This is a story of success. No bumps, no scandals, no husbands, just pure music, from Pennsylvania to Paris, from Bristol to Boston ...

PHILLIPPS, Adelaide [Maria Marianne] (b Bristol, 26 October 1832; d Karlsbad 3 October 1882).

One of America’s most admired contraltos of the Victorian era.

One of America’s most admired contraltos of the Victorian era.

I set out, originally, to avoid writing articles on folk who had previously had a complete biography published about their life and their career. But, I was well on my way when I discovered that Adelaide had been already ‘done’. And rather beautifully done. Mrs R C Waterston’s little book (Adelaide Phillipps: a record) is not so much a biography as a loving memorial to a friend, occasionally a little heartfelt and gushing but rarely in error on the bits of the singer’s life on which she had material or experienced in person. Since these bits include chunks from Adelaide’s youthful letters home, from Europe, the early part of the tale is fascinating. The later part is selective and includes many reviews and testimonials. The best ones. So I would say to anyone interested in this vocalist, read the first half and the end of Mrs Waterston and fill in what gaps there are from here.

Adelaide Phillipps – that’s double 'p’ not single – was actually British, born in St Paul's, Bristol (some, curiously, say Stratford-on-Avon) in a year which is, everywhere, given as 1833. As her birthday was given as October 26, and as she was christened in April 1833, it appears 1832 might be nearer the mark. Anyway, somewhere between Alfred (b Trinity St, x 31 January 1830) and Frederick Henry Richard (b Redcliffe St. x 29 June 1835).

Her father was Alfred Phillipps, a chemist and druggist, of 105 Redcliff Street (‘cheap cigars…’), her mother, née Mary Rees, in partnership with her sister, Ann Rees, a dancing and calisthenics teacher (‘Mrs Alfred Phillipps begs to make known to the Gentry of Bristol, Clifton and their vicinities that her annual ball will take place on Wednesday Jan 8 1834 at the Royal Gloucester Hotel Clifton ..’ 25 Portland Square…).

We are told that Adelaide came to Canada, and then America, with her family aged, variously, 6 or 7. Well, it certainly wasn't 6. The Phillip[p]ses are still in Bristol in the (April) 1841 census, and on 7 August, Mrs P is announcing her Academy’s new term, to start in September 1841 … so … again, perhaps a year or so out? And, unless it was sister Ann advertising in August, it seems as if it may have been a reasonably sudden decision.

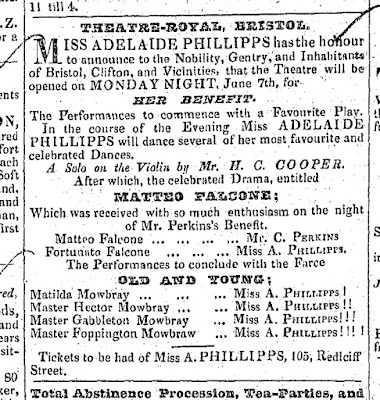

What even Mrs W doesn’t tell us, is that, before that date, Adelaide had already gone on the stage. Mother's teachings saw her up on the boards aged six: performing a highland fling at 'in character' at Coleman Pope's Benefit (22 April 1839), at another Benefit (15 June 1840) she danced 'two of her most celebrated pas'. At the same Theatre Royal, Bristol, 6 May 1841, she appeared in Henry Cooper’s Benefit ‘the celebrated Miss Adelaide Phillips (sic) who has been received with so much enthusiasm and who is not yet eight years of age’ played the title-role in Bombastes Furioso. A few days later, at Mrs McCready's Benefit, she danced the Cachuca 'à la Duvernay' and 'the precocious and elegant danseuse was honoured with an enthusiastic encore'. On 24 May, she came out in the drama Matteo Falconi with Charles Perkins, stage director of the Bristol Theatre Royal, at his Benefit, and 7 June 1841, a Benefit for her was held. She played the four different roles in the farce Old and Young, repeated Matteo Falconi with Mr Perkins and ‘danced several of her most favourite and celebrated dances’, while the same H C Cooper ‘leader of the band’ (and, soon, much more) played the violin. She won ‘reiterated plaudits’ for what was rumoured to be her last performance in the city.

So, all in all, it looks as if the Phillippses left for Canada in the later months of 1841, for in January 1842 the 9 year-old girl appeared at Boston’s Tremont Theatre, giving, again, her protean farce (with song and dance).

She made a New York debut on 1 May 1843, billed as ‘the best danseuse in America’, on a programme at the American Museum alongside a protean actor, a ballad singer, a Model of Paris, the Sea Dog of Newfoundland and a 20 foot serpent, and remained on the bill for over a month, during which time Tom Thumb also made an appearance.

On 25 September 1843 she appeared at the Boston Museum playing the famous kiddie part of Little Pickle in the musical comedy The Spoiled Child, and thereafter she worked as an actress and dancer in Boston, through till 1851 (Benefit 21 June, 4 July Rose in Love in all Corners). By this stage, her singing voice had been developed, by local teacher Sophie Arnoult, to a point where it was thought advisable for her to go and study in Europe, and the local wealthies got together to raise the money necessary, which was topped up by a donation of $1,000 from none other than Jenny Lind. It was said to be at the prima donna’s behest that she headed for London to study with Garcia, who already had quite a few Bostonians of varying degrees of talent in his stable (Elise Hensler, Harrison Millard, ‘Edoardo’ Sumner et al). Garcia was quoted as saying that Alboni and d’Angri were the only contraltos in the world and that ‘therefore he wishes his new pupil, Adelaide Phillipps, whose voice he finds to be a first class contralto to enter this interesting field’. So Adelaide ceased to be a soprano and became a contralto.

After some two years in London, in the autumn of 1853, she headed for Italy and succeeded in winning an engagement – without, she wrote home, having to pay for it as most aspiring vocalists did – at the Teatro Grande, Brescia in Semiramide (5 November)

Mrs Waterston gives the details of the occasion and the fine reviews: ‘La Signorina Fi[l]lippi (Arsace) por giovane e bella, ricca di forte e ad un tempo dolcissima voce, intuonata, flessibile, estesa, di vero contralto, educata al bel canto dal sommo institutore Emanuele Garcia desto un tempo piacene e marviglia. Lodossi pure il suo distinto ed elegante modo di porgene e 1'anima di cui si mostra dotata e divenne in breve la delizà del publico, che le fece le piu clamoroso applausi.’ (La Fama). Porgene?

Her struggle through the complexities of the Italian operatic establishment to win more engagements is vividly related by Mrs W. She appeared at Crema over Carnevale, at Milan in concert (‘Ah quel giorno’) and at the Teatro Carcano singing her Semiramide, ‘Non più mesta’ and the last part of Vaccai’s Romeo e Giulietta. On 4 May she gave a performance at Rovereto. But that was it. She quit Italy and returned to America to be greeted with news of her mother’s death.

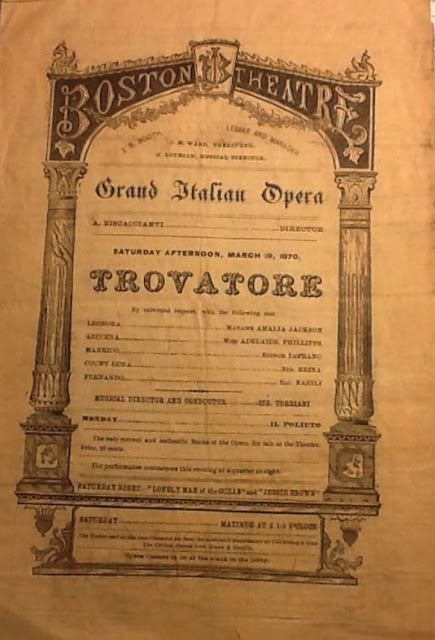

She appeared in Boston in concert during October and November of 1855 ('Una voce', Marguerite d'Anjou, Paër barcarolle, 'Che faro'), sang her first Messiah with the Mendelssohn Choral Society at the Tremont Temple (9 December, 'she is one of the few Americans that have really profited from a residence in Europe'), another with the Handel and Haydn Society (23 December) and, in the new year, joined the operatic company headed by Anna Lagrange, replacing no less a vocalist than Constance Nantier-Didiée. She appeared, in March, for the first time on the American operatic stage, at Philadelphia, as the Marchioness in Linda di Chamonix and Arsace in Semiramide and, six days later, at New York’s Academy of Music as Azucena in Il Trovatore alongside Lagrange, Brignoli and Amodio. After concerts in New England, she joined with the same troupe for more performances (Azucena, Maffeo Orsini in Lucrezia Borgia etc) and, in 1857, with another Maretzek troupe headed now by Marietta Gazzaniga. with whom she again played Rosina in Il Barbiere di Siviglia (‘good-looking, voluptuous… a fine voice and an excellent musician’) with the interpolation of ‘Non più mesta’, Maffeo Orsini, Federica in Luisa Miller, Pierrotto and Azucena (Niblo’s Gardens, 14 April 1857). In between the operatic seasons, she returned to the concert platform.

In 1857-8, Maretzek took his troupe to Havana, after which Adelaide joined with Anna Lagrange and then Pepita Gassier in further opera troupes, repeating endlessly her Rosina, her Orsini, her Azucena, her Pierrotto. When Mme Gassier sang Gilda, Adelaide was a notable Maddalena leading a critic to comment, after Rigoletto: ‘We doubt if there is another artiste on the stage who has improved so rapidly as Miss Phillips. Her voice is now so ably trained, and of such delicious quality, that we very much doubt if there is another contralto who can greatly surpass her’.

1859 was spent partly touring under Ullman (Martha in Nancy et al) and she played the title-role in Dr Thomas Ward’s opera Flora, or the Gipsy’s Frolic (2 June) which included in its cast Lucy Escott and Catherine Lucette, and which played for but two performances. In 1860, however, she suffered several bouts of illness, said to be due to her time in South America. Nevertheless, she had time for some operatic work – playing Nancy to the Martha of ‘Miss Patti’, for Ullman, and with Adelaide Cortesi’s troupe, where her Azucena was loudly praised: ‘Immense effect - more brilliant than we ever heard her before’. The Bristol papers, which had loyally charted their contralto's progress from afar, gotin a wee bit of a muddle this time, a telegraphists finger led them identify 'Miss Adelina Path' with Adelaide.

At the end of 1860 she was out on the road in yet another opera troupe with Pauline Colson as prima donna, Brignoli and Isabella Hinckley, with which she got to play, beyond her regular roles, Bianca in Il Guiramento, and Sinaide in Mose in Egitto. In 1861 it was Maretzek again (Ulrica in Un Ballo in maschera) until she left America, to return to Europe. This time, she was away for nearly two years, and once again she suffered somewhat from the frasques and intrigues of opera managers.

She was hired for two years by Merelli for the Paris Théâtre des Italiens where, once more as Signorina Fil[l]ippi, she gave her Azucena to the Manrico of Mario, the Leonora of Rosina Penco and the Luna of delle Sedie (19 October), then her Ulrica alongside delle Sedie and her Arsace to the Semiramide of Penco. When she sang the page, Smeaton, in Anna Bolena with Alboni, Le Menéstral nodded 'Seule Mlle Filippi a secondé les magnifique élans de Mme Alboni'. From there she went, with Merelli, and Anna Lagrange once again, to Madrid and Barcelona. But, while Merelli was away, the Parisian directors managed to get him sacked and, with Merelli gone, so too was Adelaide’s two-year contract. She toured with the irrepressible impresario through Belgium, France, Holland and apparently as far afield as Poland. I see them in Lille performing Il Barbiere di Siviglia: 'Rosine était représentée avec une gracieuse espièglerie par Mlle Adélaïde Filippi dont la voix de mezzo-soprano est pleine de charme et d'habilité'. She sang 'Non più mesta' and 'Il bacio' in the lesson scene. I later spot her is Prague (September 1862) and in Pesth where she sang Zerlina in Don Giovanni. She finished her European visit with six weeks at Lille, and then headed back across the Atlantic.

She returned home to more of the same activity: another operatic visit to Havana, a Strakosh tour with more Brignoli, more Barbiere and now playing Norina in Don Pasquale, more concerts (‘Una voce’, ‘Che faro’ ‘the finest contralto now on the lyric stage’) and oratorios and, in 1865, a trip to the west coast.

In 1866 she partook of another tour with Maretzek with Carlotta Carozzi Zucchi and Clara Louise Kellogg as prime donne, and a season at the Academy of Music where she sang, amongst her usual roles, Nidia in Petrella’s Ione alongside Enrichetta Bosisio. The following year she teamed once more with Anna Lagrange and Brignoli for a repeat Strakosch round, during which she sang the Leonora of La Favorita.

As ever, the operatic seasons, longer or shorter, were interleaved with concert engagements, of which the Boston Music Festival of 5 May 1868 was the most sizeable. But, shortly after that, she said ‘farewell’ again (‘Lascia ch’io pianga’, ‘Son leggero’, Saffo duet with Gazzaniga) and headed back for another of her periodic visits to Europe. But bad luck seemed to dog her times citra-Atlantic. Signed for another two-year contract in Paris, she was obliged to give it up when her father became ill. He was to die on 16 October of the following year.

She sang with Parepa in the Boston Peace Jubilee (‘Non più di fiori’),

and 1870 gave her another round of opera, and a substantial tour with her own concert party, supported by the celebrated cornettist Levy and (mostly) Jules D Hasler (baritone), which lasted into 1871. That year was a year spent concertising in America and Canada at the head of variously compiled groups including violinist Sarasate, tenor Charles Lefranc, basso Johann-Friedrich Rudolphsen and ‘her protégée Cornelia Stetson’, but by Easter 1872 she was back on stage, appearing with Parepa, Wachtel and Jenny van Zandt and the Rosa-Neuendorff company as Azucena, Maddelena et al.

|

| Sarasate |

The Adelaide Phillipps Concert Company, featuring violinist Camilla Urso, toured in early 1873, before Miss Phillipps left for Europe ‘to go climbing in the Pyrenées’, and to see sister Matilda, whom she had placed with Garcia in London to be similarly transformed into a successful contralto vocalist.

On her return she appeared in concerts (‘Absence’, ‘Ah, mon fils’, ‘Pardon me, my God’, ‘Soave sei amato bene’) and then, in 1874, she launched the Adelaide Phillipps Opera Company, a company which had the surely unique particularity of carrying no lead soprano. Tom Karl, Orlandini, Bacelli and Locatelli were the other featured artists. They played Il Barbiere di Siviglia and Don Pasquale, and Adelaide took the roles of both Rosina and Norina.

In early 1875 it was announced that she was quitting the stage, and great festivities were planned to mark the occasion. However, the announcement was rather premature and the company continued on its rounds, ending up, for a week, in a rather more sizeable shape, at New York’s Academy of Music (14 February 1876) where she played Rosina, Azucena, La Favorita and Tisbe in La Cenerentola. She was Tisbe, because the role of Cinderella was reserved for sister Matilda – now become ‘Mathilde’ – making her first appearance on the American stage. The company played further dates with the English soprano, Maria Palmieri, and her tenor husband, Tito, adjoined, to allow them to play Semiramide and, announcedly, Le Comte Ory, before it shuttered and Adelaide and Matilda returned to the concert platform.

In 1877 she went out with J C Fryer’s Charles Adams-Eugenie Pappenheim company, but problems surfaced in New Orleans when the soprano was said to have taken umbrage at the popularity of the contralto and gone ‘sick’. Truth or journalism, Adelaide stayed with the troupe to New York, but seemingly with a reduced workload. She would also premiere the Verdi Requiem in Boston with Pappenheim and Adams in 1878, so any breach cannot have been too dramatic. In the new year, she took another trip to Europe and south-west France and, when she returned, she picked up her own company, headed by Tom Karl, for further dates, before, in 1879, she finally put the company to rest.

|

| Tom Karl |

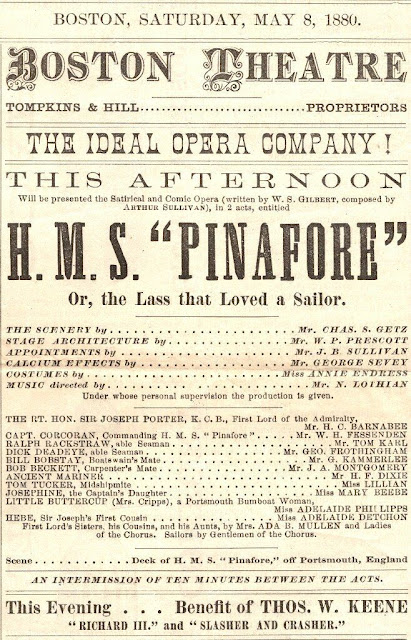

In 1879 Effie Ober, agent, of Boston put together a very classy troupe to play a truthful version of the latest megahit, HMS Pinafore, currently being purveyed round the country by all sorts of approximate rag-tag-n-bobtail groups. Local vocal comic Henry C Barnabee, the area’s outstanding bass Myron V Whitney, Tom Karl and the rather strange soprano Dora Wiley were to head the production, and Adelaide Phillips was cast as Little Buttercup. In the event Miss Wiley announced a double booking and the young Mary Beebe took over as prima donna and, come opening night, there was no Miss Phillipps either. One of her periodic illnesses had struck her and Isabella McCullough (sometime Mrs Brignoli) stepped in.

However, Adelaide soon returned to ‘her’ role. The Bostonians showed that the only way to play Gilbert and Sullivan was accurately and at a high standard: their production was a huge success, netted $42,000 in six weeks, and the to-be-famous Boston Ideal company was on its way to a position as America’s top light operatic company.

The tale of the Ideals has been succinctly told by Barnabee – the base member, and eventual co-owner of the troupe -- in his autobiography, My Wanderings. Suffice it to say that Adelaide – with her acting and singing skills – was an immense success as an ‘Ideal’, as she went on to play Fatinitza, Ruth in The Pirates of Penzance, Germaine in Les Cloches de Corneville, the Queen in The Bohemian Girl, Lady Sangazure in The Sorcerer, and the title-role in Boccaccio. At the end of the 1881-2 season, she took another trip to Europe, for her health. She was at Karlsbad, for the waters, when she died in October of the year. Her body was brought home on the steamship Werra, on its maiden voyage, to be buried at the old Winslow Burying Ground at Marshfield alongside her brother, Frederick, an army surgeon who had died of a tropical disease, 21 November 1879. The other members of her large family, whom she is said to have largely supported by her operatic earnings, would follow: Alfred (8 October 1901), George (23 July 1906), Adrian Wooles (30 January 1907), Edwin (26 December 1919), and Matilda (d Marshfield 10 March 1915) as well as foster-sister, Arvilla Corbet (d Massachusetts Hospital 27 October 1906), who had married Adrian and who had been Adelaide’s companion on her early European trip.

‘Mathilde’ made a good career as a vocalist in the shadow of her sister. In 1880 she was on the road with the Tagliapietra Opera Company (‘her contralto voice all aglow ... floated out over the audience like a silver trumpet’ La Favorita) for the brief time of its existence, and in 1882 she took up Adelaide’s place as contralto with the Ideals (Pedro in Giroflé-Giroflà, Lady Jane in Patience, Gypsy Queen, Nancy in Martha etc). She appeared with the so-called American Opera Company, and then joined Strakosch to tour with Annis Montague and Charles Turner in 1886. In 1887 she appeared with the American National Company at the Metropolitan Opera House and in San Francisco (Martha in Faust). She also performed in oratorio and concert, notably in the 4th Boston Festival in 1877 (‘a strikingly favourable impresssion’).

Arvilla, Adrian and Frederick also partook of the stage in their young days, appearing in a dance act at the Boston Museum.

No comments:

Post a Comment