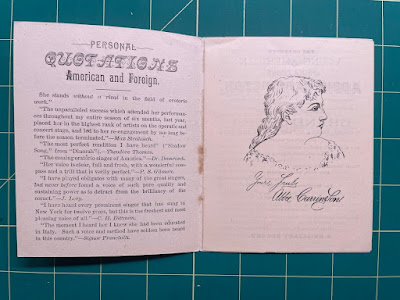

CARRINGTON, Abbie (née BEESON, Abbie) (b Fond du Lac, Wisconsin 13 June 1855; d 2041 Lyon Street, San Francisco 8 April 1925)

A volume entitled A woman of the century, by one Frances Willard, was put out in America, towards the end of the 19th century. It purported to contain biographical notes on 1,400 ‘important’ women of the American last hundred years. Abbie Carrington, for heaven’s sake, was one of those 1,400.

The case of Mrs Carrington is a fine example of that peculiarly American journalistic penchant (of that time, of course) to make ‘celebrated prima donna’s, with allegedly important European careers, out of ordinarily endowed hometown girls with a small or even no career. Abbie Carrington was one. She didn’t have ‘no’ career. She was employed on the stage for a few years as, mostly, a subsidiary lead soprano, by an impresario whom she ended up (apparently typically) suing … but, with a lot of help from her friends … well, here we go.

Abbie Beeson was born in Fond du Lac, a daughter of Edward Beeson, a printer, and his wife Susan Emily (née Bell), and she became Abbie Carrington by her marriage to Adalbert Rowland Carrington, at the age of seventeen (5 December 1872). Their daughter Mary was born, in Fond du Lac, the following year (b 17 March 1873; d 28 March 1962). Shortly after, they moved to Boston, where Abbie took singing lessons from local musician, J Harry Wheeler, before heading on to Italy, equipped with a new name ‘Iole Barbo’. She said, later, that she studied in Milan with Giuseppe Perini (perfectly possible) and made her debut in La Traviata in that city, and Ms Willard follows up with a perfectly reasonable – but wholly undocumented -- series of other engagements at Cervia (November 1878), Ravenna, Turin, Brescia and Venice. No theatres or artists or impresarii named anywhere, and try as I may, I can’t find a trace of any of this, even in the extremely voluble Italian musical press, which reported operatic performances in the tiniest of towns. No announcements. No reviews. I can find only ‘reports to home’, to a gullible hometown newspaper (editor: Mr Beeson?), which claim that she sang Marguerite, Violetta, Lucia, Elvira, Gilda … and Arline in The Bohemian Girl! At Ravenna? As for Traviata in Milan, well, at that period I can see a bundle of other striving, American girls giving their Violettas in Europe -- one of them was the young Albani, another Minnie Hauk, then there was ‘Bianca Lablanche’, Avonia Bonney, ‘Caterina Marco’, ‘Giglio Nordica’, ‘Laura Bellini’ … but I see no Barbo. And Traviata was indeed played in Milan at this time: at the Dal Verme by Flaminia Munari, Carolina di Monale, Rosina Isidor and Giuseppina de Senesplada, at La Scala by Marie Heilbronn, Mme Léon Duval and Adelina Patti… but I see no Barbo.

Anyway, in the US press, copied eagerly from one paper to another, this all developed into ‘the celebrated prima donna … sung in all the main cities of Italy …’ and so forth. I am, frankly, severely doubtful of the veracity of the whole lot. I can find the other girls, why not – even once – Signora Barbo? Although, I must say, performances at Cervia would escape all but the most minute operatic reporter. Not so, Milan, Turin and Ravenna.

Whang! Finally! I got one! Jolè Babó as Gilda! Guess where? Teatro Communale, Cervia, November 1878. With Dante del Papa and Francesco Tirini, Well, if one is true .. Yes! Teatro Mariani, Ravenna, November 1879, with the same team … Eh? Well, that means that Ravenna wasn’t young del Papa’s debut, as biographized, and that Jolè was on both sides of the Atlantic at the same time. But, at least, if not in ‘the greatest theatres in Europe’ her little engagements weren’t fictional! And her young tenor would go on to a fine career.

She was said to be back in Boston by August 1879 and, apparently, performed there before making her New York debut under Theodore Thomas in October at the Philharmonic Concerts. ‘Her success was fair. In the first selection, ‘Hear ye, Israel,’ she was prevented by nervousness from doing herself justice. She sang the ‘Shadow Song’ from Dinorah, and as an encore the Bolero from the Sicilian Vespers’ …’. Thomas was quoted as saying he’d never heard the Shadow Song sung like it. I wonder if his tongue was in his cheek.

She sang at Gilmore’s concerts at the Grand Opera House (‘Let the Bright Seraphim’) and, in spite of typical newspaper rumours that she would join Mapleson for opera in Boston, continued on to a Stabat Mater in Baltimore and Messiah in Washington. She sang at Koster & Bial’s for Levy’s Benefit and then set out on a concert tour with the Boston Mendelssohn Quintette Club. Again she flourished her Shadow Song and won some fans (‘The Club never played better, and Miss Carrington captivated the audience with her artistic efforts. The freshness, purity, and skilful management of the voice, clear and distinct enunciation, together with the unaffected naturalness of the singer …’) and some reactions a little more distant (‘the substantial prima donna … cultivated and pleasant but not phenomenal’). ‘Miss Abbie Carrington has proved an excellent vocalist for the club during their tour, and won favor throughout the western circuit’. Well, not quite throughout. At St Paul she didn’t turn up, and after waiting an hour for her, the Quartette had to borrow a local lassie. Someone said she was down in Chicago singing The Creation.

Finally, came that operatic engagement. Clarence Hess, one of the era’s best touring opera managers, hired Miss Carrington (sic) for a tour. Germany’s Ostava Torriani and France’s Marie Roze, first-class leading ladies, both, topped the soprano bills, with the Misses Schirmer and Carrington of Boston behind. But Miss Carrington didn’t want to be behind. She sulked her way through Fra Diavolo while Ostava triumphed in Aida and Faust, and while Roze gave her Carmen, with Schirmer as Micaela, and she wasn’t even contented when she was handed some The Bohemian Girl and Mefistofele performances. So she stirred. She pouted ‘favouritism’ (Torriani, she alleged, was sharing a bed with co-manager Strakosch), told the press that she was going to take over the management of the company to re-organise things, and when that pronouncement didn’t have any effect, she sat down in Cleveland and would go no further.

And who would believe it? When Adelaide Randall went sick, the next season, they hired her back as a replacement, and Strakosch hired her again, with Maria Leslino and Blanche Roosevelt, for the 1881-2 season. Abbie’s version was that she and Etelka Gerster would sing the high and light repertoire alternately. Of course, they didn’t. But, this time, she didn’t sit down in Cleveland, she stayed and sang with the company at Booth’s Theatre in February 1882, before touring onwards. I catch up with them in Boston in May. Gerster now had Minnie Hauk and Clara Louise Kellogg as co-donnas. So Abbie pouted some more. She’d been promised Pamina and Filina, she told the press, and she’d only got Micaela, and it wasn’t her fault she’d got sick the night Carmen was played. And, anyway, she wasn’t staying, she was going to Europe. Seemingly, she didn’t. She put out the Abbie Carrington Concert Company touring from Walukesha to Green Lake, and with her singing and her husband’s drumming (of which more anon) featured.

But who would credit it, at the end of 1882, Hess hired her yet again. But this time in more modest company. No Torriani, Roze or Gerster. She was assoluta. Emma Elsner was the second prima donna, with Rose Leighton and Lizzie St Quinten from British musical comedy ranks. There was a reason, though. There was no Aida, no Carmen. The repertoire included Maritana, Fra Diavolo, The Bohemian Girl, Martha, Faust … HMS Pinafore, Iolanthe, Les Cloches de Corneville, La Mascotte, Fatinitza … Chicago wasn’t impressed by the latest Hess company: ‘He has one good soprano in Emma Elsner, and a fair one in Abbie Carrington, but the latter is too fat for most roles. It is pitiable to see her waddling, as Arline, through The Bohemian Girl.’

So Hess took his company to Mexico. The first tenor was George Appleby, a former bit part player from Britain’s Emily Soldene company. Abbie must have done something right, even if only journalistically, because the worldwide press soon reported that she’d been offered marriage, money et al down Monterey way. If it were true, she might have helped Hess. The Mexican season was a financial disaster.

Now here we meet a decidedly problematic bit. The papers (briefly) and the imaginative Ms Willard (doggedly) claimed that Abbie went, on two separate occasions, to England, once to sing at the Covent Garden Italian Opera and, again, even more improbably, at Her Majesty’s Theatre. I’m not sure where these ‘visits’ are supposed to fit in, but unless she had yet another pseudonym up her capacious sleeve, I will state categorically: she simply did not! I have been able to find only one possible instance of the lady singing in England. ‘Madame Carrington’, with an amateur male quartet, at the Colston Hall, Bristol on 24 November 1886.

Mind you, perhaps she is the Mdlle Jole Grando who can be seen singing with prima donna Fanny Rubini-Scalisi in Nice in early 1885. Aida? The off-stage Priestess, maybe?

But, back home, she did again get her own company. Variously under the cognomen of the Abbie Carrington Concert Co or the Abbie Carrington Grand Opera Co (manager: Mr Carrington). And she persisted. In 1891, I see her giving The Rose of Castile in Montana with a total personnel of seven (‘the greatest…’), a piano accompaniment, no scenery and of course, no chorus.

At some stage, as what passed for a career foundered, so did a marriage. I thought Adalbert must have died, but he didn’t. Which makes Abbie’s 1899 wedding to British pianist Emlyn Lewys (as Abbie Iola Beeson Carrington) reasonably bigamous.

Mr and Mrs Lewys settled in San Francisco. The ‘celebrated prima donna’ who’d ‘sung at the best opera houses in Europe and England’ (pardi!) and, more factually, who’d quarreled with, or sued, some of the best touring opera managers in America, mostly for not giving her starry parts, taught music. And gave her Shadow Song occasionally …

Exit ‘Iole Barbo’.

‘Mme Abbie Carrington (Mrs Emlyn Lewys) Prima Donna Soprano Voice Posing and COMPLETE OPERATIC TRAINING Mr Emlyn Lewys, BA Pianist and Teacher of Scientific Technic and Interpretation. Studio: 1712 Bush St., near Gough.’

Mr Carrington, however, seems to have had an hour of dubious glory in latter days. He stayed in Chicago, while his wife ‘remarried’. And, in 1890, a census-taker made a discovery. Adalbert was the famous ‘Drummer Boy of Shiloh’, the 11 year-old who had shot a General … or whatever. The news went viral (he had actually joined up, in 1861, as a ‘musician’) and it seems as if he may have, latterly, taken his drumming act on the music halls. Of course, there were a few other drummer boys who claimed to be the Shiloh boy…

I should add, in conclusion, that daughter Mary Carrington attempted a career as a singer …

End of story. And that’s one of the 1,400 most notable women of the American 19th century? I think not. But myths persist: now, Abbie Carrington has, for heaven’s sake, an entry on Wikipedia! With all the likely lies and phony claims intact! How to fake history, indeed. But I suppose it helps when Papa has a newspaper …

Found years later ...

No comments:

Post a Comment