‘Former Great Tenor Dead’ trumpeted the New York Times on 8 May 1905. The New York Herald, not to be outdone, trumpeted too. And papers round the world, as papers did and do, picked up the story …

And almost every word of it was the most egregious poppycock.

Edoardo Rubini Swynfen Jervis, they claimed, had been first tenor at St Petersburg and Paris, he had taught music to the English princesses, and to a long line of star vocalists from Lucca, Marimon, Volpini, Cotgoni and Campanini to Joseph Maas and ... who? Scalisi? He had taught at the London Academy of Music … and he had come, at last, to New York where he died, destitute, at number 115 West 106th Street.

Was any of it true? Well, just a little. He did teach, briefly, at the London Academy of Music. It was probably the best teaching job he ever had. And Scalisi? Madame Scalisi was his sister, who achieved much, much more in music than he ever did and it is for her, certainly not him, that the Jervis family got this little piece in my Victorian Vocalists collection.

RUBINI, Fanny [Jervis] [JERVIS, Fanny] (b Lucca, Italy c1847; d 8 Church Street, Shoreham by Sea 13 December 1915)

However, ‘Edoardo’ is responsible for much of the mythology surrounding the family, so a quick glance at his pretensions won’t hurt. ‘Rubini’? ‘Swynfen’? The suggestion here is that there is some connection, on the one hand, with the famous tenor G-B Rubini, and on the other with the aristocratic family of Lord St Vincent, rightly named Jervis, and with whom ‘Swynfen’ was a much-used additional name. True or false? My automatic reaction was to say ‘false’, but there just may be a smidginette of truth in there. So I went a-searching.

The father of this family was a portrait painter from Sheerness, by name John Jervis. The 1861 census says ‘Jarvis’ which, if true, would ruin the whole story, but other documents all say Jervis, so I allow him the benefit of that doubt. Mr Jervis obviously practised his painting outside England, for at some stage, probably in the late 1830s, he married an ‘Italian’ singer, and their children, born in the 1840s and 1850s, were all born in Italy. I say ‘Italian’, for Mrs Adele Eugénie Jervis was actually German, born in the city of Laibach (ie Ljubljana) around 1813, although she apparently worked under the name of ‘Signorina Rubini’. If she had no right to it (and it was, later, insisted that she was ‘of Italian parentage’) it was, given the propinquity of the great tenor Rubini and his French wife née Adelaide Chaumet (Mme Rubini-Comelli), a rather tacky thing to do. It has been related that a certain singing Mlle [surely not Sophie!] Méquillet of the 1830s took her master’s name in ‘homage’: If this is true, I suppose it could have been she. But it sounds rather fishy.

Since the four children of this marriage were all born in Italy: Edward allegedly in Rome in March 1841, William about 1843, Fanny at Lucca in 1846 or 7, and Adele in Florence in 1857, I cannot know precisely how and when they were christened, but the 1861 census entry for 12 Elm Terrace, Kensington, shows the three younger children listed with just one simple Christian name apiece. Jervis. No Rubini, no Swynfen.

My first sighting of the Jervis children as performers is in 1855. A little squib in the English press mentions that ‘a Master Jervis and his sister Mdlle Fanny have been giving concerts in Florence with great success’. Yes, there they are, 5 May 1855, at the Sala d’Arte ‘il giovanetto Odoardo Jervis e la di lui sorellina Fanny’. They are playing, not singing: the vocals are supplied by the Irish soprano Elena Corani (née Conran).

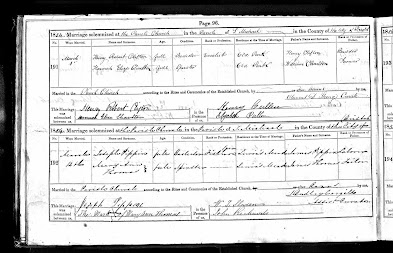

The Jervis family must have returned to Britain soon after Adele’s birth, for, on 11 July 1859, The Times announced: ‘The little pianiste, Fanny Rubini, pupil of her mother, Signora Rubini, has the honour to announce that she will give a grand morning concert this day (by kind permission) at the residence of Mrs Elliott Macnaughton, 46 Eaton Square. To commence at 3 o’clock. Artists: Mme Rieder Schlumberger, Signora Alba, Signori Marras, Crivelli, Corsi, Ciabatta, Giulio Regondi and Mr Blagrove. Director: Signor Campana.’ The next week ‘the young Italian pianist’ appeared at Giacinto Marras’s concert.

‘Fanny Jervis Rubini’ followed up this debut with another concert the following year (27 June 1860) in which brother, Edoardo Jervis Rubini, also played and conducted, and at which Catherine Hayes sang, and again in 1862 (21 June) and 1863 (2 July). By 1865, I notice, cartes de visite of ‘Miss Rubini’ were being published for sale, and, by 1866, she was well enough considered to be engaged, as replacement for Marie Krebs, from 1 October, as pianist at Alfred Mellon’s series of Covent Garden proms ('She played Thalberg's fantasia on L'Elisir d'amore and was rapturously encored', 'A young pianist of most refined taste and with the specialty of a delightfully liquid touch' 'fait fanatisme .. un talent sérieux' ) . In January 1867, I spot her playing both at the Popular Concerts at Her Majesty’s Theatre ('a pianist of no ordinary stamp') and as guest with the London Glee and Madrigal Union. Although she had sung in private homes since 1867, it is only in 1869, that I spy Fanny out for the first time as a vocalist, when, in a Dublin concert, having given her keyboard items, she also delivered the Faust Jewel Song.

Things seem to have moved briskly from there, but the family moved out of England, and on to the Continent, and my sightings of Mlle Rubini become episodic. In 1870 I spot her singing in concert in Paris. She is, the Paris press say, on her way to an engagement at the Pergola Theatre in Florence. ‘Vingt ans, expressive et charmante personne, jolie voix, du style, un vrai talent de musicienne, voilà certes de quoi se frayer une première place sur nos scènes lyriques’. Later, the report is that she is ‘studying in Florence’. And that ‘Miss Fanny Jervis who had previously made a favourable impression by her singing in the fashionable reunions of Florence, appeared at the Pergola Theatre some nights since in La Sonnambula and made a very successful début’ (‘haben wir für Fräulein Fanny Jervis Rubini die besten Hoffnung’ ‘Frln Fanny Jervis trat im Pergola-Theater mehrere Mal in der Sonnambula mit grossen Beifall auf’.) She is, in any case, doing well enough that ‘Edoardo’ and ‘Guglielmo’ Rubini, music teachers in London, see it worthwhile to advertise themselves, a bit superfluously, as her brothers. She also took part, at the Pergola, in a comic melodrama with music (22 March 1871) Il Califfo by Ettore Dechamps playing the slave, Amina, to the Haroun al Raschid of Pietro Silenzi.

In August 1871, she was back in England, singing at Rivière’s proms and in Manchester, for de Jong (‘a recall after each song’), before whisking back to Aix-la-Chapelle (‘Prima donna of the Covent Garden concerts’), Bordeaux, Lille, Baden (‘avalanche de bouquets’) under the management of Ullman, amid rumours of great things to come. And come they did. Mlle Fanny Rubini -- in demand for the Parisian concerts (Cherubini 'Ave Maria', 'O luce di', duets with Trebelli, Tagliafico)-- was engaged as a principal soprano at Paris’s Théâtre des Italiens.

She made her debut there singing Gilda in Rigoletto alongside delle Sedie, and was wholly successful: ‘[Elle] n'a qu'à se louer de l'accueil du public. Ses deux duos, l'un avec le ténor, l'autre avec le baryton, lui ont acquis les sympathies de l'auditoire. Sa voix de soprano est d'un beau timbre, surtout dans les cordes hautes, et sa méthode est excellente. Mais il ne faut pas qu'elle se lasse de travailler, ne fût-ce que pour donner plus de souplesse à son organe et pour mieux soigner ses attaques, qui parfois n'ont pas été très-exactes. Somme toute, elle peut être satisfaite de l'épreuve, et le succès doit l'encourager. On peut même dire que c'est à elle plus particulièrement que s'adressaient les applaudissements qui ont éclaté après le quatuor.’

It was rumoured that she would follow up in La Sonnambula (‘in which she played at the Pergola in Florence’) but she seems, later during her engagement, to have appeared only with Marietta Alboni, Gardoni and Penco, in the part of Elisetta in a few performances of Il matrimonio segreto where her singing pleased more than her acting (‘Mlle Rubini a lancé une pluie de perles de la plus belle eau et du plus beau son’, ‘Mlle Rubini fait ce qu’elle peut, mais son jeu laisse encore beaucoup à désirer’).

From Paris she headed back to London, where she and one of her brothers mounted a concert at the Hanover Square Rooms ('L'Estasi'), then to Baden for the concert season, singing alongside Csillag, delle Sedie and Campanini ('O luce di'), and to Italy or was it Warsaw where, it was said, she had been signed to appear in Mignon. ‘She is engaged for the season as prima donna assoluta at the Apollo Theatre, Rome’ reported the Paris music press.

Thereafter, she turns up Valletta in Malta (Dinorah), at the Fondo (Dinorah) and Mercadante (Rosa in La Campana dell'eremittegio, Principessa di Tesca in Golisciani's Wallerstein) in Naples, and for the summer of 1875, alongside Tamagno and Justine Macvitz, at the Liceu, Barcelona – now equipped with a new name. She has become Madame Rubini-Scalisi, the wife of conductor Carlo Scalisi.

In 1876 she visited South America, and in 1876-7, she can be seen sharing the billing with Erminia Borghi-Mamo and Elena Sanz at the Teatro Real, Madrid, performing La Sonnambula, Rigoletto, Linda di Chamonix, L'Étoile du Nord, Fra Diavolo and Dinorah, with Gayarre as her tenor and Mariano Padilla as baritone. With the last named, she scored ‘un trionfo’ as Linda: ‘la artista de las afligranadas fiorature, a que se presta se voz de siempre grate timbre, y con cuyos magnificos recursos tanto ha brilliado en Rigoletto, Sonnambula y Dinorah. In 1878 (27 November) she took the soprano role in Auteri Manzocchi’s Il Negriero (27 November 1878) alongside Stagno and Moriami. In June 1880, in Paris, she played in the Marquis Filiasi’s private production of Il Menestrello, and she also took part in several pieces composed by Bottesini, notably his Ero e Leandro and Cedar, programmed in 1880, at Naples, where she and her husband were engaged.

The Scalisis remained a considerable time at Naples and its San Carlo Theatre, where Carlo Scalisi, for a number of years in the 1880s, actually took over the management. Fanny, there, sang everything from Amelia in Simone Boccanegra to Elsa in Lohengrin,the title-role in Dinorah, Catherine in L’Etoile du nord, Gilda in Rigoletto, Sita in Le Roi de Lahore and Santuzza in Cavalleria rusticana.

Elsewhere, in the 1880s, I see Fanny singing Traviata at the Rome Apollo, Aida at Florence and at Nice, at the Carlo Fenice, Genoa in Les pêcheurs des perles, I see mention of her at Brescia, at Seville, Malaga, Granada, Turin and Brindisi, and in 1888, Scalisi having bankrupted at Naples the previous season, she spent several months back in London, once again teaming with Bottesini (‘applauded for the dramatic power she displayed in an aria from Nenia’), with Helen D’Alton and Isidore de Lara, in a series of concerts.

After London, however, I find little sign of Madame Scalisi -- although she seems to have tackled Santuzza in Foggia -- until, in 1893, it is announced that she and her husband will take up positions at the head of the singing department at the Naples Conservatoire. If Fanny did this, it was not for long. For, in 1894, I find her – with no sign of him – back in London, and back on the concert stage. The first occasion is a matinee musicale (‘nineteenth season’) given by one Signor Bonetti, and Madame Fanny Scalisi ‘from La Scala, Milan and the San Carlo, Naples’ is top-billed. La Scala? But the surprise comes further down the bill. ‘Madame Adelaide Rubini’. Fanny’s mother would have been over eighty years of age. Surely this cannot be she. Is it perhaps sister Adele taking up the family stage name? 25 July she has her own concert at Collard’s Rooms. The same Madame Adelaide appears again on 2 July 1895, when Fanny mounts her own concert at the Queen’s Hall. The previous week, she had appeared at the Music Trades prize-giving at the Agricultural Hall, as winner of the the piano section! The soprano award was won by … Miss Annie Rosa Swinfen. Oh no!

The Queen’s Hall concert is my last sighting of Fanny as a performer. Maybe she went back to Italy where, I think, I have seen her husband conducting in the early days of the new century. Ultimately, however, she did return to Britain, for the British records reveal the death of ‘Frances J Scalisi’, at the age of 68, in the district of Steyning (presumably at Hove) in 1915. She lies in Mill Lane Cemetery, in a sadly neglected grave ...

Mother Adele, who had spent her later life living with daughter Adele (Mrs Inderwick) and her family, in England, died in Brighton in 1903, at the age of 90.

As for the music-teacher brothers, Edward – as we know -- ended up in America, and he was never so famous as in death. In the 1870s he began teaching music in Exeter, where in 1883 he married a local girl, Mary Smith (d Surrey, 29 June 1918). From Exeter, Torquay, Tiverton, Taunton and Teignmouth, he moved to Malvern and tried teaching in Birmingham, before throwing it in and emigrating, in about 1890, to Ontario, and finally, in 1897, to America.

William made altogether more of a success in life, largely as a composer of light piano music which he published voluminously under the name G[uglielmo] Jervis Rubini. He, too, married and I spot him the 1891 census ‘aged 44’ with wife and baby boy, mother and sister, Adele Inderwick (d 1934) and child, before losing him. Apparently he died in 1895.

Fanny Scalisi did, herself, have at least one child. In 1927, the Grands Cercles of Paris include amongst their listings one ‘Jervis Arthur Scalisi’. This is presumably the Arthur George Jervis Scalisi, composer of ‘Najah’ (three Hindoo dances for piano) and ‘The Opium Dream’, the George Scalisi seen playing piano at Wigmore Hall, and above all the Arturo Domenico F G Scalisi born in Valetta, Malta, in 1874, and married in London in 1897. 'Captain Arthur George Scalisi-Jervis' of Bedford Chambers ... 'medical officer' ...

And here’s the rub. This Arthur Scalisi married, in what seems to have been a double wedding, a Miss Emily Mary Bowden. The other groom was one Luigi d’Antonio and the other bride was Miss Alice Edith Jervis, of Shenstone, Staffordshire, the daughter of the Hon Edward Swynfen Jervis of Little Aston Hall, and the legitimate descendant of that Lord St Vincent to whom, I was so sure, our Jervis family was only pretending to be related. Do I have now to infer otherwise?

Emily Mary Scalisi of the Palazzo Schioppa Riviera de Chiesa, Naples, wife of Arthur Scalisi, died 26 July 1897. Probate to Arthur Scalisi and ... Alice Edith d'Antonio, wife of Luigi d'Antonio ... effects: a whopping 29,000 pounds! After his momentary marriage, Arthur remarried and he died in Vancouver, Canada 10 February 1942.

Well, if there is a connection, the music in the family goes much further back than I had counted upon. To the famously colourful Mary Ann Jervis, pupil of Pasta, composer of the opera Siroe (1831), a selection from which was sung at Oury’s concert on 29 July of that year, the extravagant enchantress of the Duke of Wellington, sometime wife of the ‘mad’ Dyce Sombre, and later Lady Forester.

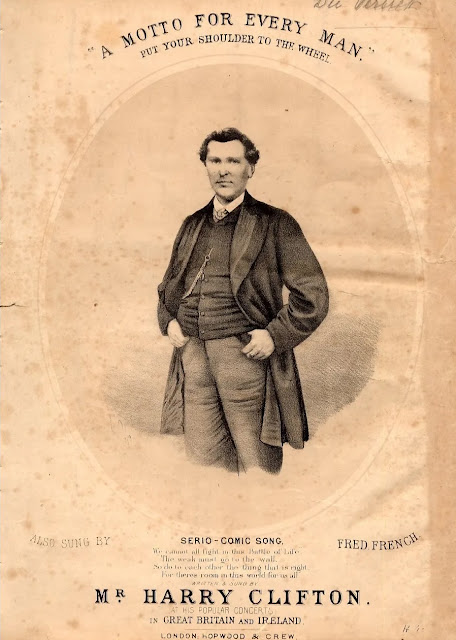

Guglielmo/William (not ‘George’ as the web would have it) published a piece of dance music in 1877. It is entitled ‘L’Étoile du chant’ and its title page bears a colour lithograph of Fanny as Zerlina in Fra Diavolo. Alas, search as I may, I can find no surviving copy. However, the National Portrait Gallery hold this photo of a 'Miss Rubini' which seems as if it might be the young Fanny ...

PS I discover that the singing Miss Swinfen (1863-1922), later Mrs Charles Burrell, was the daughter of a city missionary from Brixton … could that name really be a coincidence?