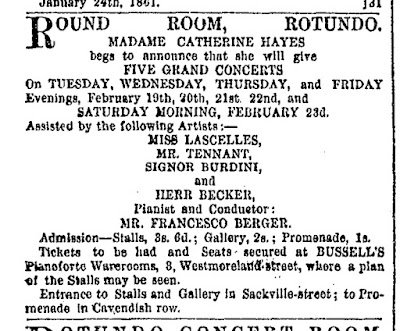

I had never before seen a photo of that fine Victorian contralto known as Annie Lascelles, so when this turned up yesterday, I thought 'here is a chance to post my rather detailed ten-year-old article on the lady and her career ...'

LASCELLES, Annie [COBB, Sarah Ann] (b Newark upon Trent, Notts x 7 December 1826; d 6 York Street, Portman Square, London 15 May 1907)

Many Victorian vocalists hid – with more or less purposefulness and more or less efficacity – their real identity and background behind not always foreign names, behind fanciful ‘histories’ and fabricated ‘biographies’. And many Victorians, vocalists or not, dissembled with regard to their personal truths, of one kind or another -- with more or less efficacity and more or less consistency -- when it came to official documents. From birth, death and marriage registrations to that veritable playground for fibbers, the census lists. A century and more down the line, it can be difficult – sometimes more, sometimes less – to strip aside all their pretences and pretensions, and winnow the truth from the lies.

The statuesque contralto Miss Annie Lascelles, subsequently Madame Berger-Lascelles, was one whose truths I thought that I would probably not uncover, for she and her husband had strewn their imaginative re-makings of her background about pretty freely and decidedly confusingly. In the 1881 census, for example, she was Annie Berger, married, aged forty, born Leicester, and her sister, Mary Lascelles was right there alongside her to show that she was indeed née Lascelles. It looked as if it were going to be straightforward. But it wasn’t. For as you can see above, the lady was not Annie, nor Lascelles, she was fifty-five and she was born not in Leicestershire but in Nottinghamshire. So, I started looking in all the wrong places.

Then I came upon a concert review from Stamford which said that the young contralto was ‘well known in this locality, she having resided with her parents for some time in Grantham’. Resided. But not born. Next came the 1901 census, in which she admitted shrinkingly to 59, and told us that she was born in Newark upon Trent. But since that same document said that her husband Francesco Berger (‘aged 63’) had been born in Austria, that entry seemed a bit dubious. For Francis (sic) Berger, the son of an elder Francis Berger and his wife Mary Ann Jane ka Nannette, was some seven years younger than his wife (b 10 January 1834), not four years older as he said, and was pure London-born and bred.

|

| 1834 |

But I got there. And, as one finds so often, the aristocratic nom de théâtre – for by now it had become clear that in spite of Mary’s corroboration of the ‘Lascelles’, it was indeed a pseudonym – hid a decidedly unaristocratic background.

Sarah Cobb was indeed born in Newark upon Trent, Nottinghamshire, not in 1841 but in 1826, the first daughter of George Cobb, an innkeeper from Lincoln, and his wife Ann née Hutchinson who had been, it seems, rather necessarily, married in Newark on 19 July 1826. They can be seen in the 1841 census living in Angel Row, Nottingham – George and wife Ann, with Sarah aged 14, Mary aged 10, Thomas aged 5, Charles aged 4 months, and Ann’s mother, plus what look like three young inn servants. For father runs the historic Bell Inn, Market Place, Nottingham. All the Cobbs, so the document assures us, except papa, were born in Nottinghamshire. They weren’t, of course.

My first sighting of the future Miss Annie Lascelles on the concert platform is in 1849 (12 January), when she was some 22 years of age. But she is not yet metamorphosed into Annie Lascelles, she is still ‘Miss Cobb of Grantham’. The venue was the Town Hall, Grantham (‘a talented resident musician’), and the supporting cast, from Leicester, included flautist Nicholson, who played the obbligato to her ‘Nel lasciar’, and tenor Oldershaw, and after the ‘The Swiss Girl’ and ‘The Syren and the Friar’ the local paper affirmed that ‘she possesses every requisite for a first-class singer’.

I see her again – always with Nicholson -- at Loughborough (‘her second appearance’), then at Newark (‘Lo, here the gentle lark’, ‘The Swiss Girl’) and 15 January 1850 ‘her first appearance since her return from London, where she has been studying [for four months] under the celebrated Manuel Garcia’, back in Grantham, singing her Lark again.

On 22 April she appeared at New Hall in Wellington Street, Leicester, on the occasion the last of the season’s local Monthly concerts. Miss Cobb shared the bill with two well-liked and very much more experienced vocalists, Annie Romer and Frank Bodda, and she won herself an encore for a Henry Farmer song ‘I’ll follow thee’. The song did not impress the often sour critic of musically-faction-ridden Leicester who deemed it ‘chiefly remarkable for the absurd number of repetitions of the words forming its title …these however were nearly the only words that could be heard for the lady’s articulation was so indistinct’. In fact, this critic didn’t care for Miss Romer, currently the rising darling of the Liverpool operatic stage, and he didn’t care for Miss Cobb either. ‘Miss Cobb exhibited a command over a contralto and soprano range of voice, but the lower notes were forced and coarse, the middle ones weak and indistinct, and the upper deficient in power and brilliancy, while at the same time her intonation was imperfect and she indulged too much in startling contrasts of forte and pianissimo, though she displayed considerable execution and warmth of feeling, sufficient to ensure her a reasonable share of popularity and applause’.

‘Miss Cobb of Grantham’, however, turned up at Stamford with Thaddeus Wells, in Leicester again, in the Christmas Choral Concert at the Mechanics' Institute (‘The Keepsake’, ‘Home Sweet Home’) and, in February of 1851, Miss Cobb’s Annual Concert was given in her home town under the patronage of the Duke of Rutland and half a dozen other aristocrats. Frank Bodda was the guest singer, there was a local glee team trained by Miss Cobb, and there were also lots of encores, in spite of the piano being a semitone flat, which rather warred with the violin obbligato to ‘Home of Love’ and Henry Nicholson’s flute accompaniment to ‘The Mocking Bird’.

In April, Miss Cobb appeared at Mr Cooke’s Nottingham concert, but sometime between then and October, Miss Cobb decided it was time to upmarket her image, and by the time she appeared at Barnet on 8 October 1851, alongside Sophia Messent and a Mr W H Grattan, at Frank Bodda’s Evening Concert, she was ‘Miss Lascelles’. She was also ‘a pupil of Frank Bodda’ and described as making ‘her first appearance in public’. ‘As a debutante she was decidedly successful. Her voice is a mezzo-soprano of nice quality, the lower notes being rich and resonant.’ 13 November, at Saffron Walden, ‘Miss Lascelles’ shared a bill with Miss Eyles and Donald King.

My first London concert-room sighting of ‘Anne (sic) Lascelles’ is at Willis’s Rooms, shortly after, in a concert given by one Miss Wheatley (piano), where she shared a bill with Miss Poole, and two other rising vocalists in Mary Ransford and Allan Irving, and subsequently at Exeter Hall, taking part in a ‘Grand Musical Festival’ on 25 February 1852 alongside the Sims Reeveses, Henry and Miss Phillips (‘daughter of’, poor thing), Sophia Messent, Rebecca Isaacs, Mary Ransford, Grace Alleyne, Miss Eyles, Miss Binckes, Evelina Garcia, Frank Bodda, Ferdie Jonghmanns, T A Wallworth, Mr Swift and Henri Drayton. I can’t find a review, but she must have done well for she swiftly became a fixture on the London concert scene, starting her ubiquitousness at Joseph Stammers’s London Wednesday Concerts with the elder Braham as bill-topper (17 & 31 March), the Exeter Hall Grand National Concerts (29 March) and the City Wednesday Concerts at Crosby Hall (31 March). Then, in April, it was that Stamford concert where she sang ‘Nobil signor’, ‘My native streams’, ‘I love, but I must not say who’, was noted as a ‘local’ and billed as ‘of the Exeter Hall concerts’. The reinvented ‘Annie Lascelles’ was on her way.

Before the year was out, she’d been heard in a good number of concerts – from the Highbury Tavern (Langton Williams’s ‘You’ll soon forget Kathleen’) to the soirées of Sophia Messent (‘a youthful vocalist ... sweet mezzo soprano voice ... taste and expression, a prepossessing manner and appearance’), delivering her ‘Nobil signor’ three time a week at various professors’ evenings, at the Hanover Square Rooms and Exeter Hall or the Eyre Arms, Kennington, and on 9 November she sang the contralto music in the Messiah at the Weslyan Chapel, Hackney Road, alongside Georgina Stabbach, Tedder and Lawler. ‘A pure contralto’ reported the press and, already, ‘one of our best contraltos’ singing George Linley’s ‘Ida’ at Hackney. One of our best contraltos – and a real one -- she might indeed have been, but it was to take several seasons for Annie to confirm herself as a member of the group de almost tête of contralto vocalists, following behind the acknowledged leader in the genre, Charlotte Sainton-Dolby, in the lists of the favourite and the fashionable.

During that period she performed in a number of other Messiahs – one at the Royal British Institute (12 October 1853 with Sophia Messent, Benson and Lawler) and, more adventurously, one with the Harmonic Union (28 November 1853) where Pauline Viardot Garcia, scheduled to sing most of the soprano and contralto music, scratched, and the Misses Stabbach and Lascelles who were there to sing the bits Mme Viardot didn’t want, ended up doing the whole thing. In 1855 (7 March), she performed the Stabat Mater with the Sims Reeveses and Weiss for the same Society. Mostly, however, Annie Lascelles appeared in concert, in London and in the provinces, at Crosby Hall, the Réunion des Arts, at Willis’s Rooms, but most often at Exeter Hall and the Hanover Square Rooms.

In her concert appearances, she covered most of the contralto repertoire, from the Italian operatic aria to the folk song, but although I have spotted her giving ‘Nobil signor’ at the Exeter Hall Wednesday concerts, ‘Ah quel giorno’ (Semiramide) at George Case’s annual and ‘La ci darem’ in tandem with Frank Bodda at his concert, it was in English and concert music that her ‘rich contralto’ was most frequently and ‘universally admired’, music ranging from contralto classics such as Benedict’s ‘By the sad sea waves’ to fellow vocalist Maria Merest’s ‘I’m the genius of the spring’ and ‘I saw thee weep’, G A Osborne’s scena ‘The Lord of the Castle’, and modern ballads of the type of ‘I loved 'ere yet I saw her’ by Virginia Gabriel (‘sung with much feeling’), ‘The birdies’ song’ by Mrs Henry Ames and the Hon Mrs Norton, Glover’s ‘Come off the moors’, Mrs Grooms’ ‘Over the sea’ or, her standby of the season of 1856, Langton Williams’s ‘Adele, or I miss thy kind and gentle voice’, to ‘Kathleen Mavourneen’. ‘Her fine voice requires only cultivation and flexibility to make her a very effective vocalist’, quoth The Era critic in late 1853.

The season of 1856 seems to have been a particularly busy one for the young contralto on the London concert scene. She appeared at the St James’s Theatre in the concerts topbilling ‘the blindborn Sardinian Minstrel’ Picco with his virtuoso pennywhistle, in the ambitious programmes at the so-called Royal Panopticon – an ill-fated attempt to deal up science and culture in the vastness of what would later be the Alhambra, where she sang alongside the performances of the luminous and chromatic fountain and a lecture on the Rotatory Motion of the Moon – and in a whole host of personal concerts from Exeter Hall and St James’s Hall to the Manor Rooms, Hackney and the mansions of the aristocratic and the wealthy. One notable engagement was for the concert given at Willis’s Rooms by Giovanni and Giacinta Puzzi, an annual affair which still rated quite high on the list, perhaps even at the very top, of the contenders for the title of most fashionable do of the season. The wheeler-dealing Puzzis were deeply ‘in’ with the powers that be and the powers that sang at the Italian opera, and many of the biggest stars of that institution would inevitably be on the bill at ‘Papa’ and ‘Mama’ Puzzi’s Benefit. In 1856, they did not even bother to advertise the stars names, they simply billed ‘the entire company (excepting Alboni) from Her Majesty’s Opera House’ plus Viardot, Pischek … English names were rare. This year, there were only Clara Novello and Giubilei and – for the third year in succession – Miss Annie Lascelles. Elsewhere, she sang on the bills presented by David Miranda, George Case and William Youens, Langton Williams, Frank Bodda, Ada Thomson, Augusta Manning, Annie de Lara, Giulio Regondi, Bernhard Molique, the RAM’s John Thomas, harpist Boleyne Reeves, for the Warwick Street Schools and Queen Charlotte’s Hospital and doubtless many more, as well as at dates the length of Britain, from the Mechanics’ Institute, Plymouth to Bradford’s St George’s Hall in a date with the local Choral Union.

1857 seems to have been, on the face of it, a little less hectic, but the concerts of the year included this time one of her own. Miss Lascelles’s first grand matinee musicale took place on 7 July 1857 at Willis’s Rooms with a bill topped by Anna Caradori and Helen Lemmens-Sherrington, plus Mme Comte Borchardt, the McAlpine sisters, ‘Jullien’s new tenor’ Henry Croft from Liverpool, Jules Lefort, Signor Monari and Herr Colbrun ‘from the Royal Opera, Dresden’ plus an unannounced Miss Alice Ronayne who may have been one of Annie’s pupils (for already she was advertising 28 York Place, Portman Square, engagements and pupils..’). The Era reported ‘Her own singing of course came in for the lion’s share of the applause, and applause it deserved, for we need not observe that she possesses one of the finest contralto voices in England, while her vocalisation betrays intelligent teaching and great natural taste. The selection she made embraced several styles from the Italian scena down to an English ballad.’

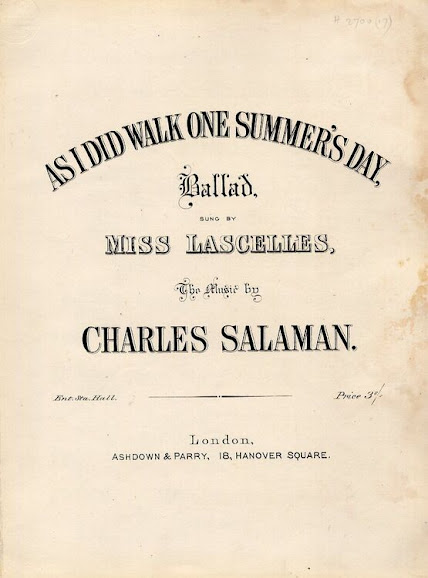

The English ballad may very well have been ‘The Fairy Dream’, which had been published earlier in the year by Messrs Duff and Hodgson with Annie’s portrait in colour emblazoned across its front, the publishers obviously hoping she would score the same success as she had with the previous year’s ‘Adele’. Alas, the piece – the work of one Miss Charlotte Rowe, until recently of the RAM --, vanished without trace. The next season, Langton Williams came up with a veritable carbon copy of his earlier hit in ‘Clarine, or 'tis a form that reminds me of thee’ and success was again at the rendezvous.

On 25 January 1858, Adelaide Maria Louisa, the Princess Royal, eldest daughter of Queen Victoria, married Prince Friedrich Wilhelm, brother of the King of Prussia, and in the evening, when the bridal couple had departed for Windsor, the Queen held a state concert in the new ball and concert room at Buckingham Palace. An orchestra of 200, a chorus of 100, and the soloists for the occasion were the Misses Pyne and Novello (sop), Lascelles (con), Giuglini and Reeves (tenor) and Weiss (bass). Annie sang the contralto line of the quartet ‘Placido e il mare’ (Idomeneo) and joined Novello, Reeves and Weiss in the performance of Michael Costa’s occasional serenata The Dream.

The year brought several other prestigious engagements to mix with the run of regular concerts. On 10 May Annie and Clara Novello were the featured vocalists at the Philharmonic Society’s third concert, Annie giving ‘Paga fui’, the contralto aria from Winter’s Il ratto di Proserpina, as her number, and in August she made her first appearance as a provincial music festival, in the occurrence the Festival of the Three Choirs, which this year was being held at Hereford. Clara Novello, Georgina Weiss, Louisa Vinning, Pauline Viardot Garcia, Mrs Clare Hepworth and Annie Lascelles were the principal ladies engaged, and as the only full-scale contralto on the bill, Annie found herself with a heavy workload, starting on Day one with the Dettingen te deum (‘acquitted herself very satisfactorily’) and the ‘Jubilate’ of conductor Townshend Smith in the morning and a duet with Mrs Weiss in a Clemenza di Tito selection plus the rather out-of-place ‘Adele’ in the evening; on day two, she shared the contralto part of Elijah with Mme Viardot, joined Reeves and Mme Weiss in Henry Leslie’s trio ‘O Memory’ and took part in the glee ‘The Fisherman’s Good Night’, and on day three joined Mesdames Weiss and Hepworth in Athalie, and took part in a selection from the Stabat Mater and another from Semiramide. (‘Bella imago’ with Weiss, ‘L’usato ardir’). On the final day The Messiah was given by almost all the soloists with, as in most of the items, Mme Viardot culling most of the contralto gems. Annie also took part in a Rossini quartet and gave the old ballad ‘Huntingtower’. Her reviews were not impeccable: ‘Her voice is a pure contralto, but there is a peculiarity about it which is not pleasing. She appears to sing from the throat which gave cause to a local critic for describing it as a ‘muffled contralto’.

At Christmastime, however, when Annie repeated her trip to Manchester for the seasonal Messiah there, she got to sing the whole of the contralto music, in a team with Susan Sunderland, George Perren and Belletti.

As had 1858, 1859 began with a royal event when Annie was engaged to sing the role of the Queen in The May Queen with Louisa Pyne, and original cast members Sims Reeves and Weiss, on New Year’s Day at Windsor Castle, and it continued on at a very vigorous pace. She took part in the very first edition of the Monday pops (Macfarren’s ‘Lily Lye’ ‘displays in an extraordinary degree the superb contralto points of which this lady’s voice is capable’), visited Manchester for yet another Messiah, repeated The May Queen with the Vocal Association, and appeared in concert for Howard Glover (‘Lily Lye’ Mercadante’s ‘A te riede’) the Royal Society of Musicians, Brinley Richards, Drew Dean, Langton Williams (‘Clarine’), Annie Elliott’s with her newest ‘expressly for’ song Charles Glover’s ‘For thy gentle voice to cheer me’ and, in April, visited Edinburgh to take part in the Handel Centenary Festival (Judas Maccabaeus, Messiah, Samson &c) with Mrs Sunderland, Wilbye Cooper, George Perren and Weiss. In May she shared the Messiah music with Charlotte Dolby at the Royal Society of Musicians, and repeated her entrepreneurial act of the previous year with a concert – an evening one this time, and at the Hanover Square Rooms (19 May). Helen Lemmens-Sherrington, Mary Ransford, Marian Enderssohn, Depret, Wilbye Cooper, Patey and Santley supported her, and Mr Francesco Berger conducted. At the end of the month (30 May) she again appeared with the Philharmonic Society, joining Novello, Reeves and Weiss (all originals) in a repeat of The May Queen and delivering Cherubini’s ‘O salutaris hostia’ in such a fashion as to win a curiously double-edged review from The Times: ‘an opportunity of showing that she possessed one of the most rich and beautiful contralto voices in existence – a voice that, properly trained and cultivated, might prove a fortune to its owner’.

The concerts succeeded one another through the height of the season (Paque, Mrs Anderson, yet another Madame Puzzi, Emanuele Biletta, more Howard Glover and more John Thomas etc) and at the end, Annie returned for a re-engagement at the Festival of Three Choirs, this time in Gloucester, repeating the Dettingen Te Deum, and in spite of the fact that original cast Charlotte Dolby was there, The May Queen, taking second contralto to Dolby in Elijah (‘Miss Lascelles made a strong impression in the air ‘Woe unto them’’) and the Messiah (‘O thou that tellest’), and contributing to the concerts headed by Titiens and Giuglini (Hatton’s ‘The Enchantress’, ‘La Carita’ &c).

Through 1860 and the early part of 1861, Annie Lascelles ‘whose contralto voice is so much and justly admired’ was regularly on show on London’s concert platforms, equipped with a good supply of new and newish English songs – Francesco Berger’s ‘Still waters run deepest’ and ‘There’s rest for thee in heaven’, Langton Williams’s ‘Absence or return’, Balfe’s ‘The Reaper and the flower’, Benedict’s ‘The Maiden and the river’, Henry Smart’s ‘Come back to me’, Howard Glover’s setting of Shelley’s ‘Swifter far than summer flight’. There was still place for classic pieces – at the Quintet Union’s concerts she gave Mozart’s ‘Non più di fiori’ and Mercadante’s ‘Il Sogno’, at Mrs Anderson’s fashionable concert she joined Mme Rieder, Augusta Thomson, Belart and Gassier in a new Pinsuti ensemble ‘Aux bords de la durance’, a trio from Le Pré aux clercs and the Rossini ‘La Carita’, at Howard Glover’s concerts she gave a Meyerbeer piece, ‘When maidens in Springtime’, and at Prince Galitzin’s concert she performed his Chanson Bohémienne and a selection from Glinka’s A Life for the Tsar – and for the occasional Messiah, and on 12 July 1860 she put forth her own latest concert, at Collards Rooms, with the usual fine bill: Catherine Hayes, the Weisses, Tennant, Oliva, Patey.

In February and March of 1861, Annie went out on a concert tour of Ireland and Scotland with the Irish prima donna Catherine Hayes, her compatriot Tennant, and Burdini, violinist Becker and with Berger as pianist. Scotland gave her credit for ‘great beauty of voice and excellent taste’. And then it was into the season – the Monday Pops, the Vocal Association (Goatherd’s song Dinorah), the Philharmonic Society (‘Non più di fiori, Cosi fan tutte trio with Parepa, Belletti), the Royal Society of Musicians Messiah, Mrs Anderson’s concert, the Grand Fête at the Surrey Gardens, the Crystal Palace, and the usual run of personal concerts including one mounted by Berger (30 May, St James’s Hall) in which the feature was a large selection from Don Giovanni . Annie sang Elvira to the Anna of Augusta Thomson, the Zerlina of Louisa Vinning, the Don of Santley and the Ottavio of Reeves. And another visit to Buckingham Palace for a state concert (28 June 1861) with Titiens, Patti, Gardoni, Giuglini, Santley and J G Patey. Her ballad of the season was once again by Langton Williams: ‘The Voices of the Past’.

‘The Voices of the Past’ was successful enough to be used again in the following seasons, but Annie brought out several other good new pieces in 1862 – Virginia Gabriel’s ‘Effie’, Berger’s ‘The Night Bird’ and Macfarren’s ‘Lily Lye’ all got repeated performances, in the course of the long list of concert dates she fulfilled. She made a number of appearances at the Monday pops (‘Che faro’, Meyerbeer’s ‘Les Souvenirs’, The Savoyard’s Song, ‘Paga fui’, ‘In questa tomba’, duets ‘Puro ciel’, ‘When the summer wind is blowing’ with Ann Banks &c), sang her regular engagement with the Philharmonic Society, alongside Mlle Guerrabella (‘Che faro’, duet ‘Vaghi colli’), gave ‘The Ash Grove’ (in English, alongside Edith Wynne and Mr Lewis in Welsh) on a couple of Welsh occasions, and Bellini’s ‘Se Romeo’ (I Capuleti) on non-Welsh ones, took part in various Messiahs, introduced Berger’s ‘Peace and Love‘ duet in tandem with Eliza Hughes and the Hon Alfred Stoughton’s ‘The Spell of thy beauty’, sang at the Jenny Lind concert (9 July) at St James’ Hall and promoted her annual own concert, this time in the form of a matinee at the home of the Marchioness of Downshire (23 May). The members of the Catherine Hayes concert party made up the bulk of the bill, but alas, without Miss Hayes, who had died shortly before. Mlle Guerrabella and Louisa Vinning filled the gap. I see that Annie sang ‘Di tanti palpiti’, ‘Effie’, ‘Les Souvenirs’, the Gazza ladra duet and ‘a new song’, ‘The Night Bird’ by Francesco Berger. The two ladies joined Tennant and Burdini in a rendition of the Polish National hymn to close the first part.

Annie’s career as a concert vocalist was a full and well favoured one, but her teaching practice was also well under way … ‘35 York Street, Portman Square, amateur reunions for the practice of vocal part singing, conductor Mr Francesco Berger..’ Mr ‘Francesco’ Berger would, of course, in 1864, become Mr Annie Lascelles, but for the meanwhile they had just got as far as promoting a joint concert (17 June 1863) at the Queen’s Rooms and a second at the Hanover Square Rooms (19 May 1864), and Annie added to the continuingly successful ‘The Night Bird’ in her current repertoire another couple of Berger ballads in ‘Fallen leaves’ and ‘Monna’.

During the 1863 season Miss Lascelles was as much in view as ever, delivering music ranging from Mercadante (‘Ah, s’estinto’) to Langton Williams (‘Dreams at Sea’) and Clara E Murphy’s ‘The Meeting of the Waters’. She joined Jenny Lind, Lemmens-Sherrington, Montem Smith and Weiss for two performances of Handel’s L’allegro ed il pensoroso at St James’s Hall (1 May, 8 July, ‘And join with thee calm peace’, ‘Sometimes let gorgeous tragedy’), took part in Susan Sunderland’s Farewell concert at Manchester, sang the Messiah at Her Majesty’s Theatre on Christmas Eve (with Titiens, Wilbye Cooper, Santley and a chorus of 500) and the following night at Manchester’s Free Trade Hall (with Rudersdorff, Perren, Weiss) and in September made a rushed trip to Norwich to replace an ailing Bessie Palmer in Elijah and the Messiah at the annual Festival.

1864 began much as usual, with an appearance at Howard Glover’s first monster concert of the year, singing the Les Huguenots ‘No, no, no’ and Nancy’s line in the Martha spinning wheel quartet, and in May came the joint concert, at which a selection from Berger’s unproduced operetta, Milli, was performed by Lemmens-Sherrington, Annie, Perren and Ciabatta. At the said Ciabatta’s concert in June she joined Parepa and Sainton-Dolby to introduce a new trio ‘Le Spagnole’ by Pinsuti, and she took part in one of those all-star performances of the Mosè in Egitto ‘Dal tuo stellato’ which were a feature of concerts of the era. But mostly she plugged ‘Monna’ and ‘The Night Bird’ from one concert to the next. And on 13 August 1864, at St Mary’s Church in the Parish of Marylebone Sarah Annie Cobb ‘full age, spinster, daughter of George Cobb gentleman’ married Francesco (sic) Berger, composer of music – the above music, indeed – of the district of Holy Trinity, Brompton.

In one of his books of memoirs, Berger later wrote that on their marriage he requested his wife to retire from public performance, and she of course complied. In fact, it was several years before the nearly 40-year-old Madame Berger-Lascelles (as she now billed herself) more or less complied. She does seem to have retreated from the platform, after her marriage, until the several seasons on. In the years 1865-1867 her workload did not noticeably decrease.

At the beginning of December she restarted her Amateur vocal reunions at her ‘new residence, 3 York Street’, and I spot her out singing ‘Di tanti palpiti’ and ‘Quando a te lieta’ with the Maidstone Philharmonic society as early as 25 April 1865. A week later, she is introducing Berger’s latest ballad, ‘Serena’ at George Forbes’s concert at the Hanover Square Rooms, and the next night taking part in that annual Messiah of the Royal Society of Musicians. Her concert dates in May included a new appearance with Madame Puzzi (Ann Banks and Parepa were the other English names, in a sea of European ones), and after a few more outings with ‘Serena’, on 16 June 1865 the spouses Berger mounted their latest own show, at the frequently welcoming home of the Marchioness of Downshire. On 1 July Annie turned out at both ApTommas’s concert at the Beethoven Rooms (‘Serena’) and at the Benefit for the insane Antonio Giuglini for which occasion she launched a new song, Virginia Gabriel’s ‘When sparrows build’.

In September, the season over, her name appears in the press in a new capacity: in an advertisement for ‘Holland College, 2 Notting Hill Square…’ are listed the vocal instructors ‘for ladies of position, resident or non-resident’. Gustave Garcia, the veteran George Benson, Allan Irving and Madame Berger-Lascelles.

Between her new duties in Notting Hill and the Amateur Vocal Reunions -- which can be seen from their prospectuses to be musically considerable: one of them includes selections from the Stabat Mater and Elijah, Depret’s ‘Ave Maria’, Meyerbeer’s ‘Paternoster’, a Fabio Campana chorus, part-songs by Berger and glees by Bishop, and the students got to take five, while the instructress delivered solo Gounod’s ‘Nazareth’ and Blumenthal’s ‘I thought to be thy bride’ – Annie Berger Lascelles was thoroughly occupied, but she was still thoroughly visible on the concert stage. In 1866 she can be seen at Edwin Ransford’s concerts (‘When shall we meet’ with Parepa, the Blumenthal &c), at a rather more anglicised Mme Puzzi matinee, in W T Wrighton’s Ballad concerts singing trios with Parepa and Edith Wynne (Wrighton’s ‘O chide not, my heart’, Berger’s ‘Song for Twilight’, Gabriel’s ‘Under the Palms’ Abt’s ‘How sweet and soothing the vesper chime’, Henry Warren’s ‘Fair bridal of the earth’ plus duet ‘The Flower Gatherers’ with Wynne and Gabriel’s ‘Under the palms’), at Collard’s Rooms for Jules Mottes and Signor Fortuna, and of course in their own concert, given on 12 June at Hanover Square Rooms. Louisa Pyne topped the bill, Annie introduced Berger’s latest ‘At Midnight’ and ‘Under the Palms’ and joined with Miss Pyne and Eleanor Armstrong in the ‘Song for Twilight’.

The following season, finally, her public appearances did begin to shrink. She was occupied in ‘Afternoon classes for the practice of vocal music, ladies only’, ‘the half term of her amateur vocal reunions commences ... Spohr’s Last Judgement, Gounod’s Messe Solennelle, Rossini Stabat Mater and William Tell …' or at Holland College, where she had now been joined by Mrs Alexander Newton, on the teaching staff. But she was still trekking to Newport and Hereford with Macfarren’s ‘Waiting at the Ferry’, still singing with Madame Puzzi (Berger’s ‘It seems so long ago’), still doing the season’s concerts – Howard Glover’s, Trelawny Cobham’s, Caravoglia’s and so forth, and, on 14 June 1867, the spouses Berger produced their annual at the Hanover Square Rooms. It featured the septet from Tannhäuser and, once again, Louisa Pyne.

And now, forty past, Annie Berger Lascelles, more or less took her leave of the public platform, emerging each year from her teaching occupations virtually only for the Berger concerts. It seems that her powers were still complete, for the programme in 1868 (26 May) shows her singing the demanding ‘Pensa alla patria’, ‘O del mio dolce ardor’, ‘Les Souvenirs’ and Berger’s ‘Silent let thy love remain’, plus a ditty called ‘Pet Names’ by one Isabella, a duet with Italo Gardoni, and another – Berger’s ‘Warning Echoes’, which she had previously sung with Natalie Carola, with Luise Liebhart. In 1869 she introduced her husband’s ‘Golden Dreams’, but clearly not just that, for their 1871 (15 May) programme has Annie doing the Aria di Chiesa (Stradella), ‘Ah s’estinto’, Pinsuti’s ‘I hear a voice’, Gabriel’s ‘Only’ and duetting ‘Ebben per mia memoria’ (Gazza ladra) on a bill including Elena Corani, Katharine Poyntz, Henry Nordblom, Léonce Waldeck and Harley Vinning. In 1873 (2 July) she was advertised to take part in a charity concert for a Broadstairs Orphanage, singing ‘Fanciulle che cuor’, Berger’s ‘My World’, Alice Sheppherd’s ‘Only the River Knew’ and the Rossini trio ‘Gratias agimus’.

Quite how long the Berger’s own concerts went on, and quite how long Annie kept singing, I do not know. But I do have before me an advertisement for Francesco Berger and Madame Berger Lascelles’s morning concert at Willis’s Rooms on the 28 May 1888 at 3 o’clock. The participants are Madame Fursch-Madi, Mdlle Marie de Lido, Madame Berger-Lascelles, Mr Iver McKay and Herr Carl Mayer. Berger and two of his pupils play. So, the critics who in early days praised Annie’s voice, but by inference criticised her method, were wrong. Here she is at sixty years of age past, still up there doing it, alongside the likes of Fursch-Madi.

Francesco Berger’s ‘après-midis instrumentales’ continued for many, many years. Annie’s singing equivalents seem to have ceased rather sooner. And, whereas Annie’s career was now winding down, her husband’s was taking on another dimension. From piano playing and the composition of such parlour pieces as ‘Serena’ (although he had been guilty of an opera in his youngest years), he went on to become a respected teacher of music at the Royal Academy of Music and the Guildhall, and most importantly to become the honorary secretary of the Philharmonic Society, with all that meant in the way of influence and of contacts with the high and the mighty of the musical world. He lived to be 98 years old, and reminisced largely in two volumes.

Sadly, he lived the last, reputation-rich quarter of a century of his life as a widower. Annie Berger died at the age of 80 in 1907. And, at last, on her death certificate, that fact of age – so staunchly denied down through the years – had to be admitted.

Annie Lascelles had a fine career. She clearly had a genuine contralto voice (although I have seen one contemporary reference to her as ‘a fine mezzo-soprano’ which seems to go against all others) of considerable quality. Her husband’s memoirs affirm that she was a particular favourite of Queen Victoria, and the royal engagements (of which there were very likely more) which she fulfilled seem to confirm that. Miss Cobb from the Bell Inn, Nottingham, by any other name, was a model Victorian vocalist.

No comments:

Post a Comment