Sullivan's setting of Procter's poem 'The Lost Chord' has been popping up in my daily doings recently. Ezra Read, then Louise Homer ... bringing with it the odd query in my mind... so I investigated a little...

A LOST CHORD

"It may be that only in heaven, I shall hear that great Amen"

One of Arthur Sullivan's best remembered concert songs. And one of the principal reasons that Miss Adelaide Ann Procter makes her way into works of musical, as opposed to poetical, reference to this day.

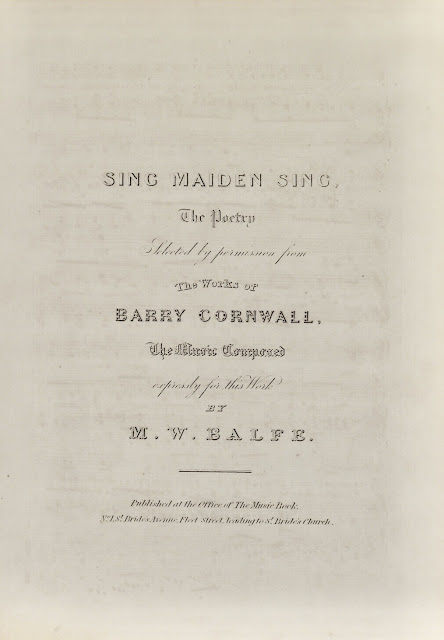

Miss Procter was the daughter of well-known writer 'Barry Cornwall' (Bryan Waller Procter): 'delicate' 'doomed', who moved in the more obvious Sapphic circles, a Catholic convert, and a fluent writer of verse in the mostly sentimental, religious vein of the time, a genrewhich brought her an enormous popularity with the magazine and poetry-buying public.

The poem entitled 'A Lost Chord' was first published in the March 1860 edition of the short-lived English Woman's Journal, and the following year it began appearing, reprinted, in provincial newspapers in Britain --the Northampton Mercury, The Leicester Chronicle, Trewman's Exeter Flying Post, The Dover Express et al -- and America, as well as being included in Miss Procter's second volume of Legends and Lyrics (1861).

It seems to have been set to music for the first time in 1864, appearing within months in different versions on each side of the Irish sea.

The English one comes from Exeter

William Pinney (1845-1906) was a local lad, the son of an elder William Pinney (b Shute 17 August 1808; d Exeter 18 June 1879) who had been a trumpeter in the devon Yeomanry, a sergeant in the Devon militia, and who played for forty years in the Exeter Theatre orchestra while running the Eagle Inn in Barrack Lane. William jr was set to music at an early age, and in his teens was assistant organist at Exeter Cathedral. He would go on to be organist at Sidmouth and Ramsgate, earn a Mus Bac at Oxford (1880) and become long time organist at St George's, Hanover Square (1876-1892). Here, still in his teens, he turned out his version of Miss Procter's verse: alas, I cannot find a copy. Whether it were first published by Mr Smith or not, it was smartly picked up by Boosey ... Pinney's 'fame' however rests on his second daughter, Beatrice May Pinney, long-term mistress of Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree and mother of a number of his children.

The Irish version can be spotted in May 1864, sung by basso Richard Smith of Dublin, but when it was published, it didn't receive such a kindly welcome. The Musical Standard took a hatchet to, especially, the poetry ...

They were clearly not the only musicians to have a go at the words: when Montem Smith sang one of these (I suspect the Robinson) at the Bury Athenaeum (1865) the local press sniffed that the words had been 'set to better music by a local amateur'. And in 1865 I spy a version by G A Macfarren published by Metzler, and one by Simon Waley (Lucas, Weber & Co).

Bessie Palmer sang the Robinson version at several concerts, including her own 5 June 1865 and Miss Berry Greening's in February 1866, Fanny Poole also took it up, and I would guess that most of the uncredited amateur performances in the later 'sixities were of the Irish setting.

Boosey, Metzler and Lonsdale each had their 'Lost Chord', so Chappell had to join the band. At the end of 1870, they turned out a version by one 'Anne Hall' 'pupil of W T Wrighton'. The 'devoted student' may or may not have existed, I can find no other trace of her, but the Musical Standard rubbished her piece completely: 'Her knowledge of composition is evidently extremely limited -- so limited indeed that we cannot recall any song the contains greater errors in the harmony or more singular mistakes in the notationn'. Neither did he spare the lyrics. 'Miss Adelaide Procter has written some good lyrics [...] but "The Lost Chord" which sounded like "a Great Amen" is not one of them. It is not adapted to music, unless the composer have a taste for the ridiculous ...'

Strange, then, that so many song writers had chosen to set these 'ridiculous' words? And it was not over yet. In 1875, while Miss Churcher of Southampton, Miss Greer of Belfast, Miss Wood of Gravesend, Mrs H Freeman of Bicester, Miss Hemming of Droitwich e tutti quanti were giving their Great Amen at amateur concerts, composer and music publishers John Blockley (b Westminster 5 July 1801; d 6 Park Rd, Hampstead 24 December 1882) produced his version

|

| Charlotte Sainton-Dolby |

Lonsdale annouced a reprint of the Robinson for its circulating music library 'as sung by Madame Sainton Dolby', Chappell kept the Hall version doggedly on its lists -- though apart from a Miss Dilke at Nuneaton no one seemed to sing it -- the Blockley and the MacFarren did better: I see the latter sung by Miss Coyte Turner; and both made their way to the Antipodes ... and after a little more than a decade it seemed that the "Great Amen" would finally be put to sleep.

But, as we know, that wasn't to be. Quite what inspired Arthur Sullivan to take up a not-very-well noticed text, for the umpteenth time, I know not. The story I was taught at Dame Rumour's knee was that the poem was set in mourning for the death of his brother, Fred. Fred died 18 January 1877. Sullivan's version was sung in public for the first time on 31 January 1877. Quick work. We are also told that it was 'written for' the American contralto Antoinette Sterling of the Boosey Ballad Concerts. Perfectly probable: professionally, versions of the song had been sung principally by a low voice, and almost always a contralto, even of the quality of Miss Palmer and Mrs Poole. The business arrangements of the bringing out of the song had, anyway, had time to be arranged. Apparently Dr Sullivan and Miss Sterling each got 6d per copy of sheet music sold. I imagine that, for that emolument, she was obliged to sing the song a specified number of times. She sang it countless times.

|

| Fred |

The arrangement was obviously not secret: the practice was widespread. However the London correspondent of one of America's squeamiest rags The Chicago Tribune (a certain Charles Landor) decided to make himself a namelet and reported: 'The music is in my opinion of the most indifferent, monotonous character and I thought that this original singer displayed some disgust at the advertising trick which made it part of her performance'. I presume that he was meaning the money things rather than Sullivan's family grief. But with the Chicago Tribune ... who knew? I don't think Madame Sterling would have been 'disgusted' with her royalty. One report which I have read estimated that 'The Lost Chord' sold 25 million copies... and that was in the nineteenth century!

'The Lost Chord' as sung by Miss Sterling at St James's Hall, accompanied on the harmonium by J W Elliott, on 31 January 1877 was immediately a decided hit. Song and singer were admirably suited, and Boosey programmed the piece liberally through the season of the London Ballad concerts, sung each time (and contractually) by Miss Sterling. If it were a piece of song-plugging .. and the Boosey concerts were, naturally, that .. it surely worked. And that wasn't always so. Helen Lemmens-Sherrington's attempt, for example, to launch 'The Liquid Gem' was a memorable failure. At the Boosey concerts, they plugged as hard as they could, but many were the songs introduced by Sims Reeves, Santley, Miss Sterling, Madame Lemmens and other concert stars which were folded away after their first season.

Not this one. In spite of the odd snooty critic ('the melody recalls Mrs J W[orthington] Bliss's well known (sic) Bridge'), during the years that followed just about every top contralto in Britain -- and even some fine but inappropriate sopranos or baritones -- had a crack at Sullivan's version of the perhaps unjustly scorned words. I have picked up (in order of up-picking), during the song's first twelvemonth out, Florence Winn, Mrs Bradshaw(e) Mackay(e), Mrs Osborne Williams, Fanny Poole (abandoning the Robinson), Edith Wynne, Emily Dones, Fanny Danielsen-Ashton, Helen(e) D'Alton, Martha Harries, Elizabeth Mudie-Bolingbroke at the Leeds Festival, Lena Law, Fanny Robertson, Alice Fairman, Annie Butterworth, Fanny Edwards, Julia Derby, Mary Cummings, Cola Schneegans, Florence Rice Knox ... as well as uncountable amateur ladies throughout the country and the colonies ... and a few men, particularly of the Reverend persuasion (Rev Cole-Hamilton of Northampton, Rev Amcotts-Jarvis of Lincolnshire, Rev T Everett et al), and even a Master Charlie Davis of Oswestry and a Master C Pugh of Wrexham. The treble versions can hardly have been as ludicrous as Mr W H Jude's. The gentleman presented an Entertainment at Liverpool, backed by 20 singers from the Edgehill Vocal Society. He sang 'Cheer, boys, cheer', 'From Rock to Rock', the Judge's song from Trial by Jury ... and 'The Lost Chord'.

In spite of Chicago's attempt at sabotage, the song made its way swiftly to American concert-rooms .. I see Herietta Beebe performing it before the year was out, and a Mrs C P Whitney of Virginia ... then Mrs Knox again, Emily Winant and others ..

America, too, produced its own versions of Procter's poem, of which this one has survived

Sullivan's success didn't prevent other folk from trying to cash in. Music publisher/songwriter William M Hutchinson, 'composer of 'Dream Faces' and 'When the Children are Asleep', produced (under the pseudonym of 'Julian Mount') and published (under the pseudonym of 'William Marshall & Co') round about 1882

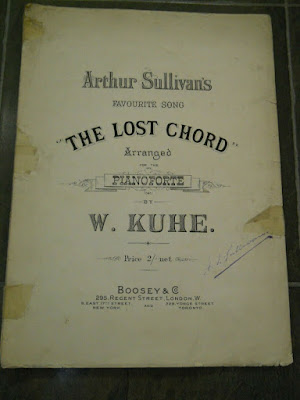

At some stage Procter's words were glued to some homogenised Beethoven, and then of course came the 'arrangements' of Sullivan's music promoted by Boosey. William Kuhe (1877) for the piano ..

Dr William Spark, who had played the organ part in the voice/piano/organ version arranged the piece for organ,

there were 'versions' for brass and wind, for strings and squeeze-boxes, and there were parodies

and one H W Petrie of the iconoclastic US of A, and composer of 'Asleep in the Deep', perpetrated an 'answer' to Miss Procter's poem under the title 'The Lost Amen'.

In the century and a half since Miss Procter penned her words, and a little less since Fred Sullivan died and his brother penned his music, 'The Lost Chord' has been more or less permanently on the music stands of the world. It has been recorded and recorded, voices other than that for which it was intended have adapted it to their ranges with usually less rather than more effect, I have heard it played by a brass band, described as a 'hymn' ... and, yes, I sang in myself in the 1960s. Well, who can resist 'It May Be That Death's Bright An-gels ...'? Almost as stentorian as Hahn's 'Invictus' ...

Of all the triumphant and enduring songs to have been introduced at the famous Boosey Ballad Concerts, I think 'The Lost Chord' may claim to be the most triumphant and the most enduring. But, nevertheless, I should love to hear all the others ... Anyone got a Pinney?

1910 recording of Sullivan's version ... in two parts! I wonder who hid behind the pseudonym of 'Alice Craven'.

2 comments:

Beginning to think that the Musical Standard just wasn't a fan of the poem. From March 14, 1868, p.115:

"A LOST CHORD."

Song written by Adelaide A. Procter.

Composed by William Pinney. London: Boosey & Co.

THESE words, as our readers may recollect, have been

set before, not with signal success if we remember aright;

in point of fact every additional setting helps to prove

that if the said words do mean anything it invariably

escapes the composer. But do they in reality mean any-

thing?- did "Barry Cornwall's" clever daughter clearly

know what she was writing when " A Lost Chord" was

committed to paper? We incline to think her idea--a

beautiful one in itself-was very inaptly expressed, and

that she desired to convey something quite different from

the notion of a big chord, like "a loud amen" played

upon the organ (the "amen " is at least two chords, by

the way). However, composers seem to be charmed with

the verses, and they try very hard to set them to appro-

priate music. Mr. Pinney we imagine to be inexperienced

in composition, but he has evidently done his best, and

some of his phrases are decidedly well conceived. There

are several errors of notation which should be corrected,

as, for instance, at the word pain upon page 4, where the

a natural should be b double flat – the natural note being

in reality a minor ninth to the bass.

https://books.google.com/books?id=9zw0AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA115&lpg=PA115&dq=%22William+Pinney%22+%22lost+chord%22&source=bl&ots=nR-CNs-jX3&sig=ACfU3U04TPumRT5VtFRuyJINBF9sOQe5-A&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj7nIWhnY31AhWGgGoFHQ5_Dz8Q6AF6BAgCEAM#v=onepage&q=%22William%20Pinney%22%20%22lost%20chord%22&f=false

Did any of these compositions attempt to replicate the chord itself?

Post a Comment