Cold spring morning. Fire on. And my friend Jeff Clarke from Opera della Luna sent me a scan of this delightful 1856 playbill. 1856. My best period .... and I haven't heard of a single person is the cast lists! There is a good reason, however. The bill is from Mr Victor Isaac Hazelton's Bower Saloon,in Westminster Road, down on the Surrey side. A 250 seat house pendant to his Upper Marsh pub 'The Duke's Arms', not famed for classy entertainments. Or classy casts. You could enrol as a 'pupil' with 'appearance guaranteed'. It spent much time housing amateur productions.

It is also a bill for a one night Benefit performance ... a mish-mash of 'popular' bits and pieces ... melodrama with trained dogs, dancing, mime-drama, a contortionist and a version of

Der Frieschutz (note the spelling!) with a cast of four men and no singing. The singing was confined to a 'grand concert' which was apparently made up largely of comic songs.

I was curious, however, to know who were these folk appearing on such a programme. Were they professionals? Did they have careers in the theatre or the music halls? Or, were they so insignificant as to defy any kind of research? I started at the top ... the Beneficiary ...

Richard Henry KITCHEN or DUNN (b Ann Street, Lambeth 25 June 1830; d Langton Rd, Brixton, 30 June 1910) was a dancer, a ballet master, swordsman, a pantomimist and clown, who worked for over half a century on the stages of Britain, in -- it seems -- just about any capacity. In the 1860s, he teamed with Tom Lamb and his performing dogs doing dog dramas (

The Woodman and his Dog, The Forest of Bondy &c). He married Emma Elizabeth Burry, and one of their sons made a considerable name for himself as a musical comedian as Fred Kitchen (1872-1951).

Thomas LAMB (b Chatham 27 September 1818; d before 1895) was on the bill too, along with his original partner *** CHAPPEL. I see them as early as 1851 'with their wonderful dogs' at Manchester, and thereafter largely in Music Halls and Theatres in the northern part of England. By 1860 Mr Chappel has been succeeded by Mr Kitchen and Tom's little son (who would later dub himself 'Tom Melrose') is featured. I last see Lamb and Kitchen together performing at the Victoria (The Life of a Tramp, Tom and Jerry) with dog Carlo in 1870. Lamb and Carlo are back at the Bower in 1872 ...

There may have been a closer link between Kitchen and Lamb. Lamb married Jane Dunn, daughter of an East End beadle. Kitchen also went by the name of Dunn. Odd. I don't know what became of Lamb. But when the son died, aged 44, in 1895, he was referred to as 'late'.

Of the concertgivers, I cannot discover Miss S Pitts or Josh Bowmer, but the others leave more or less trace.

Selina PEARCE was a child actress. I see her in 1854 playing Topsy to the Eva of the Eva of Clara St Casse at the Theatre Royal, Newport. 'An intelligent child about 7 years of age'.

Albert GORDON was a tenor gentleman apparently from Dover where I spot him in 1855. He played Tom Tug in The Waterman at the Bower, Osbaldistone in Rob Roy at the Victoria (1856) and I see no other.

Henry WAITE (b Bristol 1829; d Brixton 8 January 1900) was a 'comic vocalist and delineator of Hibernian Drollery': in another words an Irish stand up comic. The son of a Bristol publican, he turns up around 1857 singing his comic songs in suburban London: Clapham, Marylebone, Poplar, East London, Camberwell, Islington, the Green Gate Saloon in the City Road ... sometimes in the company of such notables as Elijah Taylor, W G Ross, Ambrose Maynard, the Barnum children. Harry was a married man, with a stepson and two daughters, Nettie and Emma, and in the early 60s wife Harriet (née Gibbs) and then the daughters joined Harry in the act.

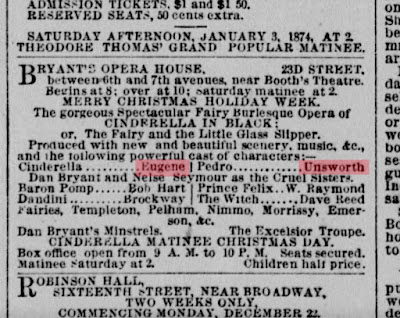

Harriet withdrew after a decade (she would die 321 Albany Rd, Camberwell 13 December 1886) and Harry soon after, by which time it was clear that the main attraction of the group was the girls. Each Christmas they were topbilled in good class pantomimes, and in 1874 they visited America and topbilled at Tony Pastor's (Hattie, Nettie and Emma, the Waite Sisters) and the Chicago Theatre.

In 1878 Nettie married William Nelson Govett, better known as Will Poluski, with whom she had starred in several pantomimes, and in 1886 Emma wed another performer, Thomas Andrew Harlow. On her marriage certificate, she described her father as 'grocer'.

The Poluski daughters continued the tradition as 'Ethel Love' and 'Lottie Walton'.

Master D Moore, was Daniel MOORE (b London c 1847; d Aston 12 June 1874) and was a genuine juvenile. He would have been nine or ten years of age at the time of this concert, and it is the first engagement I see in his young life. In 1858 he played four months at Chatham in a double act with his father and, here again, it was clearly the youngster who was the feature 'very clever dancer and player of the violin and banjo' 'clog dancer and violinist', 'duettists', 'American negro delineator, vocalist and instrumentalist', 'negro comedians', 'sketches of life', 'spade dancer', 'duologue artists', 'songwriter' ('A sporting life for me') ... young Dan turned his talents to whatever the latest fashion demanded. Alas, at the age of just 27 he fell ill of 'consumption' and died ...

Further down the list 'Young Devani!'. Yerrrm. How young? There are several, all related and all in the same line of business. Gymnastics, especially contortionism. 'The greatest Bender in the World'. Their name, of course, was not Devani and nor were they in any way exotic. Their right name was Longstreeth and they were a pure product of the Lambeth Marshes. Father was Isaiah James LONGSTREETH (b 1839; d Lambeth 1888), mother (who didn't contort) was Jane Frances née Moore. So Isaiah would be 17. That's 'young'. Looks good, but then who is 'Mons Devani' in 1850 in Ireland, 1851 in Birmingham, 1852 at Cremorne ...? And which Devani visited Australia with the Risleys in 1859? Isaiah, surely. Not his sons, who both followed the bending trade -- Leon (b 1861) and Eugene (b 1867). So I am pretty sure that Isaiah was 'Gabriel Devani'. When he had finished bending, he became 'clown and pantomimist'.

In smaller print is Richard Henry MENDHAM (b Ipswich c1823; d Stangate 31 March 1874). Mendham was employed to be stage director and play bits. I see him performing as far back as 1848, and he went on to play drama, pantomime and comedy at the suburban theatres, and to produce seasons in Monmouthshire with H R Stephens .. He married actress Rose Archer in 1857, but she died in 1862 and he the following year.

So, in larger print, but lesser nevertheless than the dogs Nero and Carlo, we have Mr A Saville, Mr H Hall (with his little son Tommy) and Mr J Hicks.

To my surprise, Mr Saville turns out to be Alfred SAVILLE (b Colchester 26 November 1812; d London 27 June 1885) otherwise Alfred Faucit Saville, of the well-known theatrical family (think, Helen Faucit). Alfred had a long, solid career in the provinces and above all the suburbs playing character/'old men' parts at such as the Victoria, the Pavilion and the City of London in such potboiling thrillers as The Lonely Man of the Ocean, The Soldier of Fortune, The Soldier's Bride, Woman and her Master, The Lighterman of Bankside, The Prisoner of Rochelle, The Vow of Silence, The Lucky Horseshoe and just occasionally in Surreyside versions of Shakespeare (Gloucester in King Lear, Stephano in The Tempest) with the likes of N T Hicks.

Hicks. So, Mr J Hicks? Surely not Julian Hicks, the well-known scenic artist. But I think it is! The father, not the son. Julian Shurlock Bult HICKS (b Islington 2 March 1836; d Camberwell 24 December 1882). Rather than the pianist and concertina-player touring with Sam Cowell?

Anyway, our one is playing at the Pavilion, Whitechapel Rd in 1854 (Woman and her Master), at the Victoria in 1855 (Ned Cantor) alongside Saville, but by 1860 is painting the scenery at the Haymarket and ... the Victoria. And from there, he continued to the peak of his profession. Of course, there may be a third Mr Hicks, but I give myself a 90% chance of being right!

Harry HALL and his little son Tommy escape me. The only Harry Hall I know in the 1850s is the famous equestrian painter. I spy them just once more in 1859 ...

Mr Fernandez? I guess he's the Mr F in the company at Gravesend earlier in the year. Then at Reading. By 1858 he is at the Surrey playing young lover parts, on one occasion opposite the great Henry Phillips in Auld Robin Gray, and he soon begins to rise up the bills as he progressed to the Grecian, then back to the Surrey (Cassio to the Othello of Creswick, Phoebus to his Quasimodo). So he's James FERNANDEZ (b St Petersburg 1835; d 1 Carlisle Place, London 13 July 1915) son of Thomas Fernandez of the Stationery Office, husband of Georgina Robertson, 'juvenile trgedian and light comedian' and by far the -- eventually -- most memorable participant in Mr Kitchen's Benefit.

Well, I'm finding more folk here than I expected. And here's another!

[John] Charles RIDGWAY (b Portsea 1828; d Fletton 11 August 1859) specialised in 'music, dancing and calisthenics'. He was a skilled violinist, and specialist player of Pantaloon ... alas there is more than one Mr Ridgway around. Surely he is not the one in the Adelphi panto in 1842. Or fiddling ('Master Ridgway') with his elder brother in Portsmouth in 1843. Ah! Master John Ridgway of Portsea .. deputy leader of the band at the Windsor Theatre ... his brother Joseph professor of the harp is leader at the Dorchester Theatre, md at Guildford , harping at Ryde ... Master John has formed an amateur band at Portsea ... he has left Portsea to join Mr Theodon, Theatre of Arts, Stamford ...

So when do the dancing and calisthenics come in?

Perhaps it is he dancing at Glasgow in 1850. Ah! No, that's Mr T Ridgway 'the celebrated clown'. Mr C is playing Pantaloon at Hull. So it is Mr T choreographing the Grecian panto of 1851. And Mr C who moves to Stamford and Spalding to teach, play, concertise ... 'of the Italian Opera, His Majesty's Theatre'. But here's Mr J Ridgway 'of the Italian Opera and pupil of Mr Coulon' teaching the schottische in Southampton ... six private lessons for one guinea. And Mr and Mrs Ridgway teaching the new dance 'Pop Goes the Weasel' in Birmingham.

Well our Mr J C had indeed just got married to one Eliza Nelsey. So I imagine that's them. Or is he the Mr Ridgway dancing harlequin at Brighton? The Birmingham one seems to be Mr J H. But it is definitely he in Stamford.

He was Pantaloon at Reading in 1853, at the Marylebone Theatre in 1855, at Portsmouth in 1857.

Things did not go well for Mr Ridgway. His wife was delivered of a baby boy who died in infancy. Then he went for a swim in the River Nene ... and drowned. He was 31.

And who, may I ask, was the dancing Marion Ridgway? Eliza?

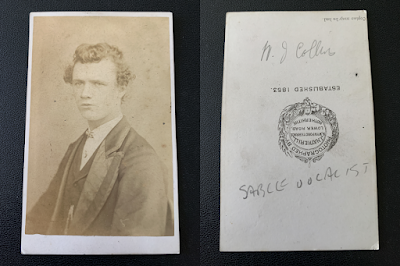

Alfred Shaw, Mr Morrison, Mrs and Miss Collins, 'Mis Brunette', W Dean, .. enough. Now, at least this playbill means something. Performers from the minor theatres putting on a show ... one night only.

Next day, Bryan Kesselman writes ... "There was a Joshua Bowmer (musician) who married Harriet Gill Turner in 1842 ... in 1863 .. entertaining in Cape Town - Mr and Mrs Josh Bowmer's utophic (sic) entertainment in addition to their comic singing was much applauded"

That's he! Joshua Bowmer (b Brixton 1823; d London 1884). Son of an exciseman. Brother Henry was also a musician. I see by 1881 Josh has become a house painter.

Look what's surfaced! The Forest of Bondy on the southside again. And with T P Cooke in the cast!