RICHINGS, Caroline [REYNOLDSON, Caroline Mary] (b Beresford Street, London 13 May 1832; d Richmond, Va 14 January 1882)

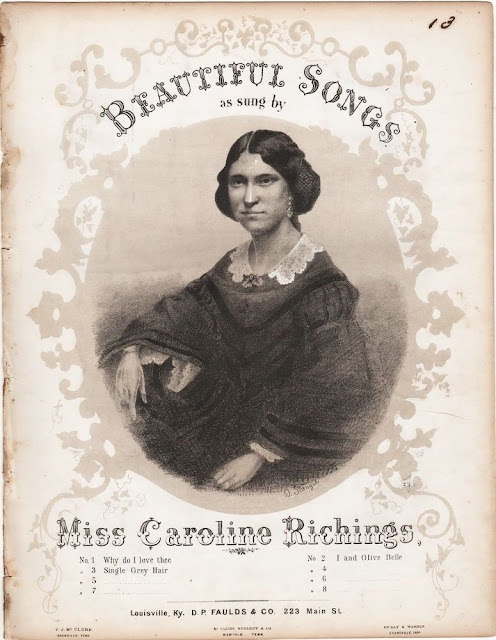

Caroline Richings is remembered as the first important American prima donna to tour opera in English, and to promote native opera, in her home country.

In fact, Caroline was born in Britain, the daughter of playwright and singing actor Thomas Herbert Reynoldson (b Boston, Lincs 31 July 1807; d Hackney, July 1883), at that time playing good roles at Covent Garden, and his wife Caroline Louisa née Fairbrother (m Edinburgh 30 May 1831), but she left England, at the age of 8 months, when her parents emigrated to Pennsylvania (13 February 1833).

The Reynoldsons didn’t stay in Philadelphia. At some stage before 1838, they backtracked to London. In that year Mr R was to be seen at the Surrey Theatre. But they came home without their daughter. Caroline had been ‘adopted’ by the local theatre manager and his wife, and she now became Caroline Richings.

Mr ‘Richings’, just to complicate things further, was also English-born, and not as Richings. He was Peter Puget (b Kensington, x 19 May 1798; d Media, Pa, 18 January 1871), the eldest son of Rear Admiral to-be Peter Puget (d Grosvenor Place, 22 October 1822) of Puget Sound fame, and his wife Hannah née Elrington (d 14 September 1849). He was educated at public school and Pembroke, Oxford (matric: 15 May 1816) and indentured as a law clerk. He clerked in Madras, came home when his father suffered a stroke, and joined the army in the East Indies. That didn’t please, so he came home again, married his Eliza (d Media, Pa 8 March 1880), returned to law, and then – smitten by the theatre world -- quit for good, and while his brothers went on to have honourable careers in the navy, Peter packed up and, 28 August 1821, crossed the Atlantic Ocean to America. Less than a month later he made his first appearance at the Park Theatre, playing Henry Bertram in Guy Mannering.

He played for over a decade at the Park and, latterly, moved into management at the Holliday Theatre, Baltimore, and, after its destruction by fire, the Walnut Street Theatre, Philadelphia. Which is where he encountered the Reynoldson family and their – soon to be his -- little daughter.

The young girl was put to study music with Philadelphia teacher and composer Joseph Plich, and apparently made her first appearance (possibly as a pianist) alongside a Miss Sanson, Camillo Sivori and Henri Herz at the Philadelphia Philharmonic concert of 20 November 1847.

At 20 years of age (9 February 1852), she made her first appearance in opera, playing with the Seguin company and the tenor Tom Bishop in The Daughter of the Regiment at the Walnut Street. It was a role which she would play hundreds of time over the coming years. Less so, James Gaspard Maeder and Samuel Jones Burr’s Washington Irving musical The Peri, or the Enchanted Fountain, which was taken to the Broadway Theatre (13 December 1852) with Caroline (Fluvia), her father and Mr Bishop in the cast. It played twelve performances.

She remained with the Seguin team for a while longer – singing the leading roles in L’Elisir d’amore, La Sonnambula, Linda di Chamonix and surprisingly Norma, but in October Miss Richings put her name above the title for a season of English opera and comedy, featuring The Postillon de Longjumeau, America’s first Louisa Miller and another native work, Mrs Sheridan Mann’s Florentine, or the Pride of the Canton. The lady’s opera was given twice. Over the next years, she appeared in often adventurous opera, comedy, drama -- Ninka in Auber’s La Bayadère (The Maid of Cashmere), Stella in the play The Prima Donna, endless performances of The Daughter of the Regiment varied by Luisa Miller, or Linda di Chamonix, L’Etoile du nord, a season of Italian opera for Maretzek singing Marie, Amina, Elvira (Masaniello), Adalgisa – and apparently in an emergency Azucena – alongside prima donna Mariette Gazzaniga in Philadelphia. Peter Richings was stage director for the season.

The Enchantress was soon added to the list of favourites, and dates at the Walnut, with church choir and concert engagements round the state, a season under the Boucicaults at Burton’s Athenaeum, dates with Leavitt and Allen at Albany, or with Mrs Bowers at the Academy of Music.

In 1859, the Richings went out as stars, playing The Daughter of the Regiment and The Enchantress round the country. They made a first Boston appearance at the Museum in February 1861, and got involved with a little scandal when someone started the rumour that Miss Richings had sung a secessionist song and trampled on the country’s flag. When enough publicity had been culled, Caroline came out with a song ‘The Union Right or Wrong’ (‘her great song’ 'Our Boast is the Union') and the fuss duly faded.

In 1861 she played Auber’s La Circassienne at the Walnut, and in 1862 she returned to New York and Niblo’s Garden (14 April) with the Richings family version of Balfe’s Enchantress (which allowed Caroline to sing ‘Merce diletti amici’ and a whole lot of bits by the show’s md), Auber’s The Syren and The Daughter of the Regiment, The National Guard (which was Auber’s La Fiancée, but got in ‘The Star Spangled Banner’, ‘La Manola’ and a bit of Betly) and, finally, a drastically slimmed The Night Dancers. When they produced Satanella in Buffalo in October 1862, it, similarly, was judged ‘not exactly as Balfe wrote it, but a very fine operatic spectacular drama’.

In 1863, they hit disaster, when their scenery and props were lost in the destruction of Ford’s Theatre, Washington, but they carried on and delivered their repertoire to Philadelphia and dates beyond. 6 April 1863 they produced another new work, The Rose of Tyrol by local composer Julius Eichberg. It might not have been entirely new, as the libretto featured a heroine named Grittly and a hero named Frantz, which would mean it was a remusicked (partly?) version of Le 66. It was voted ‘sprightly and amusing’ and stayed around for a number of years in Caroline’s repertoire.

After two months of starring tour, they returned to Philadelphia with their shows – to which The Bohemian Girl had now been added, and 17 February 1864, another Balfe work, Diadeste.

In 1864, the Richings visited San Francisco for a season at Maguire’s Opera House. The Enchantress was given first (‘Miss Richings’ vocalization fairly took the audience by surprise … we have seldom listened to equal exquisite strains’), and then La Traviata, followed by Satanella, Il Trovatore, and Ernani. At her Benefit she appeared in an allegorical tableau entitled Washington, in which Peter represented Him, and Caroline ‘the Goddess of Liberty’. The general opinion of the season was that the star was fine, the support (including the Bianchis) poor, and the degree of botching of the operas unacceptable. But she stayed on and played on, moving to the Maguire’s Academy of Music with a strengthened company for Lucia di Lammermoor, La Sonnambula, Ernani, The Bohemian Girl, Linda di Chamonix, Norma, Martha, Fra Diavolo, Don Pasquale, another extension with some plays, and then 10 October another opera season, when The Crown Diamonds, Dinorah, Luisa Miller were played, and a new opera by musical director Mr George Evans was announced but, I think, not performed.

The San Francisco episode was apparently a success, and they did not return home until the beginning of the year, for a new season of their repertoire (including The Rose of Castille) at the Arch Street Theatre.

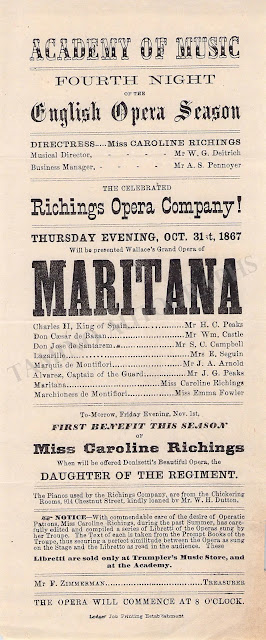

By 1866, Richings had seriously upmarketed his company. He and his star daughter needed better support. William Castle, Sher Campbell. Edward Seguin, Henry Peakes and Zelda Harrison-Seguin provided that support, and the Richings Opera Company could now be dubbed ‘the best organised English Opera troupe we have ever had in this country’, when it returned to Broadway’s Academy of Music 30 December 1867 with The Crown Diamonds, Maritana, Fra Diavolo, Martha, Don Pasquale, The Doctor of Alcantara, Cinderella …

She was not always so clever when it came to hiring artists. Blanche Ellerman, brought from England, sued her after being dropped for lack of talent. And Miss Laura Waldron did the same. Both won. A little more care was taken thereafter, and the Richings banked on second ladies such as Edith Abell and above all, Rose Hersee.

One hiring however had a happier ending. Tenor Pierre BERNARD [BERNHARDT, Peter] (b New York c 1837, d White Sulphur Springs, Va 15 August 1883) and Miss Richings were married in Boston 25 December 1867.

These years were the peak of the Richings company’s achievement, as an all-round fully competent cast introduced Zar und Zimmermann and Crispino e la comare (both adapted by Miss Richings herself), and Das Nachtlager von Granada, but now serious competition emerged in the form of England’s Parepa-Rosa troupe. Miss Parepa was novel and brilliantly talented, Rosa productions were of an excellent standard, and some of Caroline’s key singers deserted to the opposition. Parepa was ‘in’, Miss Richings was old hat, and her operatic rearrangements provincial. She struggled on, until Parepa and Rosa left to return to England, when she recouped her strayed cast, but the motor seemed broken. America had seen Rosa, and no longer rushed to Richings.

For the 1870-1 season, Richings joined forced with the reputable operatic manager Clarence D Hess, and went out with a company of predominantly English principals. They played Les Huguenots, Oberon, The Marriage of Figaro, Bristow’s Rip van Winkle and Lurline alongside their usual repertoire, but on 18 January 1871 Peter Richings died after a carriage accident. The company faded away in the following months, and in May, Bernard and Mrs Bernard were declared bankrupt to the tune of $33,000.

They went to work for other managers. Caroline sang Fidelio with William Castle, Alice in Robert le diable with Karl Formes, then teamed up with James Wallack to play Rosalind in As you like it, Clara in Money, Hortense in The Iron Mask, Diana Vernon in Rob Roy, Henry Dunbar, Daisy Farm, Oliver Twist and Ophelia to Wallack’s Hamlet. She played Rob Roy with Henri Drayton, tried The Enchantress in Boston with a feeble company, tried drama with a stage version of Anna Cora Mowat’s The Mute Singer and, while Bernard went bust a second time, she turned to Old Folks concerts and more weakly-cast essays at her old operas.

Thereafter, the Bernards stayed home, and played largely in Baltimore and in Philadelphia. They performed Les Noces de Jeannette together, Caroline guested for Ford as Little Buttercup in HMS Pinafore and they played in two new little pieces, The Electric Light (25 August 1879) and their own The Duchess (30 July 1880). This latter was played in Richmond, Va, to where the couple had moved to teach music. They appeared at the local Mozart Hall for C L Seigel in some of their lighter repertoire (Les Noces de Jeannette, HMS Pinafore, Billee Taylor, Cox and Box, Doctor of Alcantara, A Night in Rome).

At Christmas 1881, Caroline sang in her local church, but a few days later she was struck down by a virulent strain of small pox, and she died ten days later. Pierre Bernard stayed on in Richmond, but the following year he succumbed to heart disease.

A great deal has been written about Caroline Richings because of her place in the scheme and history of opera in English and the American musical stage. Her life and career were not complex, so it is irritating to find gross errors in published books and, of course, on the web. Especially as the fine historian, Allston Brown, took care to provide a detailed and impeccable obituary of the lady to the Clipper, in 1882, and reprinted it in his own history of the New York stage.

What not a great deal has been written about is her actual performance. Brown tells us she was correct but cool on stage. Which would make her little threat to Parepa. And partially explain her sudden eclipse. The other part seems to me as if it may have something to do with the organising talents of Peter Richings. But I’m guessing. Though Brown makes the same comment. And as far back as 1865, a Californian critic, writing about Adelaide Phillips, had said ‘she excels in that magnetic power wherein Miss Richings so signally failed’.

Caroline and Pierre allegedly had a daughter who became a contralto church singer. I can find no evidence of this child (she is not with her parents in the 1880 census), just a squib in a newspaper announcing Miss Caroline V Bernard singing in a Philadelphia church. So she remains to be proved.

The young girl was put to study music with Philadelphia teacher and composer Joseph Plich, and apparently made her first appearance (possibly as a pianist) alongside a Miss Sanson, Camillo Sivori and Henri Herz at the Philadelphia Philharmonic concert of 20 November 1847.

At 20 years of age (9 February 1852), she made her first appearance in opera, playing with the Seguin company and the tenor Tom Bishop in The Daughter of the Regiment at the Walnut Street. It was a role which she would play hundreds of time over the coming years. Less so, James Gaspard Maeder and Samuel Jones Burr’s Washington Irving musical The Peri, or the Enchanted Fountain, which was taken to the Broadway Theatre (13 December 1852) with Caroline (Fluvia), her father and Mr Bishop in the cast. It played twelve performances.

She remained with the Seguin team for a while longer – singing the leading roles in L’Elisir d’amore, La Sonnambula, Linda di Chamonix and surprisingly Norma, but in October Miss Richings put her name above the title for a season of English opera and comedy, featuring The Postillon de Longjumeau, America’s first Louisa Miller and another native work, Mrs Sheridan Mann’s Florentine, or the Pride of the Canton. The lady’s opera was given twice. Over the next years, she appeared in often adventurous opera, comedy, drama -- Ninka in Auber’s La Bayadère (The Maid of Cashmere), Stella in the play The Prima Donna, endless performances of The Daughter of the Regiment varied by Luisa Miller, or Linda di Chamonix, L’Etoile du nord, a season of Italian opera for Maretzek singing Marie, Amina, Elvira (Masaniello), Adalgisa – and apparently in an emergency Azucena – alongside prima donna Mariette Gazzaniga in Philadelphia. Peter Richings was stage director for the season.

The Enchantress was soon added to the list of favourites, and dates at the Walnut, with church choir and concert engagements round the state, a season under the Boucicaults at Burton’s Athenaeum, dates with Leavitt and Allen at Albany, or with Mrs Bowers at the Academy of Music.

In 1859, the Richings went out as stars, playing The Daughter of the Regiment and The Enchantress round the country. They made a first Boston appearance at the Museum in February 1861, and got involved with a little scandal when someone started the rumour that Miss Richings had sung a secessionist song and trampled on the country’s flag. When enough publicity had been culled, Caroline came out with a song ‘The Union Right or Wrong’ (‘her great song’ 'Our Boast is the Union') and the fuss duly faded.

In 1861 she played Auber’s La Circassienne at the Walnut, and in 1862 she returned to New York and Niblo’s Garden (14 April) with the Richings family version of Balfe’s Enchantress (which allowed Caroline to sing ‘Merce diletti amici’ and a whole lot of bits by the show’s md), Auber’s The Syren and The Daughter of the Regiment, The National Guard (which was Auber’s La Fiancée, but got in ‘The Star Spangled Banner’, ‘La Manola’ and a bit of Betly) and, finally, a drastically slimmed The Night Dancers. When they produced Satanella in Buffalo in October 1862, it, similarly, was judged ‘not exactly as Balfe wrote it, but a very fine operatic spectacular drama’.

In 1863, they hit disaster, when their scenery and props were lost in the destruction of Ford’s Theatre, Washington, but they carried on and delivered their repertoire to Philadelphia and dates beyond. 6 April 1863 they produced another new work, The Rose of Tyrol by local composer Julius Eichberg. It might not have been entirely new, as the libretto featured a heroine named Grittly and a hero named Frantz, which would mean it was a remusicked (partly?) version of Le 66. It was voted ‘sprightly and amusing’ and stayed around for a number of years in Caroline’s repertoire.

After two months of starring tour, they returned to Philadelphia with their shows – to which The Bohemian Girl had now been added, and 17 February 1864, another Balfe work, Diadeste.

In 1864, the Richings visited San Francisco for a season at Maguire’s Opera House. The Enchantress was given first (‘Miss Richings’ vocalization fairly took the audience by surprise … we have seldom listened to equal exquisite strains’), and then La Traviata, followed by Satanella, Il Trovatore, and Ernani. At her Benefit she appeared in an allegorical tableau entitled Washington, in which Peter represented Him, and Caroline ‘the Goddess of Liberty’. The general opinion of the season was that the star was fine, the support (including the Bianchis) poor, and the degree of botching of the operas unacceptable. But she stayed on and played on, moving to the Maguire’s Academy of Music with a strengthened company for Lucia di Lammermoor, La Sonnambula, Ernani, The Bohemian Girl, Linda di Chamonix, Norma, Martha, Fra Diavolo, Don Pasquale, another extension with some plays, and then 10 October another opera season, when The Crown Diamonds, Dinorah, Luisa Miller were played, and a new opera by musical director Mr George Evans was announced but, I think, not performed.

The San Francisco episode was apparently a success, and they did not return home until the beginning of the year, for a new season of their repertoire (including The Rose of Castille) at the Arch Street Theatre.

By 1866, Richings had seriously upmarketed his company. He and his star daughter needed better support. William Castle, Sher Campbell. Edward Seguin, Henry Peakes and Zelda Harrison-Seguin provided that support, and the Richings Opera Company could now be dubbed ‘the best organised English Opera troupe we have ever had in this country’, when it returned to Broadway’s Academy of Music 30 December 1867 with The Crown Diamonds, Maritana, Fra Diavolo, Martha, Don Pasquale, The Doctor of Alcantara, Cinderella …

|

| Sher Campbell |

As ever, ambition was not lacking, as Miss Richings secured the rights to Victorine, Blanche de Nevers, The Desert Flower, The Lily of Killarney … and neither, allegedly, was success: in September it was reported ‘they have cleared over $35,000 in 2 seasons while in England Harrison has failed to make English Opera pay and is reduced to a Benefit’ .

She was not always so clever when it came to hiring artists. Blanche Ellerman, brought from England, sued her after being dropped for lack of talent. And Miss Laura Waldron did the same. Both won. A little more care was taken thereafter, and the Richings banked on second ladies such as Edith Abell and above all, Rose Hersee.

|

| Rose Hersee |

One hiring however had a happier ending. Tenor Pierre BERNARD [BERNHARDT, Peter] (b New York c 1837, d White Sulphur Springs, Va 15 August 1883) and Miss Richings were married in Boston 25 December 1867.

These years were the peak of the Richings company’s achievement, as an all-round fully competent cast introduced Zar und Zimmermann and Crispino e la comare (both adapted by Miss Richings herself), and Das Nachtlager von Granada, but now serious competition emerged in the form of England’s Parepa-Rosa troupe. Miss Parepa was novel and brilliantly talented, Rosa productions were of an excellent standard, and some of Caroline’s key singers deserted to the opposition. Parepa was ‘in’, Miss Richings was old hat, and her operatic rearrangements provincial. She struggled on, until Parepa and Rosa left to return to England, when she recouped her strayed cast, but the motor seemed broken. America had seen Rosa, and no longer rushed to Richings.

For the 1870-1 season, Richings joined forced with the reputable operatic manager Clarence D Hess, and went out with a company of predominantly English principals. They played Les Huguenots, Oberon, The Marriage of Figaro, Bristow’s Rip van Winkle and Lurline alongside their usual repertoire, but on 18 January 1871 Peter Richings died after a carriage accident. The company faded away in the following months, and in May, Bernard and Mrs Bernard were declared bankrupt to the tune of $33,000.

They went to work for other managers. Caroline sang Fidelio with William Castle, Alice in Robert le diable with Karl Formes, then teamed up with James Wallack to play Rosalind in As you like it, Clara in Money, Hortense in The Iron Mask, Diana Vernon in Rob Roy, Henry Dunbar, Daisy Farm, Oliver Twist and Ophelia to Wallack’s Hamlet. She played Rob Roy with Henri Drayton, tried The Enchantress in Boston with a feeble company, tried drama with a stage version of Anna Cora Mowat’s The Mute Singer and, while Bernard went bust a second time, she turned to Old Folks concerts and more weakly-cast essays at her old operas.

In 1875, the couple were hired by Hess, but she was soon back managing herself, and trying to revive The Rose of Tyrol. In 1877 she took a company to California. It was a last hurrah.

Thereafter, the Bernards stayed home, and played largely in Baltimore and in Philadelphia. They performed Les Noces de Jeannette together, Caroline guested for Ford as Little Buttercup in HMS Pinafore and they played in two new little pieces, The Electric Light (25 August 1879) and their own The Duchess (30 July 1880). This latter was played in Richmond, Va, to where the couple had moved to teach music. They appeared at the local Mozart Hall for C L Seigel in some of their lighter repertoire (Les Noces de Jeannette, HMS Pinafore, Billee Taylor, Cox and Box, Doctor of Alcantara, A Night in Rome).

At Christmas 1881, Caroline sang in her local church, but a few days later she was struck down by a virulent strain of small pox, and she died ten days later. Pierre Bernard stayed on in Richmond, but the following year he succumbed to heart disease.

A great deal has been written about Caroline Richings because of her place in the scheme and history of opera in English and the American musical stage. Her life and career were not complex, so it is irritating to find gross errors in published books and, of course, on the web. Especially as the fine historian, Allston Brown, took care to provide a detailed and impeccable obituary of the lady to the Clipper, in 1882, and reprinted it in his own history of the New York stage.

What not a great deal has been written about is her actual performance. Brown tells us she was correct but cool on stage. Which would make her little threat to Parepa. And partially explain her sudden eclipse. The other part seems to me as if it may have something to do with the organising talents of Peter Richings. But I’m guessing. Though Brown makes the same comment. And as far back as 1865, a Californian critic, writing about Adelaide Phillips, had said ‘she excels in that magnetic power wherein Miss Richings so signally failed’.

Caroline and Pierre allegedly had a daughter who became a contralto church singer. I can find no evidence of this child (she is not with her parents in the 1880 census), just a squib in a newspaper announcing Miss Caroline V Bernard singing in a Philadelphia church. So she remains to be proved.

No comments:

Post a Comment