So I thought I’d devote a few lines to them, the feminine creators of the early opérettes (1855-1860) of the Bouffes-Parisiens.

Here are the ‘cast members’ in order of appearance:

Hortense [Catherine] Schneider (b Bordeaux 30 April 1833; d Paris 5 May 1920)

Marie [Denise Victoire] Dalmont (b Paris 10 July 1831; d Brussels 1 December 1878)

Mlle Nevers

[Adèle] Claire Courtois (b Saint-Quentin 12 September 1831)

Emma Hesme[z]

[Marie] Aurélie Mareschal (b Paris 29 December 1837; d Marseille January 1862)

Marie Garnier

Juliette Desirée Byard (b Paris 16 November 1839; d Passy 3 March 1866)

Louise Abigdon [Louise Charlotte Abigdon Legaigneur]

[Marie Emilie] Coraly Geoffroy [Caroline Marie Emilie Guffroy] (b Paris 8ème 15 August 1841)

Lise Tautin [Louise Emilie Victorine Vaissière] (b Yvetot, 31 January 1834; d Bologna, 12 May 1874).

[Marie] Pierrette [Amélie] Chabert (b Paris 7 November 1833; d Paris 3 December 1916)

Marie Cico [Alexandrine Louise Hortense Trotté] (b Paris 4 July 1841; d 4 Passage Masséna, Neuilly 9 September 1875)

Victoire Zélie Felicité Engalbert (Mme Penot, b Paris 2 November 1836)

Lucille [Emilie] Tostée (b Paris 19 December 1837; d Pau May 1875)

|

| Lina Kunzé |

The original little team at the Bouffes (5 July 1855) featured only one vocalist/actress, as well as three danseuses who performed with Mons Derudder in the pantomimes, a type of item which was abandoned in the second year. The numbers of feminine performers would, however, grow, as the legal restrictions on the size and nature of the pieces played gradually permitted: 4 March 1856, Le Thé de Polichinelle featured no less than thee ladies in its tiny cast, by the time of Six Demoiselles à marier (12 November 1856), some extra demoiselles had to be called in, alongside the regulars, to make up the titular number, and 19 November 1857 saw the production of the innovative Les Petits Prodiges with its cast of twelve, featuring almost all the regular ladies of the troupe. And less than year later, it was time for Orphée aux enfers, with its innumerable cast of gods and goddesses, as the original Bouffes programmation headed towards a very different shape and style of production, where full-length pieces took over from the original spectacles- coupés.

So, who were the girls who created this vast opus of short opérettes, some bouffe, some rural, some occasional, none serious, a splendid number of which have remained, to this day, in the playable repertoire? Well, here goes.

Marguerite Macé. Of all the girls of the early Bouffes troupe, Mlle Macé, or Madame Macé-Montrouge as she became after her marriage to actor Louis Hesnard dit Montrouge, had easily the longest career as an actress at the top level. If she did not have the blazing moments in the starlight that several of her colleagues did, she was still creating important roles in the musical theatre forty years on from her debut. That debut seemingly took place at the Gymnase in 1850. Mlle Macé’s early life seems to have been rather irregular. ‘She was brought up by her grandmother in Batignolles … went to the Conservatoire aged 10 …’. Well, whenever she was born, and under what conditions, we catch up with her in April 1850 (surely not aged 13!) playing Francinette in La Volière at the Gymnase. Ill with nerves, she forgot her lines … but, by her second role, Laure in Les Pupilles de Dame Charlotte she was praised: ‘impossible d’avoir plus d’esprit, de gentillesse et de vivacité’. ‘A beginner aged 16 …’. Yes, well that is the ‘born 1836’ bit blown apart! And ‘pupil of Nicolo Martyns’ don’t sound much like the Conservatoire. In 1853, she moved to the Vaudeville, in 1854, I spot her at the Théâtre de Montmartre, and then she is engaged by Mons Offenbach …

|

| Marguerite Macé-Montrouge |

|

| husband Louis Montrouge |

She played in the prologue and the three-handed Une nuit blanche on opening night, and went on to create more than a dozen further pieces at the Bouffes: Une rêve d’une nuit d’été, Une pleine eau, Le Violoneux, Le Duel de Benjamin, Elodie, Le Thé de Polichinelle, Les Pantins de Violette, and, after some months off, Six Demoiselles à marier, Après l’orage, Dr Miracle (x2), Le Roi boit, Rompons!, Les Petits Prodiges, Mamzelle Jeanne, La Charmeuse, La Chatte metamorphose en femme. She also played in other repertoire pieces such as Tromb-al-ca-zar, La Bonne d’enfant in Paris and on tour, notably in a visit to London. Her three years at the Bouffes climaxed when she took over the role of L’Opinion Publique in Orphée aux enfers during rehearsals, as it turned from a male role to a female one.

Her time done at the Bouffes, Mlle Macé moved on to start what would be the body of her career, much of it in tandem with her husband or under his management, and all of which has been written up in mostly correct detail (give or take those iffy origins) in many a French magazine. In 1886, avowedly 50, she created the classic musical comedy mother as Madame Jacob in the hilarious Joséphine vendue par ses soeurs, in 1890 another komische Alte as the Senora in Miss Helyett …

If you can only have one woman in your theatre troupe, you need a quadruple threat, and Mlle Macé seems to have been an excellent choice!

However, Mons Offenbach, manager had expansive ideas, and before the year was out he had hired three more ladies, of vastly different backgrounds, and vastly different futures, to play at his theatre.

The first to appear was Miss Hortense Schneider, girlfriend of his star comedian Berthelier. I’m not going to get into the Schneider tales, of which there are many and varied. I will just say that she made a charming effect when she played Mlle Macé’s roles in Une pleine eau, Le Violoneux, Elodie and Les Pantins de Violette and created parts in Le Thé de Polichinelle and, most effectively, in Tromb-al-ca-zar, a role which was later taken by Macé, and La Rose de Saint-Flour. Mlle Schneider’s time would come later. For now, she was an accessory to Marguerite, and to the new star signing of the Bouffes troupe.

|

| Hortense Schneider |

Marie Dalmont, daughter of a respected Parisian musician and teacher, now based in Metz, had benefitted from a sound musical education. I note her singing Haydn in concert, ‘aged 14’, in Metz in 1847, before she headed for Paris, the Conservatoire, and, in 1855, first prizes for both singing and opéra-comique. Mons Offenbach beat the Salle Favart in the action for her services (‘au poids de l’or’) and composed the little (Paimpol et) Perinette for her debut (5 November). She did not disappoint. She was voted totally delicious, and it seems from contemporary reports that she was, of all our ten ladies, perhaps the most uncomplicatedly successful as a vocalist.

The following month, she created the role of Fe-an-nich-ton in Ba-ta-clan to delighted reviews and great success, then followed up, over the three years that followed, in Le Postillon en gage, Le Thé de Polichenelle, as the prima donna, Sylvia, in the Offenbachian rearrangement of L’Impresario, as Violette to the Pierrot of Schneider in Les Pantins de Violette, Fleur de Lys in the shortlived Le Guetteur de nuit, Le Financier et le Savetier, M’sieu Landry, Les Trois baisers du diable, succeeded to the lead roles in Le Rose de Saint Flour, Croquefer and Le Violoneux, created L’Opéra aux fenêtres, Le Troisième Larron, Le Mariage aux lanternes, Bruschino, the flop Maître Baton …and then things changed. When Orphée aux enfers was produced, Lise Tautin was cast in the prima donna role. Marie Dalmont performed M'sieu Landry (as Madame Parfait) and de Rillé’s Frasquita as the forepiece.

|

| Marie Dalmont in Le Financier et le savetier |

But more than that had changed. Some months earlier, Marie had married the Belgian baritone Pierre-Joseph de Mesmaecker, and, in 1859, she quit the Bouffes and headed, the following year, to New Orleans as leading lady of a French opera troupe. She played Isabelle in Robert le diable, Berthe in Le Prophète, Catarina in Les Diamants de la Couronne, Henrietta in Martha, Marie in La Fille du regiment, Leonora in Il Trovatore … to a grand reception, then headed home to sing more of the same in Marseille, alongside the splendid Mme Montenegro, and then around the world. Now ‘Mme de Mesmaecker’, I see her doing seasons in Montpelier (1862-3), Lyon (1863), Toulouse and Angers (1864) and Antwerp (Faust, Ernani, Rigoletto, Roland à Roncevaux), before she and her husband joined impresario Emile Lemoigne for a long engagement in Batavia. On their return, she appeared at Rouen (1867), the Brussels Cirque (1868), Montbéliard, before taking a full about-turn, and renouncing opera to return to Paris to appear in a series of one-act opérettes. Between 1871-3, I spot her at the Tivoli (Le coq de Boétie, Les Turcos en Indocochinchine), the Folies-Bergère (Les Oreilles d’âne) and the Folies-Marigny (Le coq de Béotie, Quand nous serons à dix), before she disappears from view. She died a few years later, before her husband had reached the outstanding peak of his career, and before the long career of their son, Georges, at the Opéra-Comique.

|

| Joseph Mesmaecker in La Fille du Tambour-Major |

Whether ‘Mlle Nevers’, whoever she may have been, was another managerial punt, as Schneider had been, I cannot tell. Maybe she was only ever intended to be a back-up/takeover/small part player. That was all she achieved. The comédie aux ariettes, Dans un volcan, programmed for the theatre’s re-opening, with another new piece, and announced for her debut, seems to have only been played once, while the other piece on the bill, Ba-ta-clan, triumphed. She took a small part in the occasional piece, Les Dragées de la baptême, played some performances of Elodie and Le Postillon en gage, and went her way, leaving no trace.

As for Mlle Hesmez or Hesme, sometime chanteuse légère at the Lyon Grand Théâtre (1854, Les Diamants de la couronne, La Dame blanche), she seems to have arrived a few months later, from Metz (do I see the hand of Papa Dalmont?). She was given every chance. Puffed in the press, she made her first appearance in the proven Pépito, then as Venus in Vénus au moulin d’Ampiphiros, after which she was given roles in Les Dragées de la baptême (behind Maréschal) and Le Guetteur de nuit (behind Dalmont). Three less-or-more flops. So Pépito was brought out again. The pretty girl, of whom the Figaro had praised the 'charme, intellingence et distinction', with the little voice, then disappeared from theatrical annals.

The nearest thing to success during this intake period was Claire Courtois. Like Marie Dalmont, she had been a pupil at Conservatoire, from where she had graduated with a second accessit. She began at the Bouffes in February 1865, playing Simonette in En Venant de Pontoise, before being allotted the second soprano role, behind Dalmont, in L’Impresario. She subsequently created Un Duo de Serpents, succeeded Macé and Schneider as the heroine of Le Violoneux, introduced the role of Marinette in Marinette et Gros-René and that of Eléanore in L’Orgue de Barbarie. She proved well-enough liked but she was going nowhere. She ultimately became a member of the Paris Opéra chorus.

Another to-be-core member of the troupe had, already, made her arrival at the theatre. Aurélie Mareschal (sic) was another secondary Conservatoire prize-winner from the crop of ’55, but she proved to have the right temperament for the Bouffes, and went on to make a splendid mini-career with Offenbach. Given her chance in the brief Dragées de la baptême and confirmed when taking over the part of Pierrot in Les Pantins de Violette, she was given the creation of the part of Grittly in Le 66. Its success led to her being allotted the premieres of Hassenhut’s Le Cuvier, then as Suzanne in M’sieu Landry with Dalmont, before she introduced another memorable role as Fleur-de-Soufre in Croquefer. The British press, writing of the new little theatre quoth ‘Dalmont and Mareschal are the favourite lady artists’. Britain was soon to find out: the pair led the Bouffes company to London, for a season at the St James’s Theatre, where Aurélie played Croquefer, Pépito, Le 66, Le Savetier et le Financier, Les Pantins de Violette, L’Orgue de Barbarie to delighted audiences through two summer months. Back in Paris, she joined Dalmont and new-girl Lise Tautin to create Mariage aux lanternes, featured in Les Petits Prodiges and the Haitian opérette Simonne, played Vent du soir, and introduced Delibes’s L’Omelette à la Follembuche. She had no role in Orphée aux enfers, and, when the piece ran on and on, the authors decided to write in the part of Amphitrite for her. They did not make the same error twice: in 1859, when Geneviève de Brabant was launched it was Aurélie who was Geneviève. When she moved on, it was to the Théatre Déjazet (Cicalda in Double deux), and soon after to Marseille … where, so the Conservatoire records say, baldly, that she died in January 1862. And no one seems to have noticed.

|

| Aurélie Mareschal |

|

| Aurélie Mareschal |

|

| Marie Garnier |

Next up, came Marie Garnier. Petite, fashionably plump and pretty Mlle Garnier’s name has survived as having been ‘the Vénus of Orphée aux enfers’, ‘l’étoile rousse’, which I can only imagine means she did nothing more memorable than that, were it not that she was, in 1866, one of Alexandre Dumas’s long lines of conquests. ‘Three nights in Hyères’ someone commented. However, the lass obviously could act and sing a bit, for she had begun her career singing at the Théâtre Lyrique, in Si j'étais roi, and such roles as Gertrude in Le Maître de Chappelle, Marie in Mam’zelle Geneviève, Jeanne in Le Chapeau du roi, Marguerite in Le Roi d’Yvetot, Marotte in Le Bijou perdue, Brigitte in Le Colin-Maillard, Héya in Jaguarita l’Indienne, Donna Carmen in Le Muletier de Tolède, Mina in Le Habit de Noce, Jeanne in Le Chapeau du roi et al, between 1852 and 1856. She then moved to the Bouffes, where she made her first appearance in a new Offenbach opérette La bonne d’enfant.‘Jolie blondinette, à la mine éveillée; elle chante avec gout et sa voix a du charme’ nodded the press, as Mlle Garnier went on to play in Six demoiselles à marier (with castanets), Après l’orage, Atala in Vent du soir, Estelle in Les petits prodiges, and created the Vénus of Orphée. And then …? Did she just stop? Did she prefer the life of a demi-mondaine to that of a singer? Ah, no! There she is (1863) at the Théâtre des Jeunes-Artistes, and in 1867, touring in Italy with 'the troupe of M Herman' in 'all the Schneider roles'. Surely she is not the same Marie Garnier who turns up at Havre in 1872, as a singing teacher in 1880s Paris …? Was her name, even, really Marie Garnier? Oh, well, this time we have a picture -- loads of pictures, for she was much photographed -- but not a lot of facts.

Next up, came Marie Garnier. Petite, fashionably plump and pretty Mlle Garnier’s name has survived as having been ‘the Vénus of Orphée aux enfers’, ‘l’étoile rousse’, which I can only imagine means she did nothing more memorable than that, were it not that she was, in 1866, one of Alexandre Dumas’s long lines of conquests. ‘Three nights in Hyères’ someone commented. However, the lass obviously could act and sing a bit, for she had begun her career singing at the Théâtre Lyrique, in Si j'étais roi, and such roles as Gertrude in Le Maître de Chappelle, Marie in Mam’zelle Geneviève, Jeanne in Le Chapeau du roi, Marguerite in Le Roi d’Yvetot, Marotte in Le Bijou perdue, Brigitte in Le Colin-Maillard, Héya in Jaguarita l’Indienne, Donna Carmen in Le Muletier de Tolède, Mina in Le Habit de Noce, Jeanne in Le Chapeau du roi et al, between 1852 and 1856. She then moved to the Bouffes, where she made her first appearance in a new Offenbach opérette La bonne d’enfant.‘Jolie blondinette, à la mine éveillée; elle chante avec gout et sa voix a du charme’ nodded the press, as Mlle Garnier went on to play in Six demoiselles à marier (with castanets), Après l’orage, Atala in Vent du soir, Estelle in Les petits prodiges, and created the Vénus of Orphée. And then …? Did she just stop? Did she prefer the life of a demi-mondaine to that of a singer? Ah, no! There she is (1863) at the Théâtre des Jeunes-Artistes, and in 1867, touring in Italy with 'the troupe of M Herman' in 'all the Schneider roles'. Surely she is not the same Marie Garnier who turns up at Havre in 1872, as a singing teacher in 1880s Paris …? Was her name, even, really Marie Garnier? Oh, well, this time we have a picture -- loads of pictures, for she was much photographed -- but not a lot of facts.The prize-winning Juliette Byard (Mme Chollet) was, for some reason, a failure. After some appearances at the Theâtre de Montmartre and at Batignolles, she played at the Bouffes in L'Opéra aux fenêtres, in Six Demoiselles and took over in L’Orgue de Barbarie, but seems to have been ‘of the reserve’ only. She was tried at the Opéra-Comique after her Bouffes time (Le Toréador, Pascal’s Cabaret des Amours, L'Illustre Gaspard), but died while still in her twenties, in 1862.

|

| Abigdon |

Mlle Abigdon (otherwise Louise Charlotte Abigdon Legaigneur), daughter of a provincial performer was tried in parts in Les Trois baisers du diable ('jolie débutante qui promet une excellente petite actrice') and Le roi boit. No one complained, but she was soon gone. It seems she went to houses where her physique and acting were appreciated.

|

| Louise Abigdon |

But firepower was lurking. The company, with Marie Dalmont and Aurélie Mareschal at its head, quit Paris for London. And, in their absence, new girls stepped in to take their places. The ‘new Dalmont’ would be Lise Tautin, the ‘new Mareschal’, a little lass named Coraly Guffroy (sic), who was admitting to fifteen years of age.

I have told the tale of Lise Tautin, who would become the Queen of the Bouffes, and epitomise the 1850s world of opéra-bouffe, already, but Coraly … just a word or ten on Coraly, because Coraly, too, would become a star.

|

| Coralie Geoffroy |

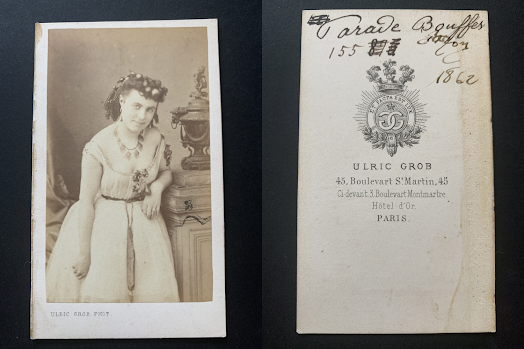

'Coraly' Guffoy, later Mme Geoffroy. Yes, wife of the actor Auguste Charles Julien Geoffroy of the Bouffes and a lot of other places, married in Berlin (20 October 1858). Anyway, whencever she came, she can be seen at the Salle de la Fraternité in 1851, ‘aged 7’ giving ‘Le Petit Chaperon Rouge’ and ‘La Lisette de Béranger’, at the Jardin Paganini, the Chapelle St-Denis … The internet throws up a letter written by the lass in 1853 ‘aged 11’. And there she is at the Bordeaux Variétés, ‘la petite Coraly Guffroy’, playing multiples roles in Le Vieux garçon and starring in L’Orpheline du Château with songs ‘Le Fils à Jerome’, ‘Une caprice de Jeanneton’, ‘La Légende du grand étang’. And here she is in Metz and Valence, in 1855: ‘cette charmante enfant qui chant comme une première chanteuse’. And in Belgium, 1856, ‘cantatrice de 14 ans’. So, maybe.

Anyway, she came to the Bouffes in 1857, and made her debut there in a pretty little novelty entitled Dragonette which proved a decidedly charming, if not very ‘bouffe’, addition to the programme, following up in Pauline Thys’s La Pomme de Turquie. When the main company proved a hit in its London season, Coraly was called over to give her two little pieces. Back in Paris, she played in La Momie de Rosoco, Au Clair de la lune, Les Petits prodiges, La Charmeuse and joined the company’s next trip, to Krolls Theater, Berlin, joining Mlles Chabert and Tautin in the company’s repertoire and getting wed. When Orphée was produced, she was cast as Cupid, when Le Roi boit was revived, she played it... She joined Tautin in introducing the successful Un Mari à la porte before she moved on. She moved in 1859 to the Opéra-Comique (Fauconnier’s La Pagode, Rendez-vous bourgeois, Don Gregorio, Jeannette in Le Deserteur, Le Roman d’Elvire) and then to the Châtelet and the Cirque, where she starred as Fanfreluche in La Poule aux oeufs d’or, the Princess Miranda in Rothomago and Claudine in La Prise de Pekin. But she then abandoned the spectaculars and headed for Strasbourg, followed by a visit to Baden-Baden for the season. There, while Geoffroy appeared as Juliano in Le Postillon, she triumphed as Zerbine in La serva padrona and created the part of Ursule in Berlioz’s Béatrice et Bénédict (9 August 1862) and the Priestess of Apollo in Reyer's Erostrate. They also appeared together (he, mute!) in Schwab’s Les Amours de Sylvio and Le Domino noir.

The ‘adult’ part of Coraly’s career, which stretched over some three decades, took her far and wide. I see her in Bruges (1863, Tromb-al-ca-zar 'succès fou'), Ghent (1864-5, La Chatte merveilleuse, Mireille), Marseille (Le Châlet) on tour with tenor de Quercy (1866), at Lyon with Berthelier (1868, La Belle Hélène) and is that she singing Mignon and Robinson Crusoë in Geneva (1868)? Or playing La Grande-Duchesse and La Rose de Saint-Flour at Algiers? In 1869-70, she is at Lille (Petit Faust, Le Châlet, Tutti in maschera, La Belle Hélène) and Bruges (La Grande-Duchesse), in 1871, she sang Barbe-Bleue at Brussels, and in 1872 created the role of Heloise in Litolff’s Héloise et Abélard in Paris. 1873 sees her at St Petersburg, 1874 at Cairo, 1875 sees her leading Carlo Chizzola’s opéra-bouffe company in America, 1876-7 she is at the Folies-Dramatiques, reaping superb reviews for her Marguerite in Le Petit Faust, and creating La Foire St-Laurent (Malaga), in 1878 she replaced Peschard as Eurydice in a revival of Orphée aux enfers, and was first lady at Nantes. 1880 it was Brussels, 1882 Athens, 1882-3 Boulogne …

I’m sure she went on, she was after all, only fortyish. But I lose her. And her husband (who must not be confused with the well-known comedian of the Gymnase). But little, plump, exuberant Coraly had already accomplished a huge career.

Although these last two excellent artists had come from the theatre of experience, Offenbach – in hope, I imagine, of another Dalmont -- still culled new singers from the Conservatoire prize-lists. Dalmont had been the top winner in 1855, in 1857 it was Pierrette Chabert. I wonder if he had tried for the 1856 laureate. She was by name Céline de la Pommeraye, and the Opéra got her. Later, she became ‘Rose Bell’ and an international star of the opéra-bouffe. However, Mlle Chabert (whom the Internet and the BNF insist on calling ‘Marguerite’ .. that was Chapuy) was definitely an acquisition.

After her studies, and a successful appearance in the Paris concerts, she joined the company at the dawn of 1858, and played in Mam’zelle Jeanne, the little heroine, Ciboulette, of Mesdames de la Halle and Corilla in Bruschino, before voyaging with the troupe to Berlin for the summer. When Orphée aux enfers was cast, later that year, she was given the featured role of Diana. She introduced L’Île d’amour, Le Fauteuil de mon oncle, Le Polka des sabots, the role of Eglantine in Geneviève de Brabant, Hignard’s Nouveau Pourcegnac, played in Le Carnaval des revues, teamed with Marie Cico as the two naughty nymphs of Daphnis et Chloë, created Le Sou de Lise, the central role of Laurette in La Chanson de Fortunio, played Atala in a revived Vent du soir and the title-role of La Servante à Nicolas. And then, in 1861, she moved on. But she moved on and up. Over the next decade she would become recognised as one of the best provincial ‘dugazon’s in France, as she travelled with her repertoire of operas-comiques and opérettes from one city to another (and usually back again), hired over and over, and ever successful.

Le Havre and Versailles seem to have been her first engagements. In 1863, I see her singing Siebel in Faust and Nancy in Martha at the former and La Dame blanche, Les Mousquétaires de la reine, Les Diamants de la couronne, Le Caid, Pré-aux-clercs, Fra Diavolo, Les Noces de Jeannette and even Adalgisa in Norma at the latter. She returned regularly to Versailles right up to 1870. She visited Troyes (Le Songe d’une nuit d’été), before being hired as dugazon at Angers, where she won vast applause for her Eurydice, then Boulogne, before making a trip to sing French opéra-comique at Barcelona (‘très gracieuse et chante très bien’) with a certain M Vincent. Returning to France, the pair took an engagement at Nancy, where Mlle Chabert appeared in all sorts, from La Veuve Grapin and Les Pantins de Violette of the Bouffes repertoire, to Georgette in Les Dragons de Villars to Inès in L’Africaine. Poitiers, a long stint back at Versailles, where amongst others, she played Haydée, Adalgisa, Pippo in Gazza Ladra, and the role that would become her ‘best’: Ambroise Thomas’s Mignon whom, the press acclaimed, she transformed from a whingeing creature into an interesting character. She made a return to Le Havre, I see her at Brest (1870), Amiens (Barbe-bleue, Le Petit Faust, Mariage aux lanternes, Mignon, Les Cent vierges, Le Docteur Crispin), Caen, and at Toulon (1873-4) where she made a triumph as Lange in La Fille de Madame Angot (‘Mlle Chabert chante et dit à la perfection le role de Mlle Lange’) and played the saucy Müller in La timbale d’argent as well as Jemmy in Guillaume Tell and Flora in La Traviata … in support of the company’s contralto!

And then, to all appearances, she stopped. Marriage? Death? Neither were reported. A ‘Mlle Chabert’ turns up in the Variétés revue in 1881 … so, alas, once more, no personal story to go with the professional one. And no button. Bother.

Although Mlle Chabert’s departure from the Bouffes was mourned by press and public, Offenbach’s theatre already had two new girls in its lists who were to make altogether more of splash in the world than she.

Lucille Tostée was one. And I can really only reprint here a version of my piece on her from my Encyclopaedia of the Musical Theatre.

|

| Lucile Tostée |

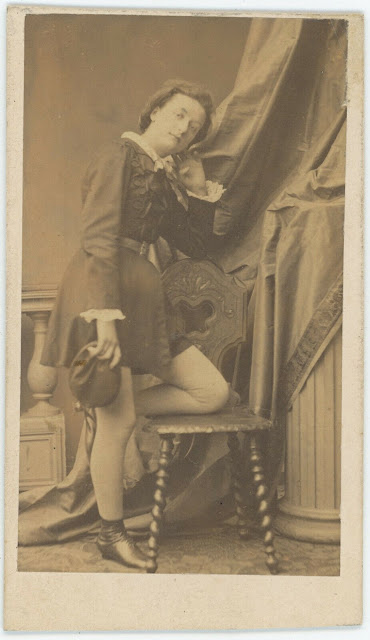

‘Although Lucile Tostée was to make the most famous part of her career in America, she began her life on the stage in France, becoming one of Offenbach's principal interpreters at the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens at a young age. Amongst her assignments at the Bouffes, she played Scipionne in Les Vivandières de la grande armée, the title-role in Flotow’s La Veuve Grapin (1859), Le Polka des Sabots, Forteboule, Le Nouveau Pourcegnac, Delibes’ Belle Étoile, Croquignole XXXVI, Le Carnaval des Revues, Hermine in Le Petit Cousin, Zerbinetta in Titus et Bérénice, L’Étoile in Le Roman comique (1861) and the original version of the page, Amoroso, in his Le Pont des soupirs (1861). She donned skirts to play Béatrix in the Parisian version of Les Bavards (1863) but went back into travesty in the rôle of Fabricio in Il Signor Fagotto (1864). She also appeared with the Bouffes company at Vienna's Theater am Franz-Josefs-Kai in 1861 (Croute-au-pot in Mesdames de la Halle, Fanchette in Une nuit blanche, Pierrette in La Rose de Saint-Flour, Atala in Vent du soir) and in 1862 (Dorothée in La Bonne d'enfants etc). Following the advent of Zulma Bouffar into his life and theatre, Tostée apparently found less favour in Offenbach's eyes, but her career did not by any means go downwards as a result.

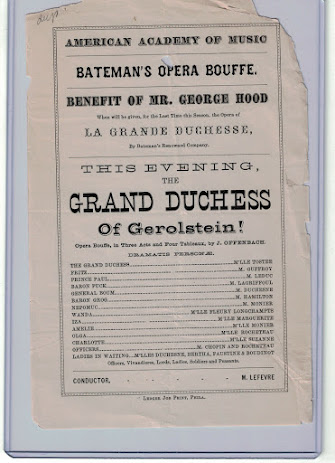

In 1867 Lucile Tostée headed a troupe exported from Paris under the management of H L Bateman to play French opéra-bouffe at New York's Théâtre Français.

On 24 September she opened in America as Offenbach's Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein and she took the town by storm, launching at the same time the craze for opéra-bouffe which was to sweep the country over the following years. One critic rhapsodised “The new opéra-bouffe’s a brilliant success, the music most sparkling, allow us to state, man, and while they’ve Miss Tostée to play ‘La Duchesse’, there’s no grounds for fearing the crowds will a-Bate-man’.

She appeared throughout the United States in that season and the next in a variety of such pieces including La Belle Hélène, Lischen et Fritzchen, as Eurydice in Orphée aux enfers, and in her original rôle from Les Bavards, sharing the top billing in later days with Mlle Irma [Marié], who had been starring in an opposition production of Barbe-bleue and who amalgamated her forces with Bateman's in order to reinforce a company which was, by that time, being challenged for opéra-bouffe supremacy by an oustanding team brought out by Jacob Grau and headed by Rose Bell, Marie Desclauzas and Gabel.

Equipped with some fairly dubious advertising -- Tostée's Eurydice was described as `her original rôle played by her 300 nights in Paris' -- the pair continued, increasing their repertoire with such pieces as Monsieur Choufleuri (with Tostée in the vocally demanding rôle of Ernestine), Le Mariage aux lanternes, La Chanson de Fortunio (Valentin) and Maillart's Les Dragons de Villars. When Tostée left America after less than two years, the flood that she and La Grande-Duchesse had begun continued in the hands of such other French artists as Irma, Marie Aimée, Léa Silly, Céline Montaland, Marie Desclauzas, Coralie Geoffroy, Louise Théo and Paola-Marié, as well as their English-language followers. And Tostée herself? She went home, and, there, apparently, just vanished from theatrical annals. And after 1875 from all annals'.

Another vanishing one. But our last lady did not vanish. Not in that way. Marie Cico, like her successful older sister (?), Pauline, is said to have chosen the high life, the diamonds and the demi-monde as a pendant to her life on the stage. And, like Blanche d’Antigny, and countless others, she died of it, at a young age. Which was, decidedly, a waste. For Mlle Trotté, who chose, for reasons unknown, the unattractive name ‘Cico’ for the stage, was a fine performer. Well, Lyonnet says ‘beware of mixing up the two Mlles Cico’ and then, promptly, does just that. So do many others. I have tried to unmix them. The Mlle Cico at the Théâtre Montansier and the Jardin d’Hiver in 1851, and thereafter displaying her charms most liberally at Le Havre and the Vaudeville, at the start of a career as a beauty and actress (and sometimes dancer and singer too) at the Palais- Royal is Pauline.

|

| Pauline ... covered up! |

Marie, apparently with a stage mother behind her, was singing duets at the Casino du Marché au Poulet in Brussels, with a certain Zulma Boufflar, at the age of eleven, and dancing in a Parisian café-concert soon after. She came to the Bouffes in 1858, where she was cast as one of the ‘marchandes’, behind Tautin and Chabert, in Mesdames de la Halle. Later raconteurs would say that she had been a ‘coryphée’ at the Bouffes, but that is wrong. Her second role was with Tautin and Dalmont in a reprise of Mariage aux lanternes, when M’sieu Landry was staged she was Suzanne to the Madame Parfait of Dalmont, she was Minerva in Orphée aux enfers, took her turn at Le Violoneux, created leading roles in Le Major Schlagmann, Forteboule, Belle Étoile, Croquignole XXXVI, Le Carnaval des Revues and C’était moi, and the dual role of La Hire/Clé de sol in Geneviève de Brabant. At the same time, she entered the Conservatoire where she studied under Révial and Mocker, and began singing in regular concerts

In August 1861, having left the Bouffes, she graduated with the premier prix, and she was subsequently engaged for the Opéra-Comique. She would remain there for a decade – beginning in Le Domino noir, Les Mousquetaires de la reine, La Dame Blanche, -- ‘rayonnante de beauté et de talent’ – creating the title-role in David’s Lalla Roukh and Hermine in his Saphir, Figarina in La Fiancée du roi de Garbe, Berthe in Le Voyage en Chine, Sylvie in Gounod’s La Colombe, Madame de Grandval’s little La Pénitante, Edwige in Offenbach’s Robinson Crusoe, Mimi in his Vert-Vert, and succeeding Marie Cabel as Philine to the Mignon of Galli-Marié and as Hélène in Le Premier Jour de Bonheur, amid repeated items of the established repertoire. In 1872, she was not re-engaged at the Salle Favart, and – with her health showing signs of deterioration – she returned to opéra-bouffe, as Eurydice in the Gaîté revival of Orphée. But her final illness was upon her, and, at age 34, she died. She left a ‘fatherless’ son, many regrets … and a mystery or two.

|

| Marie Cico |

So, there they are, the ladies of the original Bouffes troupe. The singing ladies, that is. For the original dancing ladies – Clara and Rosa Price, and Mlle Mariquita – were also well- chosen. The Price girls hailed from Denmark, and were members of the large dancing and acrobatic dynasty fathered by a British pantomimist who had made name and fame there, and whose family troupes had toured Europe with notable success. As for Mlle Mariquita (born in Algiers, date and surname unconfirmed, but it seems to have been 'Mariquet'; d 1922), she was to have a long and prominent career as a star dancer, at the Porte Saint-Martin, the Folies-Bergère and the Opéra, at Madrid, Barcelona and with Espinosa at London’s Princess’s Theatre, and later as one of Paris’s favourite choreographers in opera, opéra-comique, opérette and spectaculars, of which the Opéra-Comique ballet of ‘baigneuses devêtues’ in Le Mariage de Télémaque was a favourite. She has been the subject of a number of learned dissertations, so I need to dissert no more.

|

| Mariquita allegedly aged 8 |

Now, I really must get back to translating Petrus Borel. These ladies took me down all sorts of interesting side paths ...

I wandered back this way, a year later, in search of one 'Ida Klose' 'of the Bouffes-Parisiens'. A couple of years later than these ladies, but ... it wasn't a very successful 'wander' ...

All I can find about her is that she was from Berlin, and played a Gastspiel at the Bouffes in 1862. Actress? Dancer? I know not. Anyway, she had her photo taken and I discover her name in a photographer's catalogue with a whole heap of other also labelled as 'of the Bouffes'. Some are old friends: Tostée, Pfotzer, Tautin, Maréschal, Garnier, Lina Kunzé .. then there are Rose Deschamps, Mlle Desvignes, Mlle ?Luci[l]e, Henriette Vernon, Louise Leclère, Mlle Jeanne, Mlle Fournier, Mlle Nattier ...

'La delicieuse petite blonde' Rose Deschamps (née Céleste Rose Beauregard), I know. Small part player at the Variétés (1858, Marie in Deux merles blancs) then at the Bouffes. Seen in Geneviève de Brabant (Blondette), La Chanson de Fortunio (Guillaume), as the third Venus in Orphée aux enfers ... Nicette in La Charmeuse (1860) .. who, in 1862, left to join the troupe at the Comédie Française! One story says she auditioned. Another says she was 'imposed' on the management by the Duc de Morny. The engagement caused a small 'scandale', but she proved perfectly adequate, and stayed until she was 'retired' in 1869. Lyonnet records that she was still active on the Paris stage in 1884.

|

| Lise Tautin and Rose Deschamps |

Mlle Deschamps (b 1845) was, so an old theatre-goer related, 'une des femmes les plus appetisantes et les plus recherchées de sa génération' (Le demi-monde sous le second empire). Here she is with the theatre's star, Lise Tautin.

Well, here is Mlle Desvignes. I've no idea what she did at the Bouffes but ... ah, yes! there she is in 1860 cadt as Eriphyle in Daphnis et Chloe with Mlles Juliette Beau, Chabert, Cico, Tafanel (sic), Lasserre, Lecuyer, Grandet, Ida ...

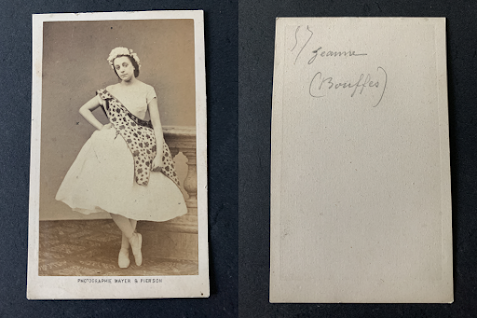

And here is Mlle Jeanne. She was second page in Geneviève de Brabant. A thinking role. The girls who had just a prenom, with no surname, were usually decorative extras and walk-ons. Playing pages gave them an excuse to show their legs ...

She doesn't seem to be the same Mdlle Jeanne who was a decorative item in Grisar's Les Amours du diable a bit earlier ..

Then there are Mlles Louisa, Gabrielle Rose, Aimée (no, not THE Aimée), Charlotte, Augusta ...

Getting back to principal players, here is Hélène Loyé, a recruit of a year or three later. In 1862 she was singing leads (Croquefer) at the Bouffes. Mlle Loyé had a voice which might have taken her far, but in 1873 she came back from Toulouse, Rouen and Bordeaux to sing in a reprise of La Faridondaine at the Châtelet. Then at Brussels.

|

| Loyé |

Well, I've got a couple of pictures matched with names but no story, and other pictures with neither name nor story. Just date and theatre. More delving to do ...

I would say definitely a cocotte, this one. But name? Fery, Pery, Piery ...

Here is the list of the girls of the 1863 company, in toto, as given in the Paris press at the start of the season:

Tostée, Saint-Urbain, Zulma Bouffar, Irma Marié, Loyé, Anne Taffanel, Géraldine Bo[u]din (ie Clémentine Boudin, dite Géraldine), L Pelva, L de Ferté, d'Alonde, Desirée, B or E Leclère, J Aaron or Baron (Julia?). Utility ladies ie figurantes Mlles Debar, Ida, Gabrielle, Mathilde, Nathalie, Marie, Louise, Amélie, Julia and Descamps.

Well, here's Geraldine ...

And here's Pelva .. oh! no, that's her husband, who joined the company ('trial comique') at the same time ...

This Mlle Descamps?

Ah! It's not Julia Baron. It's this lady. Mlle ?Alaida Baron. But it looks like Julia. Damme it IS Julia ..

Not too many of the old brigade. Mlle [Elisabeth Anne] Taf[f]anel (star understudy) would be the 'oldest'. She really deserves a proper article ...

And is this 'Louise'?

and this is labelled 'Gabrielle'. Gabrielle Gauthier?

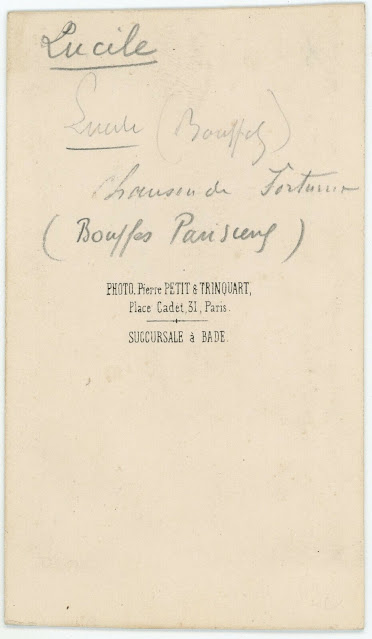

'Lucile' as one of the little clerks in La Chanson de Fortunio

Who knows? More work required.

Here's another Gabrielle. 'of the Variétés' ..

And who are these? Mlle Louisa, Mlle Charlotte, Mlle Augusta ...

I have here an advertisement from a newspaper of 1863, advertising cartes de visites of personalities. Three are said to be 'of the Bouffes'. Mlles Dachet, Louise Lepage and Nattier ar'n't on the list above.

Glancing through this article five years on, I thought 'who and why WAS Mlle Enjalbert'. Well, this is she

Victoire Zélie Félicité ENJALBERT born Paris 2 November 1836, to Jean Enjalbert and his wife Louise Janne née Danet. Comedy pupil of Beauvallet at the Conservatoire (2nd prize 1855). Played at the Vaudeville 1855-8 where I see her as Finette to the Nicette of Abigdon, in 55 Francs de voiture, Les Lionne pauvres &c. In the 1860s, she was engaged at the Odéon and then the Ambigu-Comique (La Poissarde &c), as well as in the provinces, and was well liked. In 1871 (5 August) she had a son to the actor Pierre Théophile PENOT, dit OMER (1826-1895) of the Ambigu, whom she married in 1880.

2 comments:

Hello. I have some pictures of Anna Taffanel if you want. She was born in Bordeaux like Hortense Schneider. She was one of the prettiest girls of offenbach's singers and a good soprano but died quite young.

That would be great! ganzl@xtra.co.nz. Thank you! Kurt

Post a Comment