Wednesday, July 31, 2019

The Gänzl Post Facebook Rejected

Ladies Surfing Championships, 3 and under 5 class

Swimsuit not obligatory ...

O what twisted minds lurk behind the facade of facebook ...

And what hypocrisy ...

Sunday, July 28, 2019

Faking Francesco: a cross-eyed curriculum vitae

'When there's fac-t-ual researching to be done, An historian's life is not an easy one (chorus: 'easy one')'

Especially where showbusiness is concerned. It's difficult enough to track down reports, reviews, announcements and so forth from a century or two ago, but when folks -- for one reason or another -- deliberately strew the pathway to truth with purposeful fabrications and lies, well, even for an old truffle-hound such as I, it is a tricky and time-consuming job to deconstruct the web which they have woven.

And 'web' is a meaningful word, here. In the age of the Internet, folk no longer do their own research. They cut and paste, here and there, without pausing to care whether their 'source' is reliable or truthful.

I'm prompted to this animadversion by the article that follows. I wrote it some years ago, but I found it again this week, during a tidy up in my archive. It is really an article about an article. One of the more blatant attempts at fakery that I've encountered over the years. That piece of fakery is now all over the web, translated into a number of languages, and only Wikipedia has thought to question some of phoney facts therein. So, here it is. The history of the baritone Francesco Mottino (and wife). The fake version, and my version.

MOTTINO, Francesco (b Cuorgnè, Piedmont c1833; d Milan 11 February 1919)

It is a curious fact that a number of exceedingly average Victorian vocalists have gone down in ‘history’ with glorious adjectives and lush ‘facts’ undeservedly attached to their names. Usually these ladies and gents had something to do with America. Either they were Europeans who had thence emigrated and fooled the locals into believing a golden past (one thinks immediately of Ugo Talbo and Ernest Perring), or they were hometown folk who had gone to Europe, sung a few roles in minor Italian houses, and come home as ‘prima donna, La Scala’ to teaching and lavish obituaries. But the baritone Francesco Mottino (in spite of all temptations by the press to make him English) was a real Italian. So why is he one of the worst examples of all? Why is he even in Kutsch and Riemans? And why does Wikipedia think him worthy of its attention? And, yes, both articles are taken from the same source. I’ll tell you what I think. In his later years, Signor Mottino set up in Milan as a teacher of operatic aspirants. He didn’t teach them singing. He taught them acting. And the girls and boys from Boston (and even Sydney, Australia) went home and related how they’d been having lessons with this ‘famous’ teacher, ‘famous actor’ (the name of Salvini was mumbled), and so Signor Mottino became ‘famous’ in Boston and Sydney, Australia, while at home he was just another one of those teachers who preyed on gullible wannabes, and himself was a writing wannabe, with a heap of unset operatic libretti in the cupboard, and a bundle of self-published poetry.

So, lets have a look at this article (undoubtedly ‘made in America’). ‘Francesco Mottino was an Italian opera singer, voice teacher, drama teacher, librettist and writer. He had a prolific international opera career from the 1850s through the 1870s. After retiring from the stage, he worked actively as a writer and teacher in his native country’.

Well, that doesn’t say much. Except the ‘prolific international’ career. As far as I know, he performed only in Italy and the United Kingdom. And not a lot of the latter. And perhaps Croatia.

‘As a child, Mottino was a student of many languages and became a highly proficient writer and speaker in English and French at a young age. He began his career as writer for magazines and also performed on the Italian stage in plays by William Shakespeare.

OK, so he was a penny-a-liner, and did an amateur Shakespeare. But the good English is a fact, and was the cause for the later rumours on his nationality.

‘He became interested in opera and entered the Milan Conservatory in 1855’. Somewhere, it is said that he debuted in Zadar in 1855.

‘Mottino began his opera career performing in smaller baritone roles at various Italian theatres while still a pupil in Milan. During the 1860s, he performed in leading roles in operas in France, Belgium, Switzerland, Greece, Turkey and Egypt in addition to appearing at many of the principal Italian theatres. He was particularly known for his portrayal of the title role in Giuseppe Verdi's I due Foscari, a role he sang at many opera houses’.

Well, I can’t find any of that imprecise stuff. I see him in Pavia in 1861. Cesena and Modena in 1864, at a Genoese theatre in 1865, in Enrico Bernardi’s Faustina at Lodi, Les Huguenots at Messina in 1866, at Mantua, Vercelli, the Teatro Armonia in Trieste, at Como, Palazzolo sull’ Oglio and Brescia … the principal theatres of Italy? In 1870, I spy him at the Pagliano in Florence, singing Fontanges in Il Cadetto di Gascogne.

But now we get into the ‘easy to check’ area, which is also the laughing out loud area.

‘He reached the pinnacle of his stage career in England during the 1870s where he performed frequently at both the Royal Opera House and at Her Majesty's Theatre. He also often appeared in London concerts, including several performances with soprano Adelina Patti at The Crystal Palace. He was the leading baritone of the Carl Rosa Opera Company from 1875–1879 and toured with that company to many British cities.’

Almost totally false. He never sang with either Italian opera (I assume by Royal Opera House, the Covent Garden Theatre is meant), unless in the chorus or under another name, he rarely appeared in concert in London, he didn’t sing several times at Crystal Palace with Adelina Patti -- though he appeared with Lemmens-Sherrington and got noticed as 'a second rate Italian baritone [who] proved his inefficiency’ in ‘Di provenza’ and the brindisi from Il Guarany -- and 25 May 1872 was on a bill that featured Santley and Carlotta Patti -- and he sang with the Rosa not for four years, but more like four weeks.

So, what did he do at this ‘pinnacle’ of his career. He sang at the Crystal Palace on 25 May and 12 October 1872, he sang at the Surrey Gardens 11 July, and he made what seems to have been his only London opera appearance in a short subscription season at St George’s Hall (10 December 1872), put together by the ageing Monari-Rocca with a curious cast of what I can only assume were friends. Mottino sang Figaro, Belcore and Guglielmo in Cosi fan tutti, was adjudged probably the best of the very weak group, and later repeated his Cosi for one Benefit performance at the St James’s Theatre.

In August of 1873, he joined a rather better company (with Monari) for a brief season in Dublin, playing Figaro, Luna and Valentine, and then came the Rosa engagement. It was a very nice engagement, and, historically, Mottino comes out of it well. He was the first principal baritone of the soon to be famous Carl Rosa Opera. The company opened at Manchester, and proceeded to Bradford and Sheffield, with Mottino playing Luna to the Leonora of Pauline Vaneri, Valentine in Faust and the title-role in Don Giovanni … The next stop was Liverpool, and by Liverpool Mottino was gone. Sher Campbell was now Don Giovanni. Mottino had ‘toured’ three British cities.

So, on we go. ‘Among the roles for which he was praised by London audiences were the Count di Luna in Il Trovatore and the title role in Rossini's William Tell. He also starred in the world premiere of Lauro Rossi's Biron on 17 January 1877 at Her Majesty's Theatre.’

No he wasn’t. He never played either operatic role in one of the Opera Houses of London. And Rossi’s disastrous vanity production of the Macbeth-like Bjorn (not Biron), at the second-string, off-West-End Queen’s Theatre (no way, Her Majesty’s) was not something that one would want to boast about being connected with! Although he personally got quite well noticed as the Norwegian king.

In August of 1873, he joined a rather better company (with Monari) for a brief season in Dublin, playing Figaro, Luna and Valentine, and then came the Rosa engagement. It was a very nice engagement, and, historically, Mottino comes out of it well. He was the first principal baritone of the soon to be famous Carl Rosa Opera. The company opened at Manchester, and proceeded to Bradford and Sheffield, with Mottino playing Luna to the Leonora of Pauline Vaneri, Valentine in Faust and the title-role in Don Giovanni … The next stop was Liverpool, and by Liverpool Mottino was gone. Sher Campbell was now Don Giovanni. Mottino had ‘toured’ three British cities.

So, on we go. ‘Among the roles for which he was praised by London audiences were the Count di Luna in Il Trovatore and the title role in Rossini's William Tell. He also starred in the world premiere of Lauro Rossi's Biron on 17 January 1877 at Her Majesty's Theatre.’

No he wasn’t. He never played either operatic role in one of the Opera Houses of London. And Rossi’s disastrous vanity production of the Macbeth-like Bjorn (not Biron), at the second-string, off-West-End Queen’s Theatre (no way, Her Majesty’s) was not something that one would want to boast about being connected with! Although he personally got quite well noticed as the Norwegian king.

He did, actually, fulfil one more operatic job in England. In 1876, a striving touring opera troupe was put together as ‘the Imperial Opera Company’ with Madame Laville Ferminet as prima donna. They played a few dates in November, with Mottino repeating his Luna and Valentine, before he went off to play Bjorn, (‘newly arrived from Naples’), after which he returned to the tour (La Traviata, Il Trovatore, Rigoletto, Le Nozze di Figaro, Faust, Don Giovanni) until it ground to a halt in Dublin in April. And that was the end of Signor Mottino’s pinnacle. A hundred other Italian baritones of the era had done decidedly more and much, much better.

Back in Italy, he tried for a few more years (Cremona, Turin, Reggio Emilia), and is said to have ‘retired’ in 1880.

‘Mottino retired from the stage in 1880, returning to Milan that year with his wife, soprano Adele Cesarini, with whom he had often performed’. English-born Miss Cesarini seems to have retired before her husband. I don’t see her out after the 1860s.

‘From 1880-1887 he ran the literary magazine L'Utopista, working as both the magazine's editor and a contributor of articles … In addition, he taught singing and acting in Milan for several decades’. The acting we know about. And ‘L’Utopista Giornale letterario, artistico, politico, sociale. Dir: Francesco Mottino’ is a fact.

He also pursued his strenuous libretto-writing, and a couple of his pieces reached the stage. A one-act Il Conte di Salto (music: Giovanni Consolini) played at the Teatro Chiabrera in Savona 21 January 1894, and Il Fuggitivi was given a semi-professional production at Trento 11 April 1896.

Mottino’s passing may have been noticed in Milan. Probably not. But it was in America.

‘Word has reached America that Francesco Mottino, one of the most famous of Italian actors in his day, and, in his retirement, among the most prominent teachers of singing, passed away at his home in Milan on February 11 1919, in his eighty-sixth year’.

A famous actor? Ah well. That’s how to invent history. I hope I have now un-invented it.

CESARINI, [Mary Ann] Adelaide (b London 3 May 1829; d unknown)

I have been able to track down the whatever-became-of of many of the momentary and mini-starlets of the British music scene, but Mdlle Cesarini eludes me.

Back in Italy, he tried for a few more years (Cremona, Turin, Reggio Emilia), and is said to have ‘retired’ in 1880.

‘Mottino retired from the stage in 1880, returning to Milan that year with his wife, soprano Adele Cesarini, with whom he had often performed’. English-born Miss Cesarini seems to have retired before her husband. I don’t see her out after the 1860s.

‘From 1880-1887 he ran the literary magazine L'Utopista, working as both the magazine's editor and a contributor of articles … In addition, he taught singing and acting in Milan for several decades’. The acting we know about. And ‘L’Utopista Giornale letterario, artistico, politico, sociale. Dir: Francesco Mottino’ is a fact.

He also pursued his strenuous libretto-writing, and a couple of his pieces reached the stage. A one-act Il Conte di Salto (music: Giovanni Consolini) played at the Teatro Chiabrera in Savona 21 January 1894, and Il Fuggitivi was given a semi-professional production at Trento 11 April 1896.

Mottino’s passing may have been noticed in Milan. Probably not. But it was in America.

‘Word has reached America that Francesco Mottino, one of the most famous of Italian actors in his day, and, in his retirement, among the most prominent teachers of singing, passed away at his home in Milan on February 11 1919, in his eighty-sixth year’.

A famous actor? Ah well. That’s how to invent history. I hope I have now un-invented it.

CESARINI, [Mary Ann] Adelaide (b London 3 May 1829; d unknown)

I have been able to track down the whatever-became-of of many of the momentary and mini-starlets of the British music scene, but Mdlle Cesarini eludes me.

She was born in London, the daughter of an Italian immigrant, Baldasar Emilio Vincenzo Cesarini, who at various times ran an Italian warehouse, a dining house and a macaroni and oil bazaar, and was apparently coached in music by Bottesini, who accompanied her on her public debuts (10 July 1853) at Mlle Staudach and Antonio Bazzini’s concert, and (10 October 1853) at an Italian charity concert (‘Di piacer’). ‘A young vocalist of very remarkable promise’ noted the press.

She appeared at several more Italian connected concerts in 1854, as well as singing ‘Regnava nel silenzio’ with the London Orchestra, ‘O luce di quest’anima’ at a hospital benefit (‘star among the vocalists’) and at Madame Puzzi’s (‘Mdlle Cesarini, who gave the cavatina from Linda with remarkable sweetness, is fast rising in public esteem’) and looked to be establishing for herself a position among the young sopranos of the day.

She seems, then, to have disappeared to Italy where she was engaged by a certain Domenico Ronzani, some time the lead dancer and ballet master at the Italian opera – said to be a family friend – to appear as Fenena in Nabucco at the Teatro Regio, Turin for Carnevale of 1856-7. She was a disaster: ‘la Cesarini la quale inceppata sulla scena, disse la preghiera in modo da far ridere il pubblico’.

During this period, apparently, her mother died (presumably in Italy, for the fact is not registered in Britain) and she returned home. Ronzani hired her again, in London, for a season of opera buffa at the St James’s Theatre. She appeared as Serafina in Il Campanello, as an afterpiece, and was judged to have ‘a pleasing and agreeable countenance, is very ladylike and has a fresh, well intoned and agreeable voice’. However, Miss and/or Signor Cesarini was not happy. Ronzani hadn’t actually paid the little soprano. So she went to court.

Ronzani disappeared back to Turin and thence, in 1857, to America where he died 13 February 1868, Vincenzo Cesarini had already died in 1859 … and Adelaide, for a while, eluded me. She didn’t stay in England … so I didn’t suppose I would ever track her down.

But I did. ‘Adele Cesarini [Mottino]’ resurfaces in Italy as a leading soprano at various mostly lesser provincial theatres in the 1860s and 1870s (Il barbiere di Siviglia, Il furioso all’isola di San Domingo, Torquato Tasso, Marguerite in Les Huguenots). During that time, she married the baritone Francesco Mottino and, I imagine, therafter lived happily ever after.

Tuesday, July 23, 2019

The Wakefield Musical Festival

.

This is another wee treasure. I knew what it was, the moment I saw it on e-bay. Yes, it's a prize medal, allegedly from 1893, from what has been claimed as the first competitive Eisteddfod in Britain. And it did not take place in Wakefield, as in Yorkshire, it took place in Kendal, Westmoreland. The 'Wakefield' part came from the name of the founder of the event: contralto Miss Mary Wakefield. Miss Wakefield was a very superior amateur vocalist ... but, here, read all about her and her career and her competition, in this little piece I wrote a year or two ago for my Victorian Vocalists:

This is another wee treasure. I knew what it was, the moment I saw it on e-bay. Yes, it's a prize medal, allegedly from 1893, from what has been claimed as the first competitive Eisteddfod in Britain. And it did not take place in Wakefield, as in Yorkshire, it took place in Kendal, Westmoreland. The 'Wakefield' part came from the name of the founder of the event: contralto Miss Mary Wakefield. Miss Wakefield was a very superior amateur vocalist ... but, here, read all about her and her career and her competition, in this little piece I wrote a year or two ago for my Victorian Vocalists:

WAKEFIELD Mary [Augusta](b Kendal 19 August 1853; d Nutwood, Grange over Sands 16 September 1910)

It’s my self-imposed rule for this collection that I don’t ‘do’ people who’ve already had a whole biography devoted to them by someone else. But the splendid little memoir of Mary Wakefield published in Kendal by Rosa Newmarch (1912) probably didn’t get far beyond Westmoreland, and in any case it deals largely with the woman and her achievements rather than her singing career.

Miss Wakefield was an amateur. Probably – along with ex-professional Nita Gaetano (Mrs Lynedoch Moncrieff) – the outstanding amateur vocalist of her time and place. She was an amateur not because of any lack of skill, but simply because the wealth and position of her family meant that she had no need to become professional. And thus, she spent the whole of her career singing, principally, at those frequent ‘charity’ concerts, fetes, bazaars etc mounted by the aristocratic, the highly-social and the wealthy, at first in her home area, later in London, and eventually all around Britain.

Mary was one of the seven children of Mr William Henry Wakefield of Sedgewick House, Kendal, banker, JP, sometime Mayor of Kendal, High Sheriff of Westmoreland and ‘enormously wealthy’ and well-connected, and his wife Augusta Catherine née Haggarty, whose father was at one time US consul in Liverpool.

Miss Newmarch relates how she studied voice at school, in Brighton, with Ercole Mecatti, and subsequently in London with Randegger, and made her first appearance in a public concert in 1873 in a local charity affair staged by her aunt. I spot her first in 1876 (2 June) at that mecca of the society amateur, Grosvenor House, singing contralto in one of the Misses Robertson’s church-roof concerts along with such ubiquitous inhabitants of such occasions as Charles McCheane and Charles Wade.

In 1877, I see her singing Hercules alongside Lady Agneta Montague, Lionel Benson, the Hon Spencer Lyttelton, Countess Cowper, and her friend Miss White, with the Guild of Amateur Musicians, and in 1878 at Kendal, Worksop, Chester et al, in the company of the well-known Major Simmons or Sir George Cornewall, as well as in more functions at Grosvenor House.

She touched on the professional world (Gertrude Cave-Ashton, Harper Kearton, Thomas Brandon) when she sang the contralto music in Joshua at Morecambe (1878) or Eli at Lancaster with Catherine Penna, Redfern Hollins and Cecil Tovey, but mostly she appeared at amateur or perhaps society semi-pro occasions where she shared a platform with such as the Henschels and Charles Santley as well as Mrs Ronalds, Theo Marzials and other socialites (‘Roeckel’s ‘The Vision of Years’,’Rendimi al cuore’, ‘A best yet present’, ‘Darby and Joan’, ‘Sleep dearest sleep’, ‘Cangio d’aspetto’, ‘The Sands of Dee’, ‘When the children are asleep’, ‘Cherry Ripe’, Mignon gavotte, &c).

In 1880, she was engaged to sing in the Three Choirs Festival at Gloucester. Her contribution was small, but it included the contralto music in Leonardo Leo’s Dixit Dominus, and she was praised for her ‘beautiful voice and well-ordered method’. She sang The Messiah at York, with Mary Davies and Edward Lloyd, appeared at St James’s Hall with Marzials in the Boosey Ballad concerts (16 March 1881) and repeated the Dixit Dominus at St James’s Hall with Anna Williams. But she apparently decided not to go that way, and returned to singing in society concerts, at the country homes of the rich and aristocratic, and with local societies, with only the occasional foray into provincial oratorio (Samson at Lancaster, St Paul at Exeter).

At the same time she had her first successes as a songwriter. She had been composing songs since 1875, but now she published ‘A Bunch of Cowslips’ aka ‘Polly and I’ and ‘No Sir’, both of which were to become concert favourites. Others, such as ‘Shearing Day’ and ‘Moonspell’ would follow.

By the end of 1883, a provincial paper could rightly aver that Mary and Nita Moncrieff ‘stand quite at the head of lady amateur vocalists’, adding that Miss Wakefield ‘excels in the semi-humorous, semi-pathetic style’.

She continued her society vocalising through the 1880s, still stepping out occasionally to sing with the professionals at Charity Dos, in the odd oratorio (Elijah with Mary Davies, Hirwen Jones, Thorndike in Belfast, Lobgesang with Mrs Hutchison and Ben Davies in Rotherham) and made quite a stir when she delivered the whole of Schumann’s Frauenliebe und leben in London and the provinces. In 1894 she performed Die schöne Müllerin and Frauenliebe in a programme at Prince’s Hall. In the1890s she was seen round Britain lecturing on ‘Scottish Melodies’, ‘English National Melodies’ and other such topics which allowed her to sing some 20 songs in an evening.

Amongst her other activities, she established in 1885 and ran thereafter, with her sister Agnes Argeles, the [Mary] Wakefield Music Festival in Westmoreland, on the lines of the Eisteddfods. Miss Newmarch claims this as the first instance of a competitive festival in Britain. The Festival in held, bi-yearly, to this day (www.mwwf.org.uk/)

.

Struck by poor health, Mary Wakefield largely ceased her musical activities in 1900, but she lived on till 1910 when she died in her home in Westmoreland aged 57.

Birmingham Festival 1867: team photo

.

This has got to be my favourite item from my morning trawl on e-bay. A composite team-photo of the stars of the 1867 Birmingham Festival. But who, I pondered, was each person. I am not very good at identification, but nevertheless, even I could pick out Charles Santley, Sims Reeves, and Willoughby Weiss at the extreme right. And Christine Nilsson, centre front.

That left Therese Titiens, Helen Lemmens-Sherrington, Janet Whytock-Patey and Charlotte Sainton-Dolby ... presuming that Arabella Goddard missed the photo call... well, it must be Patey behind the piano, Dolby at the left and Sherrington at he right, but that doesn't look like Titiens in black! Shuffle and cut again ..

And the men? Well, W H Cummings is there somewhere, it must be he looking as if he's seven feet tall, next to the other singers ... oh, I know some of those faces so well, but ... is that Sterndale Bennett with his hands on his hips? His Woman of Samaria had its first performance during the Festival. That's Costa looking pompous, behind la Nilsson, yes? And there's no mistaking Julius Benedict, next to Bennett ..

Well, the National Portrait Gallery tells me that ones I haven't pinned are J F Barnett, Prosper Sainton, the organist James Stimpson and Cummings. But that only makes a total of ten, and there are eleven chaps in the photo. Who is missing? W G Cusins, perhaps, who conducted the premiere of The Woman of Samaria? Ah! Here's a little story ...

So, it looks as if it is indeed Cusins who is our spare man. And Miss Goddard didn't hang around to be photographed.

Well, I'll post this on facebook, and in half an hour I'll have all the answers!

SHORTLY AFTER. Australia was awake! And after mature discussion we have come to the following conclusion. Left to right.

Barnett, W G Cusins with the muttonchops, Sterndale B, Benedict, Stimpson at the keyboard, Janet Whytock, Prosper Sainton looking splendid, Costa looking Costaffective, Sherrington in black, Santley, Reeves, Weiss .. and seated Titiens looking remarkably svelte, Nilsson, and Dolby. OK?

Sunday, July 21, 2019

An Irish Oratorio: 1824.

.

I am no longer a Collector. Oh, I was, once ... rabidly. When younger. Music, theatre programmes, libretti, photographs, ephemera, recordings ... all the stuff that went into the making of my early multi-volumes books. But then I stopped. And what had been 'Kurt Gänzl's British Musical Theatre Collection' now nestles, courtesy of Dr James Ward, in the Harvard University Theatre Library. Some twenty years later, I wonder if the whole lot is catalogued!

Anyway, all that as a prelude to saying that the urge to acquire doesn't wholly go away. Every so often, in a shop or, these days, on e-bay and its ilk, I spy a little gem. Usually something ancient, from the narrowest part of my area of expertise ... and just about nobody else's! ... and of which, thus, nobody else knows the significance. And, thus, nobody cares much about. Excepting myself. Well, this week it happened. Here is the item. I know. Only I would get shivers down my spine. But this belongs in a museum. Specifically, an Irish museum ..

So. What is it? It is a playbill from the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. Annual Oratorio season of 1824. Under the management of the Chevalier Bochsa. Bochsa, whatever else he might have been, was a fine musician and an enterprising entrepreneur ... just days previously he had given the first British performance of Stadler's Jerusalem Delivered, at Covent Garden's parallel series of sacred concerts, with the flower of British vocalists ... but this was something even more way out. An unpublished, unperformed oratorio by an unknown Irish, amateur composer which -- unbelievably -- used as its source Pope's The Messiah. Why? How?

Well, I have my theory. But it's only a theory. The young composer, arranger, 'author' of The Prophecy ... announced on the bill solely as 'an amateur' ... was a young Dubliner by the name of Joseph Augustine Wade. Esquire. I don't know if he really were an Esquire or not, but that's what he billed himself as. In the brief pieces devoted to him in various dictionaries, there seems to be a general consensus that he was born in 1796. He studied at Trinity College, medicine and then music, and took to writing poetry ... and along the way he met Sir John Stevenson, Mus Doc. (One day I must find out why this church singer was knighted; the Mus Doc was an 'honorary' degree). Wade supplied words for some of Stevenson's pieces, including the glee 'The Day-beam is over the sea' (1821), published as 'sung at the London, Bath and Dublin concerts', and ventured his own first songs and arrangements for the local Beefsteak Club, the Dublin concerts et al. He published a version of 'Robin Adair' decorated with embellishments said to be 'for Catalani'. None of this modest local work, however, prefigured an entire oratorio. I suspect the hand and/or influence of the knightly Mus Doc.

Wade's Prophecy made up only one-third of the programme and, as you can see, the singers for the whole concert were all billed in a lump, with no distinction. Thus, I don't know precisely who sang the work (apart from the Misses Paton and Venes) or for what voices it was written, for such reviews of the evening as I have found, so far, devote only a few and unspecific comments to what I imagine must have been the first Irish oratorio. However, those lines were not dismissive. If anything, they were favourable...

A 'selection from' the oratorio was given on 31 March at another of Bochsa's series, and even a third time on the penultimate night of the series, 7 April, along with an 'act' of Rossini.

Three performances. Apparently, of a decreasing part of Wade's opus. It would actually be given once more. The Dublin press reported that because of its 'brilliant success' the oratorio would be again sung in London. But the advertisement for the occasion (10 June 1825) sounds rather grumpy: 'the first and only time in this country as originally composed by ...' It sounds as if even the first performance had been of a cut-down version. Anyhow George Smart conducted again, Miss Paton and Braham and Phillips were there again, and that seems to have been the last time The Prophecy was ever given. Although, maybe it got a go in Ireland. Like Busby's work, it doesn't seem to have made it to the publishing desk.

However, we don't need to feel sad for Mr Wade. Although he would never again attempt anything on such a scale, and of such pretension, he was now established in the professional British music world as a Musician and a Composer and a Lyricist, and in the next twenty years songs would simply pour out of his plume on to the printing presses and music-stands of Britain.

I am no longer a Collector. Oh, I was, once ... rabidly. When younger. Music, theatre programmes, libretti, photographs, ephemera, recordings ... all the stuff that went into the making of my early multi-volumes books. But then I stopped. And what had been 'Kurt Gänzl's British Musical Theatre Collection' now nestles, courtesy of Dr James Ward, in the Harvard University Theatre Library. Some twenty years later, I wonder if the whole lot is catalogued!

Anyway, all that as a prelude to saying that the urge to acquire doesn't wholly go away. Every so often, in a shop or, these days, on e-bay and its ilk, I spy a little gem. Usually something ancient, from the narrowest part of my area of expertise ... and just about nobody else's! ... and of which, thus, nobody else knows the significance. And, thus, nobody cares much about. Excepting myself. Well, this week it happened. Here is the item. I know. Only I would get shivers down my spine. But this belongs in a museum. Specifically, an Irish museum ..

So. What is it? It is a playbill from the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. Annual Oratorio season of 1824. Under the management of the Chevalier Bochsa. Bochsa, whatever else he might have been, was a fine musician and an enterprising entrepreneur ... just days previously he had given the first British performance of Stadler's Jerusalem Delivered, at Covent Garden's parallel series of sacred concerts, with the flower of British vocalists ... but this was something even more way out. An unpublished, unperformed oratorio by an unknown Irish, amateur composer which -- unbelievably -- used as its source Pope's The Messiah. Why? How?

Well, I have my theory. But it's only a theory. The young composer, arranger, 'author' of The Prophecy ... announced on the bill solely as 'an amateur' ... was a young Dubliner by the name of Joseph Augustine Wade. Esquire. I don't know if he really were an Esquire or not, but that's what he billed himself as. In the brief pieces devoted to him in various dictionaries, there seems to be a general consensus that he was born in 1796. He studied at Trinity College, medicine and then music, and took to writing poetry ... and along the way he met Sir John Stevenson, Mus Doc. (One day I must find out why this church singer was knighted; the Mus Doc was an 'honorary' degree). Wade supplied words for some of Stevenson's pieces, including the glee 'The Day-beam is over the sea' (1821), published as 'sung at the London, Bath and Dublin concerts', and ventured his own first songs and arrangements for the local Beefsteak Club, the Dublin concerts et al. He published a version of 'Robin Adair' decorated with embellishments said to be 'for Catalani'. None of this modest local work, however, prefigured an entire oratorio. I suspect the hand and/or influence of the knightly Mus Doc.

So, come 24 March. The premiere of The Prophecy. Those with long enough memories, might have remembered the oratorio of the same title from the pen of Dr Thomas Busby, Mus Doc, organist of St Mary's, Newington Butts, 'a pupil of Battishill', also built on Pope's eclogue, which had been played at the Haymarket Theatre 29 March 1799, to a touch of amazement at an Englishman's temerity in treading where Handel had trod. It was given again in 1801, but an effort to publish it by subscription seems to have failed. And now it was to have a second, Irish metamorphosis.

Wade's Prophecy made up only one-third of the programme and, as you can see, the singers for the whole concert were all billed in a lump, with no distinction. Thus, I don't know precisely who sang the work (apart from the Misses Paton and Venes) or for what voices it was written, for such reviews of the evening as I have found, so far, devote only a few and unspecific comments to what I imagine must have been the first Irish oratorio. However, those lines were not dismissive. If anything, they were favourable...

A 'selection from' the oratorio was given on 31 March at another of Bochsa's series, and even a third time on the penultimate night of the series, 7 April, along with an 'act' of Rossini.

And the summary of the series quoth

The first real song hit was a number fabricated from a Mozart waltz and set to his words as 'Morning around us is beaming'. The song was taken up by Joanna Goodall, who featured it beside her Handel and Rossini arias at the Argyll Rooms, at the Manchester and Winchester concerts, at York, at Portsmouth, at the Abingdon Grand Music Festival, indeed, to many of the places where she went, over several years. 'Rapturously applauded and encored', 'a very pleasing composition', 'a beautiful serenade'.

He also made inroads into the theatre. Mr Webb introduced his 'Liberty, Gallantry, Whisky and Love' into John Bull and The Wags of Windsor, John Braham interpolated his 'A Woodland Life' into Weber's score for Der Freischütz, while Vestris gave his 'Tis the best of all delights' plugging Vauxhaull Gardens Sapio rendered his Scottish ballad 'Will you with me, my lov'd Mary', and in 1826 he came out with a complete original score and libretto for a full-scale comic opera.

The piece was entitled The Two Houses of Grenada and it had a creaky plot with reminiscences of a happy-ending Romeo and Juliet. Mr Wade was, it seemed, not talented as a dramatist.

But his songs for the show were something better than his dramaturgy. Miss Graddon scored with a ballad

The Two Houses of Grenada was played eleven times, and also apparently found the stage in Dublin where it was quickly slimmed into an afterpiece, but its favourite songs lingered on .. I see Kitty Stephens singing 'Love was once a Little Boy' at Braham's concert ...

Wade contributed songs to the theatre thereafter, including all the music for a well-liked little piece The Pupil of Da Vinci, at Braham's St James's Theatre, but again, he did not persist as a theatre composer. He wrote myriad published songs. but I see them published far more often than I see them performed in the better concerts.

Wade's biggest song success was 'Meet me by moonlight alone'. It has managed to survive two centuries to the Youtube age, in spite of being murtherously treated as a trad thwanging ballad by someone called the Carter Family. Here it is, with its virginity intact, sung as originally written, by Beret Arcaya, accompanied by guitar rather than piano or harp:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x9TO_YFFS2c

I don't know exactly when it was written and published, or where and when first performed. It wasn't, as far as I can see, plugged by such as Miss Goodall, Braham, Phillips or Sapio, although a copy in an Irish library is dubbed 'sung by madame Vestris' and dated 1827. My first sighting is in Leamington in late 1828, sung in a local concert by a Miss Sharpe, then -- already 'the favorite ballad' -- in Edinburgh by the better-known Miss Tunstall, sometime of Vauxhall. No mention of it being a 'new song', but I can't find Vestris either. In London, it was played at the Apollicon, and Mrs Waylett introduced it at the Tottenham Court Theatre, in what appears to have been a version of The Bride of Lammermoor entitled The Field of Forty Footsteps. Then Miss Stephens sang it a Drury Lane concert, Mrs Waylett in The Belle's Stratagem and at her Benefit, at Bath ... Miss Love came out with an answer 'Yes, I'll meet thee by moonlight alone' credited to Mr L Zerbini, it was arranged, rearranged, guitarred by Sola, often treated as 'trad' and with Wade's credit omitted ...

I have a long list of J A Wade songtitles, culled from advertisements and sheet-music, and from library catalogues. I have a very much smaller list of those reported in the press as having been sung in professional concerts, although a number of the music-sheets have 'sung by' with a favourite name attached, in the manner of the time. Mrs Waylett seems to have been a faithful purveyor of Augustine's songs -- I see she stuck one into the play The Yeoman's Daughter in 1834 -- but, it seems, his market was mostly the drawing room piano

I'm going to leave Mr Wade there. There's plenty more on him and his work to be found if anyone wants to look. I'll just leave him, here, with the two-page (yes, TWO PAGE) obituary printed on his death, before the age of fifty, in The Musical World. It is far from impeccable -- for example, The Prophecy is forgotten and misdated -- but it is the most substantial piece on Wade I have seen.

He also made inroads into the theatre. Mr Webb introduced his 'Liberty, Gallantry, Whisky and Love' into John Bull and The Wags of Windsor, John Braham interpolated his 'A Woodland Life' into Weber's score for Der Freischütz, while Vestris gave his 'Tis the best of all delights' plugging Vauxhaull Gardens Sapio rendered his Scottish ballad 'Will you with me, my lov'd Mary', and in 1826 he came out with a complete original score and libretto for a full-scale comic opera.

The piece was entitled The Two Houses of Grenada and it had a creaky plot with reminiscences of a happy-ending Romeo and Juliet. Mr Wade was, it seemed, not talented as a dramatist.

But his songs for the show were something better than his dramaturgy. Miss Graddon scored with a ballad

and what seems to be the whole score went into print ..

Braham's 'O, do you remember' and, especially, the duet 'I've wandered in dreams' outlasted the play by many years.

The Two Houses of Grenada was played eleven times, and also apparently found the stage in Dublin where it was quickly slimmed into an afterpiece, but its favourite songs lingered on .. I see Kitty Stephens singing 'Love was once a Little Boy' at Braham's concert ...

Wade contributed songs to the theatre thereafter, including all the music for a well-liked little piece The Pupil of Da Vinci, at Braham's St James's Theatre, but again, he did not persist as a theatre composer. He wrote myriad published songs. but I see them published far more often than I see them performed in the better concerts.

Wade's biggest song success was 'Meet me by moonlight alone'. It has managed to survive two centuries to the Youtube age, in spite of being murtherously treated as a trad thwanging ballad by someone called the Carter Family. Here it is, with its virginity intact, sung as originally written, by Beret Arcaya, accompanied by guitar rather than piano or harp:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x9TO_YFFS2c

I don't know exactly when it was written and published, or where and when first performed. It wasn't, as far as I can see, plugged by such as Miss Goodall, Braham, Phillips or Sapio, although a copy in an Irish library is dubbed 'sung by madame Vestris' and dated 1827. My first sighting is in Leamington in late 1828, sung in a local concert by a Miss Sharpe, then -- already 'the favorite ballad' -- in Edinburgh by the better-known Miss Tunstall, sometime of Vauxhall. No mention of it being a 'new song', but I can't find Vestris either. In London, it was played at the Apollicon, and Mrs Waylett introduced it at the Tottenham Court Theatre, in what appears to have been a version of The Bride of Lammermoor entitled The Field of Forty Footsteps. Then Miss Stephens sang it a Drury Lane concert, Mrs Waylett in The Belle's Stratagem and at her Benefit, at Bath ... Miss Love came out with an answer 'Yes, I'll meet thee by moonlight alone' credited to Mr L Zerbini, it was arranged, rearranged, guitarred by Sola, often treated as 'trad' and with Wade's credit omitted ...

I have a long list of J A Wade songtitles, culled from advertisements and sheet-music, and from library catalogues. I have a very much smaller list of those reported in the press as having been sung in professional concerts, although a number of the music-sheets have 'sung by' with a favourite name attached, in the manner of the time. Mrs Waylett seems to have been a faithful purveyor of Augustine's songs -- I see she stuck one into the play The Yeoman's Daughter in 1834 -- but, it seems, his market was mostly the drawing room piano

I'm going to leave Mr Wade there. There's plenty more on him and his work to be found if anyone wants to look. I'll just leave him, here, with the two-page (yes, TWO PAGE) obituary printed on his death, before the age of fifty, in The Musical World. It is far from impeccable -- for example, The Prophecy is forgotten and misdated -- but it is the most substantial piece on Wade I have seen.

Saturday, July 6, 2019

The story of an Investigative Theatrical Carpet

.

The theatrical 'puzzles' are starting to pile up on my desktop. So maybe it's time for me to have a crack and one or two. I've been 'in France' all weekend, translating a big bundle of 200 year-old French poetry, so why not start with my French folder ...

A splendid little group of 1860s performers fell into my net last week, and I was well on the way to winkling out the odd identity when 1830s poetry intervened ... so here's what I have uncovered, and what still remains to be uncovered ...

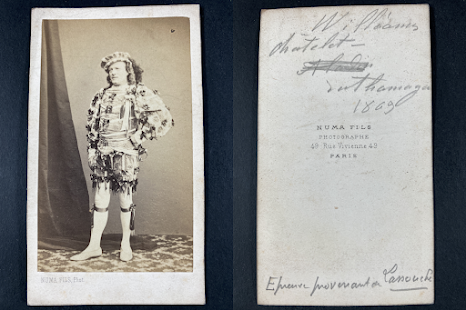

The key photo in the bundle was this one

Yes, well, it's a wizard. So we are immediately plunged into the glorious world of the classic French féerie spectaculars. Plenty of candidates, but one outstanding one. Rothomago. Rothomago, produced at the Cirque in 1862, and transferred to the Châtelet ... The titular Rothomago is a wizard ...

The rôle was created by the actor Lebel, and although it was later played by others, this is he. How do I know that? Because Lebel had the goodness to sign a copy to a friend, and that copy has survived to this day.

Now, pictures of the original Rothomago production can be found, but you've got to be wary. There is a splendid set of Nadar photos in the French National Library. But they are from the 1877 revival. In which Lebel's role was played by the decidedly more rolypoly Tissier.

The theatrical 'puzzles' are starting to pile up on my desktop. So maybe it's time for me to have a crack and one or two. I've been 'in France' all weekend, translating a big bundle of 200 year-old French poetry, so why not start with my French folder ...

A splendid little group of 1860s performers fell into my net last week, and I was well on the way to winkling out the odd identity when 1830s poetry intervened ... so here's what I have uncovered, and what still remains to be uncovered ...

The key photo in the bundle was this one

Yes, well, it's a wizard. So we are immediately plunged into the glorious world of the classic French féerie spectaculars. Plenty of candidates, but one outstanding one. Rothomago. Rothomago, produced at the Cirque in 1862, and transferred to the Châtelet ... The titular Rothomago is a wizard ...

The rôle was created by the actor Lebel, and although it was later played by others, this is he. How do I know that? Because Lebel had the goodness to sign a copy to a friend, and that copy has survived to this day.

|

| Tissier |

Now, pictures of the original Rothomago production can be found, but you've got to be wary. There is a splendid set of Nadar photos in the French National Library. But they are from the 1877 revival. In which Lebel's role was played by the decidedly more rolypoly Tissier.

But. I'm pretty sure that a couple of my other 'catches' are from the same production. And, certainly, this one: Lebel's inseparable double-act partner, the 'idoles du publique', William[s]. Yes, born in Paris of English parents: Charles Addison Williams (1815-1883).

Why? LOOK AT THAT CARPET! It is surely the same photo session. In fact numbers two and four are pretty surely the same lass. Are they ALL the same lass? Surely not, the legs on number three are much less healthy...

But which lass?

He played the Prince in the affair ...

Why? LOOK AT THAT CARPET! It is surely the same photo session. In fact numbers two and four are pretty surely the same lass. Are they ALL the same lass? Surely not, the legs on number three are much less healthy...

But which lass?

Well, the 'principal boy' was 'Mademoiselle Milla' (née Laure Dordet, d 1900), replacing the Cirque's Judith Ferreyra, who would later return to her role, but who was soon to be prey to the rotting disease that would put an end to her career the following year and, ultimately, kill her, just after her thirtieth year.

|

| Judith Ferreyra |

|

|

|

The ingénue was my favourite Ernestine Esclozas. She played a peasant girl, so it's hardly she. But what's this ...? SAME CARPET! I must check the ins and outs of the plot!

That's surely she. And nos 2 and 4 of the who? lot ..

But what is this other name, billed large alongside Mlle Milla. 'Maria Bellamy' (ossia Belamy)? To play the Princess. The daughter of La Fée Rageuse? Originally played by Coraly Geoffroy.

Well, I just happen to have a photo labelled 'Bellamy'. It's from the Châtelet's later production, Marengo.

Yes? Could be. But the lady in my photos doesn't look very Princesse-ly, does she? This would be more what I'd expect

Maria Bellamy ('très jolie, très fine, très mignonne') came to the Châtelet from the Gaîté and the Folies-Dramatiques (Comme on gâte sa vie, Le voyage à Vienne, Galopin in Les écoliers en vacances) and became a favourite soubrette on the new stage. After Rothomago, she appeared in La Prise de Pékin, as Mary the maid in Le Secret de Miss Aurore, and as the drummer boy in Marengo before her death, still in her twenties, 'from a cold bath' in August 1863.

There were plenty of other lassies in the cast, of course. Mlles Caroline and Anna and Mme Lacran in small parts, and then the ladies of the ballet who represented the hours of the Magic Clock which was central to the show's story. Mlles Victorine (l'heure du coucher), Clémence (l'heure de la prière), Lagrange (l'heure de minuit), Esther (l'heure du dîner), Elisa Bellamy (L'heure du bal), Agnès (l'heure de la liberté), Jenny Pazza (l'heure du travail), Caroline (l'heure du lever), Hélène (l'heure du déjeuner), Maria (l'heure du jeu), Bonnet (l'heure du plaisir), Octavie (l'Heure du berger), Gabrielle, Robert, ... and for the Lace Ballet, Mlles Henecart, Elisa Piron, Letourneur, Octavie Berger and Anna Buisseret, later Mlles Badernac, Laurençon, Petit ...

These were not all just dispensable chorines. I have before me a cast list for the Châtelet's 1866 end-of-year revue and, alongside Mlles Milla and Esclozas, the names of Elisa Bellamy and Mlle Esther still appear in the lists. Elisa apparently stayed at the theatre for ten years, according to Lyonnet ... who unfortunately equates her with Maria! Esther, well, she rather looks as she would have been worth a ten-year contract! Dinnertime, indeed!

Is that the famous carpet again?

Death was unkind to another star member of the cast of Rothomago, as well. Colbrun, the little comic actor who appeared in the principal male role of Blaisinet died, before the age of forty, in 1866.

So, it seems as if we have here photos of the cast of the musical féerie spectacular which opened the Théâtre du Châtelet in 1862 ...

Or some of them. I'm still not sure about the one with the less healthy legs. And I suppose I'd better go looking for that carpet ...

ARGH! THE CARPET ....!

For the sake of reference, the original Cirque cast of Rothomago was, in its principal cast, identical to that at the Châtelet, with the exception of the replacement of Judith Ferreyra (apparently a little lost in the large auditorium) and that of Mme Geoffroy by Maria Bellamy (previously Béllami). However, a number of the supporting ladies were seemingly recast. Voici the names of the original featured dancers from the Hours and the Lace Ballet:

Madame Coustou (Spanish lace), Mlles Anais Letourneur (English lace), Anna Buisseret (Dutch lace), Pety (Malines lace), Adèle Ferrus (Venetian lace), Guerboroglio (Parisian lace), Lagrange (l'heure de minuit), Jeanne Pazza (l'heure de travail), Mlle Clémence (l'heure de prière), Mlles Kelly (l'heure de l'ennui), Ricard (l'heure de la liberté), Maria (l'heure du jeu), Bonnet (l'heure du plaisir), Thérèse (l'heure du bal), Octavie (l'heure du berger), Caroline (l'heure du lever), Esther (l'heure du dîner), plus Mlles Chatenay, Marzetti, Juliette, Hélène, Wall, Robert, Lhéman etc.

|

| Anais Letourneur as English Lace, dances her 'gigue anglaise' |

The other supporting ladies were Mlle Marguerite, Désirée Fieux, Jenny Kid and Mlle Moreau. Plus sixty corps de ballet...

At the moment, most of these are just names to me, although the paper L'Orchestre describes some of the dancers. But I am looking.

Ah! Jenny Kid 'the Queen of the Théâtre Féerique' an open-air entertainment in the Champs Elysées ..

And here is the cast of Les Sept Châteux du diable at the Châtelet in 1864 - Elisa Bellamy, Lagrange, Ferrus, Letourneur, Buisseret, Berger, Genty all still there and featured .. behind the great Esclozas and Lise Tautin ...

Ah! Anna Buisseret. Her sister, also a dancer at the Châtelet, was involved in a nasty affair of anonymous letters in 1874, then mixed with the law again in 1876 when one ex-lover killed another in a duel. She was described in court as 'une très vulgaire pècheresse dont le corps de ballet d'un thèâtre des féeries utilisait très récemment les mérites choréographiques'. How nasty! She had been, for more than a decade, a 'bien gentille' slightly featured dancer at the Châtelet and the Gaîté! And sister Anna was, by this time, no less than star dancer at the Gaîté. Anyway, in the course of proceedings the sister admitted to 35 years of age and christian name of Adrienne. So, presumably she was the lady who danced as 'Mademoiselle Adrienne'. And I doubt that Buisseret was their real name anyhow: the choreographer who, around this time, worked as 'Buisseret' was actually Etienne Morlet. Anna was to remain a star dancer for a goodly number of years. Adrienne vanished, allegedly, to 'marry an English Lord'.

Adèle Ferrus, 'la grande coquette', who had been a baby ballerina alongside Anna Buisseret at the Brussels Théâtre de la Monnaie in the 1850s, was the wife of 'Valentin' (de Waerghenare), sometime sous-chef d'orchestre at the Châtelet. He died at the age of 35 in 1874. She seems to have had a sister too. Ferrus I and Ferrus II played Pride and Envy in the Châtelet's Les Sept Châteaux du diable in 1864. Maybe the Antonia Ferrus who sppeared in Brussels and Toulon?

Mlle Letourneur, 'la soubrette du Châtelet', 'admirablement sculptée dans ses petits proportions ... à la fois chaste et provocante', who seems to have been a superior dancer, went on to, amongst other, be première danseuse in the Châtelet's Le Naufrage de la Méduse (1864), Les Filbustiers de la Sonore (1864, with Buisseret, Vernet and Ferrus), in the Théâtre Déjazet's Cendrillon (1866) burlesque, La Poudre de Perlinpinpin (1869), later delivering a snake-dance at the Alcazar (1869), and continuing on into the 1870s when she turns up at the Folies-Bèrgere (1870) and in 1876 in America, dancing for the Kiralfys in Around the World in 80 Days. If she is the same 'Mlle Letourneur' who was dancing already at the Porte Saint-Martin in 1852, and a coryphée at the Opéra 1853-4 ... but, there, 'Letourneur' is a predestined name for a dancer, and there were, over the years, several! But wait! 1874 'Mlle Letourneur la coqueluche des titis, l'ange du paradis' quitte le Châtelet ...'. The 'darling of the Gods' ... it seems that it is indeed the same one. Anais Letourneur ...

|

| Anais Letourneur |

Madame Coustou is another who seems to have had a long active life: in 1853 she danced in Le Consulat et l'Empire, alongside Lebel, at the Ancien Cirque, where two years later she can be seen in Les Pilules du diable; in 1875, she is principal dancer at the Théâtre Historique.

Back to carpet hunting ...

Post scriptum. I am beginning to wonder if they produced that carpet by the kilometre. Also, in how many shows that little flyaway headdress was worn ... but surely I've seen that stripey costume before ... Voyage à la lune?

Lebel in La Poule aux oeufs d'or ...

|

| Rothomago '77 |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)